Teacher to Heartland Institute: ‘We Don’t Do Alternative Facts in My Classroom!’

Twitter / @CityLightsUF

By Daisy Simmons

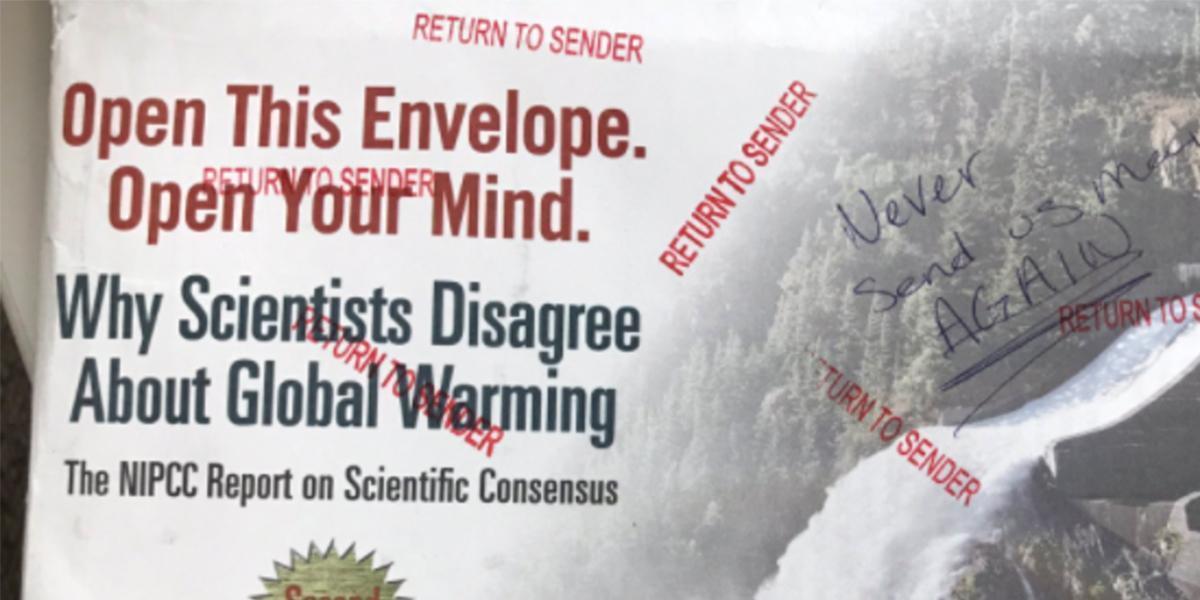

When Kelsey Singer, a student at Cedar Ridge High School in Round Rock, Texas, learned about a book her teacher had received in the mail—Why Scientists Disagree About Global Warming—she was perplexed and intrigued. Just who was responsible for what she considered to be a misinformation campaign?

So the college-bound senior created a website that investigates the “true nature” of the Heartland Institute, the Illinois-based organization responsible for the mailing. Her research, which went live on May 16, reflects Heartland’s ongoing efforts to discourage teaching of climate change, and the so-called “consensus” viewpoint on the scientific evidence, as a legitimate science curriculum topic.

This surely is not the first time Heartland has striven to conjure up climate science doubt where most climate scientists see little uncertainty. But this recent Heartland initiative may well reach a sizable portion of the nation’s primary and secondary school educators: PBS’ Frontline reports that some 200,000 K-through-12 U.S. teachers are slated to have received it by the end of 2017. The Heartland effort includes a well-designed book and a DVD. What’s more, the package is provided free of charge, not insignificant for teachers in the nation’s cash-strapped public schools.

https://twitter.com/EcoWatch/statuses/850836914555039746.” – Rick B., Cincinnati, Ohio;

• “All high school science teachers I know tossed that piece of crap straight into the recycling bin … I kept mine as an example of propaganda.” – Gerardo C., St. Louis, Missouri;

• “I recycled mine and sent an informative e-mail about it to the science teachers at my school. I also used their prepaid post card to write and tell them we don’t do alternative facts in my classroom!” – Chantal C., Ellittsville, Indiana;

• “Next, ‘why scientists disagree on the earth going around the sun.'” – Lloyd P., Atlanta, Georgia;

• “Got my copy and properly tore it into little pieces and gingerly sprinkled it over the recycling bin. Made a table top hovercraft out of the CD. Reduce, recycle, reuse and refuse! Love those four R’s!” – Debbie F., Greater Chicago, Illinois.

Still, some teachers are more susceptible to the book’s razzle-dazzle and its message than others.

Teachers still sending mixed messages about climate

As Sonya J. of St. Paul, Minnesota, wrote on Facebook, “It is hilarious reading, but also scary how many will fall for the slick look.”

A recent study justifies her concern, indicating that 30 percent of public school science teachers are teaching students that there is substantial disagreement among scientists about the causes of global warming.

These teachers could be more susceptible to such claims at a time when the president and many in his party in the Senate and House are dismissive of climate science.

“In some cases the Heartland materials may reinforce prejudices that teachers have who doubt or deny climate change. And it might induce people who are on the fence to teeter over,” said Branch. “The worry is that the people least likely to check its nature are the most likely to be influenced by them.”

Some of that susceptibility can be traced back to the absence of a clear climate science education pathway for teachers. Some senior-level science teachers may have gotten their teaching certificates long before climate science became as advanced as it now is.

Plus, it’s not just high school science teachers who are receiving the book, or who are discussing climate change in class. Freeman points out that a broad range of studies will touch on climate change organically, such as government and social studies classes and those dealing with language arts.

Teachers having had no refresher on climate science—or whose coursework never required it be learned in the first place—often are left to gather their information either from casual conversations or from random reports that haven’t been updated for a decade or more.

“In that case,” Freeman fears, “you might be more likely to embrace a book that says 2016 on it, and think, oh, this is up-to-date.”

Of course, there are also some teachers who flat-out reject climate science altogether. Colorado science teacher Cummings describes a staff meeting in which a junior high school teacher “dumped stuff on a table and said there’s no evidence of climate change.” And Freeman said at least half the people she encounters in her daily life, both in and out of work, don’t think “anthropomorphic climate change is a thing.”

Both share the belief that there’s no use trying to convince adults who are hard-wired not to accept the science.

But can you guess who they have found is open to empirical data? Students. And that’s why some teachers are turning the unscientific claims on their head.

Discussing evidence to empower students

“In my classroom, I know I change the minds of my students because they come preloaded with their parents’ conceptions,” said Freeman. “By the time I finish the unit, I would say 59 out of 60 students are ‘on board.'”

One of Freeman’s methods usually includes talking about rhetorical tactics. In fact, she said she received her copy of the book the same day that her class had been discussing how organizations, including Heartland, are often funded by powerful special interests to “weave this huge web of doubt about climate change.” And now, she’s got a current example.

“It actually helped me teach my students,” she said of the Heartland book. “And most of the teachers I talked to, what they were going to do was have kids go and look into the primary sources I pulled to argue against it … to use it as a way to further cement the fact that climate change is not controversial.”

A few teachers also posted about similar plans on Facebook, with Jeff W. of Utica, Michigan, and Kevin C. of Hazlet, New Jersey, among those mentioning they plan to use the Heartland materials to teach kids about vetting resources.

Using those materials as “teachable moments” may not be the ideal approach for every teacher, depending on their style, their class, and their community, said NCSE’s Branch. But he also points out that new research indicates that “inoculation” against climate misinformation could work much like a traditional vaccine.

“The idea is that if you expose students to climate change denial in a carefully controlled setting,” he said, “where you can make sure the problems associated with it are stressed and explained, then they’re better equipped to deal with it when they experience it outside the classroom, too.”

The academic focus on inoculation is fairly new, and there’s more to investigate. But informal observation shores up the idea that climate denial literature, when honestly considered, can often fall flat. One analysis of Reddit comments, for example, showed that a top reason people change their minds to accept climate science is that climate denial appears to be untrustworthy.

“I’m going to continue to use the book, to talk about it, and have it on hand as evidence—not evidence of a controversy, because that’s a façade,” said Freeman. “I don’t teach the controversy; I teach the corruption.”

The decision to not “teach the controversy” has worked well also for Cummings in Colorado Springs’s public charter school, called the Classical Academy, which she describes as “very conservative.”

“We turn the idea of a controversy on its head and instead teach the evidence; let the kids decide how they interpret the evidence,” she said. Her method: invite students to consider questions like, “Is climate change affecting Colorado?” Cummings said that when they look at signs like increasing wildfire, they usually decide that it is.

For Singer, the student who designed her own website, the potential of getting a good grade was a clear motivation. But she’s also hoping it will help inspire teachers and students to look at facts for themselves, and then draw their own conclusions.

Just that kind of objective thinking may result in an A for students—and for teachers standing up to climate misinformation. A Heartland Institute mass mailing to K-12 teachers has some educators rejecting the materials as non-scientific and unworthy of their classrooms.

Reposted with permission from our media associate Yale Climate Connections.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe