977,000 Shoes and 373,000 Toothbrushes Found Among 262 Tons of Plastic Debris on Remote Cocos Islands

Cocos Keeling Islands Islet Beach, Australian Territories, Australia. Mlenny / iStock / Getty Images Plus

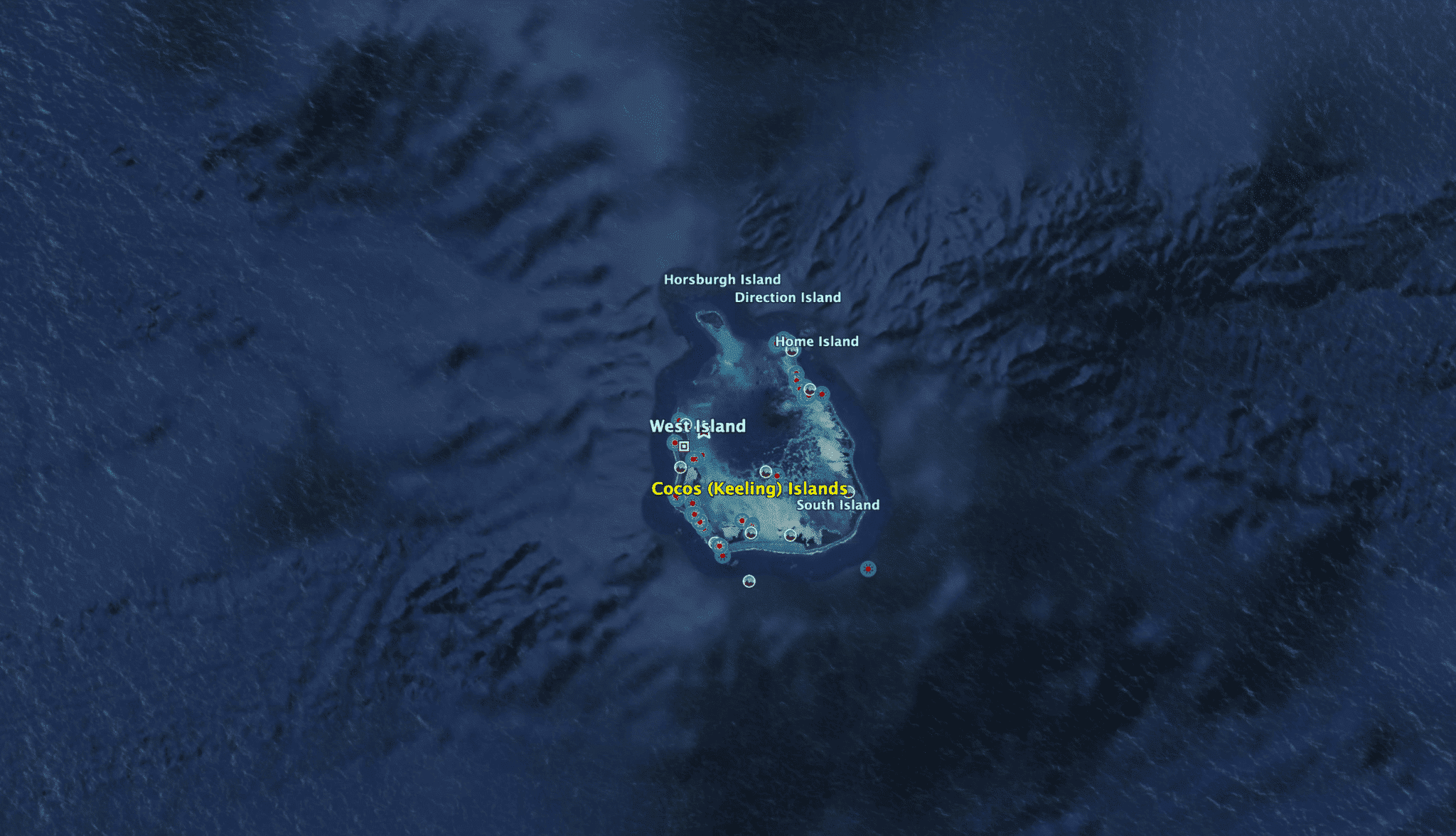

There are only around 600 people living on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the Indian Ocean. But their beaches are littered with 414 million pieces of plastic.

That’s the calculation of a paper published in Scientific Reports Thursday. Its findings suggest the world has “drastically underestimated” the plastic pollution problem, lead author from the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania Dr. Jennifer Lavers told BBC News.

“Islands such as these are like canaries in a coal mine and it’s increasingly urgent that we act on the warnings they are giving us,” Dr. Lavers said in an IMAS press release.

The plastic found by Lavers and her team weighed 238 tonnes (approximately 262 U.S. tons) and included 977,000 shoes, mostly flip-flops, and 373,000 toothbrushes. Lavers explained to NPR that remote islands like the Cocos are valuable places to study the circulation of ocean plastics, since their small population means the plastic that washes up on beaches comes from elsewhere and is not immediately cleaned up. Lavers has studied plastic on other isolated islands. In 2017 she found that Henderson Island in the Pacific had the highest density of plastic waste of anywhere on earth, the press release explained.

“You get to the point where you’re feeling that not much is going to surprise you anymore,” Lavers told NPR, “and then something does … and that something [on the Cocos Keeling Islands] was actually the amount of debris that was buried.”

In fact, 93 percent of the plastic Lavers’ team found was buried up to 10 centimeters (approximately four inches) in the sand, and 60 percent of the buried plastic were microplastics measuring two to five millimeters, the paper said.

“It’s the little stuff that’s perfectly bite-sized,” Lavers told NPR. “The stuff that fish and squid and birds and even turtles can eat.”

But while the buried microplastics pose a threat to wildlife, removing plastic buried that deep would require mechanical actions that would also disturb animals, BBC News reported. Ultimately, the solution lies in reducing the amount of plastic being produced and consumed in the first place and preventing any disposed plastic from entering the ocean, the report concluded.

Google Earth

But so far the problem is only getting worse, as report co-author of Victoria University Dr. Annett Finger explained in the press release. Around half of the plastic produced in the last 60 years was produced in the last 13, around 40 percent of plastics are disposed of the same year they are produced, and it is estimated that there are now 5.25 trillion pieces of the stuff in the ocean.

“The scale of the problem means cleaning up our oceans is currently not possible, and cleaning beaches once they are polluted with plastic is time consuming, costly, and needs to be regularly repeated as thousands of new pieces of plastic wash up each day,” Finger said.

The plastic tides are also a burden on the residents of the Cocos Islands, which are located around 1,300 miles off Australia’s northwest coast. It would take the local population 4,000 years to produce an amount of waste equal to what has washed up on their shores, The Guardian reported, and they have not been able to find a way to properly dispose of it.

Lavers said her estimates of the amount of waste on the islands were probably conservative, since the team did not dig below four inches and could not access some highly polluted beaches. They sampled seven of the 27 islands and multiplied the plastic count on certain sections of beach by the island chain’s total beach area.

Other researchers not involved with the study said they were not surprised by the results.

“It wasn’t a huge surprise to me, it’s simply that the surveys done up until now have looked at the surface and it’s obviously a lot of time and effort to dig deeper,” Dr. Chris Tuckett of the Marine Conservation Society told BBC News.

University of Toronto Ecologist Chelsea Rochman also said surprise wasn’t her primary emotion after reading the paper.

“It’s just kind of sad to kind of read about it and think, ‘Yep, OK, this is becoming, I guess, normal,'” she told NPR. “And we never wanted something like this to become normal.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe