Cook Islands to Allow Seabed Mining Licenses Despite Negative Environmental Impact

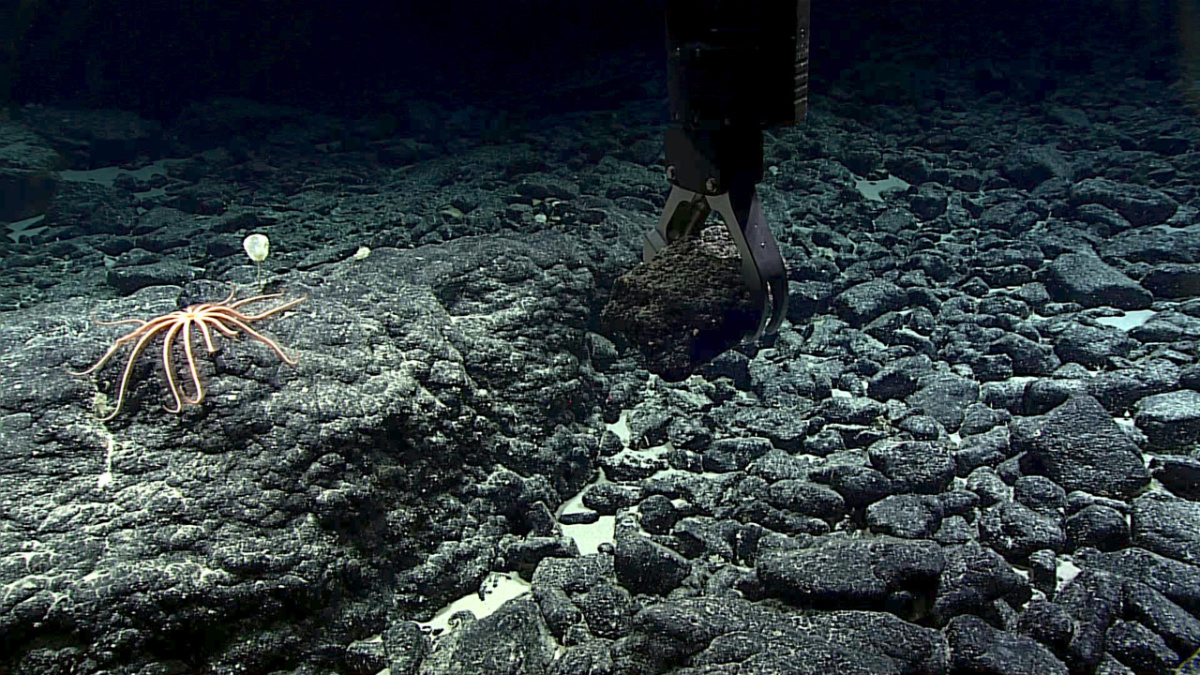

The ROV Deep Discoverer grabs a manganese-crusted rock sample near a brisingid sea star at about 7,900 feet during a 2017 expedition at Te Tukunga o Fakahotu dive site near the Cook Islands. NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin

By Monica Evans

The Cook Islands government plans to license seabed mining operators to prospect its exclusive economic zone for manganese and cobalt nodules within the coming financial year, Deputy Prime Minister Mark Brown told the Cook Islands News.

Brown’s comments, reported in a May 23 article, came in response to a new report commissioned by environmental advocacy groups The Ocean Foundation and MiningWatch Canada. The report warns of serious environmental impacts if mining takes place in the Pacific Ocean’s seabed, and says that even working out what those impacts might be will take a lot longer than the government’s projected timescale of commencing mining in less than five years.

“We’re talking about activities at depths of up to four kilometers,” or about 2.5 miles, the report’s lead researcher, Andrew Chin, a marine scientist at James Cook University in Australia, told Mongabay. “And trying to figure out how an ecosystem works takes a long time. I mean, people are still arguing about how mangroves work, and you can walk through them! So within five years, I just can’t see us being in a position to really understand what the impacts are going to be.”

Cook Islands seabed minerals commissioner Alex Herman said in an email to Mongabay that “commercial nodule recovery will have impacts on affected species and habitats in the deep sea,” and added that baseline studies, mitigation strategies and monitoring would all be important if mining were to go ahead. “The Government has to look at issues from a broader perspective,” she added. “This sometimes involves balancing conservation interests with sustainable development aspirations.”

Herman said those aspirations include creating new income streams because the country now earns almost 70% of its revenue from tourism. It has suffered greatly from coronavirus-related travel restrictions, despite itself not recording a single case of COVID-19. “The seabed minerals sector will provide economic diversity that is critical for the Cook Islands’ future as a nation and lessens its reliance on tourism,” Herman said. “The recent COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted our vulnerability, and the need to diversify.”

Mining a Marine Protected Area?

The Cook Islands made international news in 2017 when it turned its entire exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which spans nearly 2 million square kilometers (772,000 square miles), into the largest mixed-use marine protected area in the world. Dubbed “Marae Moana,” which means “sacred ocean” in Cook Islands Maori, the park was designed to ensure all activities within it complied with its overarching purpose: to protect and conserve the ecological, biodiversity, and heritage values of the country’s marine environment.

A decision-making council and a technical advisory group, both comprising government officials, traditional leaders and civil society organizations (CSOs), were established to help develop a new marine spatial plan that fit the objectives of Marae Moana, and to ensure that any new ocean-related initiatives comply with the park’s overarching purpose. The plan is still being developed.

But late last year, the government passed the Seabed Minerals Act 2019, which specifically allows the country’s Seabed Minerals Authority to bypass the Marae Moana Council and technical advisory group when designating areas for seabed minerals activities, and for this to occur before the marine spatial plan is in place.

“So they’re going to give out mining exploration permits for areas which may in fact be places that should be protected under Marae Moana,” Kelvin Passfield, director of the local conservation group Te Ipukarea Society, told Mongabay. The organization sits on the technical advisory group, but Passfield said the government has ignored its advice and that of other CSOs with marine conservation expertise, and that the advisory group had only met once in the past 12 months.

“Civil society have a role to play in advocating and raising awareness on issues,” Herman said when asked about the CSOs’ concerns. “But at the end of the day, Government needs to make often-hard decisions based on the best interests of our country and people.”

Known Unknowns

Te Ipukarea Society advocates that the Cook Islands endorse a 10-year moratorium on seabed mining that civil society leaders put forward at the Pacific Islands Forum in Tuvalu in August 2019 and that the governments of Fiji, Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea support. The idea is to allow sufficient time to conduct in-depth research on the ecosystems in question and potential mining impacts.

But the Cook Islands government has vocally opposed the moratorium. Marine scientist Jacqueline Evans, who directed the Marae Moana coordination office from 2017 to 2019, was fired last year after expressing support for the freeze in an internal email.

In a letter to the Cook Islands News on June 4, Deputy PM Brown said the government simply wants to gain the knowledge to determine whether or not mining could be conducted sustainably, and issuing exploration licenses is the only way to fund such research. “Without exploration (which I stress, is not ‘mining’), we have no realistic way of gaining a better understanding of the deep-sea environment, and indeed to know whether we may or may not be able to harness the resources which exist at these depths in the longer term,” he wrote.

Passfield said while the government claims all parties want the same thing — more information — “they have not demonstrated this in their actions.” Last year, it approved two short research cruises by different companies and “there was no requirement placed by Government on these cruises to collect any biological samples,” he said. “Only nodule and sediment samples were taken, and this was just for analysis for mineral content, nothing biological.”

Herman acknowledged the dearth of knowledge on the deep-sea environment, and said that should mining go ahead, the government would take a precautionary approach and adopt environmental management and mitigation strategies until further best practices can be determined. “The effectiveness of mitigation strategies to protect the environment will become known over time,” she said.

But Chin said it’s difficult to envisage how any mining could be carried out in Cook Islands’ waters without irreversible ecosystem impacts. “These are quite diverse habitats, and so many new species are still being discovered,” he said. “And we know that, generally speaking, because of the environment of high pressure, low light, low energy and low temperature, deep-sea animals grow slowly, and anything that grows slowly is quite vulnerable to an acute impact like mining.”

As the report outlines, lots of species, including corals, sponges, sea urchins, sea stars and jellyfish, live on the manganese nodules themselves, and many others rely on them. Deep-sea octopuses, for example, lay their eggs on dead sponges attached there. “So if you’re mining the nodules, you are removing everything that’s associated with them,” Chin said.

Beyond the seafloor, mining would likely also impact the whole water column right up to the surface, Chin added, both directly through plumes of sediment and tailings, and indirectly through ecological linkages. “So those impacts could be felt in things like tuna fisheries, which are extremely important for the Pacific,” he said.

Reposted with permission from Mongabay.

- Island of Tokelau Becomes World's First Solar-Powered Country ...

- New Database to Help World's Largest Marine Park - EcoWatch

- Race to Mine Deep Seabeds, With Unknown Ecological Impacts

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe