Hurricane Harvey, seen from the International Space Station. Elements of this image are furnished by NASA. Irina Dmitrienko / Alamy

By Daisy Dunne

When Hurricane Harvey struck Texas on Aug. 25, the state was hit by catastrophic flooding caused by record rainfall. In just three days, up to 40 inches (100 cm) of rain fell on Houston and its surrounding towns, leaving 80 dead and more than 100,000 homeless.

Now, scientists have calculated that those record rains were made at least three times more likely by climate change.

The analysis also shows that similarly extreme rainfall could become a further three times more likely to occur by the end of the century, even if global warming is limited to 2C.

If no efforts are made to stop the release of greenhouse gases, rainfall events on the same scale as Hurricane Harvey’s downpour could become up to 10 times more likely by 2100, the research found.

The research was conducted by scientists at the World Weather Attribution project, which aims to assess the role of climate change in recent extreme events, such as droughts, heatwaves and floods.

Human Influence

At 10 p.m. on Friday Aug. 25, the category 4 Hurricane Harvey made landfall near Corpus Christi on the southern coast of Texas. By Saturday, it had arrived in Houston, dumping close to 40 inches of rain by Monday morning.

As news coverage tracked the path of Harvey across Texas, much of the coverage began to question how climate change could have influenced the chances of such a disaster.

Three months on, the new analysis, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, attempts to address this question. It is what is known as a “single event attribution” study.

Single event attribution studies attempt to work out to what extent climate change could have influenced the likelihood of an extreme weather event, when other factors, such as natural climate variability, are also considered, explained lead author Dr. Geert Jan van Oldenborgh, from the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. He told Carbon Brief:

After an extreme weather event, we always get the question: “To what extent was this due to climate change?” The almost identical question that an extreme event attribution study answers is “How much has the probability of an event changed due to climate change?”

In this case, we looked at the probability in the current climate of getting as much rain as fell on Houston or more, and compared it with the probability a century ago, from observations and climate models.

Eyeing the Storm

To understand the influence of climate change on Hurricane Harvey, the researchers decided to focus on how warming could have influenced its record-breaking rains, rather than on how warming could have affected the chances of the hurricane forming, said van Oldenborgh:

We explicitly do not attribute tropical storms in this study, only the precipitation from all causes, among them tropical storms.

This is partly because it is more difficult to simulate the behavior of hurricanes in climate models than other extreme weather events, such as heat waves and extreme rainfall, van Oldenborgh explained:

The typical spatial extent of a heatwave is many hundreds of kilometers, so you can represent a heatwave with a climate model with a resolution of 200km or so. However, critical parts of tropical storms [hurricanes and typhoons] are much smaller, you only start getting realistic simulations with 25km resolution models. Only recently have the models and computer capacities increased enough, but even then the details of the dynamics of the storms are still not completely well-represented.

Instead, the researchers chose to focus their analysis on rainfall in Texas between Aug. 26 and 28, which caused most of the catastrophic flooding. For this analysis, the scientists collected rainfall readings from weather stations across the Gulf Coast.

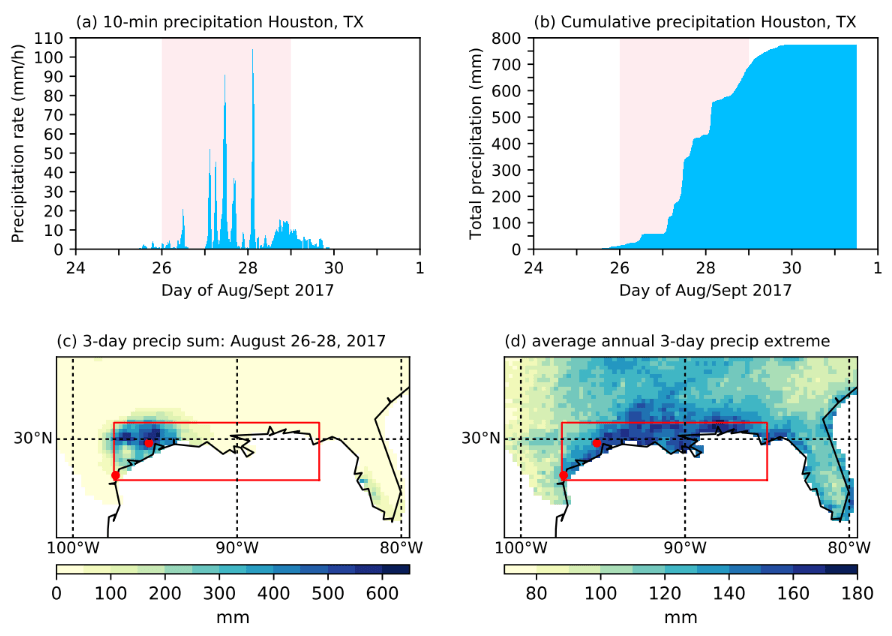

The charts below show the extent of these heavy rains over the three-day period. Chart A shows how the rate of rainfall in Houston changed over the three-day period, while chart B shows the total amount of rain that fell between Aug. 25 and 31.

Below this, chart C shows where the extreme rain was concentrated over the three-day period across the Gulf Coast, with dark blue representing high amounts of rain and yellow showing low. Chart D shows the spread of rainfall that is associated with annual average three-day maximum for the Gulf Coast.

van Oldenborgh et al. (2017)

A: The rate of rainfall over Houston from Aug. 26-28. B: Total amount of rainfall in Houston from Aug. 26-31. C: Spatial concentration of rainfall over the Gulf Coast from Aug. 26-28, with dark blue showing high rainfall and yellow showing low. D: Spread of rainfall that is associated with annual average three-day maximum for the Gulf Coast.

Human Fingerprint

To understand the influence of climate change on extreme rainfall, the researchers first compared their data to historical rainfall records dating back to the last century.

This allowed the researchers to work out how the likelihood of an extreme rainfall event has changed in the last 100 years and how often it would be expected to occur in the current climate.

The analysis shows that rainfall events as extreme as during Hurricane Harvey are expected to affect Houston once every 9,000 years, said study coauthor Dr. Karin van der Wiel, from the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. At the sidelines of the American Geophysical Union 2017 Fall Meeting, she told Carbon Brief:

[This event] was really, really rare. Locally, the return period was one in 9,000 years. Any city in the world would have flooded with that amount of rain. Regionally, for an event like this occur anywhere on the Gulf Coast, it was a one in a 100 year event, even that is quite extreme.

Next, the researchers compared their observations to the results of two climate models. For each model, the researchers ran two simulations: one assuming that there had been no climate change since the start of the industrial revolution and one assuming there had been moderate climate change since 1890.

Comparing the observations to the model results allowed the researchers to assess the extent to which climate change has made weather events such as Hurricane Harvey’s record rainfall more likely.

The analysis suggests that Hurricane Harvey’s downpour was made around three times more likely and 15 percent more intense by climate change.

The range of uncertainty around the results suggests that climate change made the event at least 1.5 times more likely and as much as five times more likely—and between 8 and 19 percent more intense.

This result is supported by a second independent study, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters on Dec. 12, which finds Harvey’s rainfall was made 3.5 times more likely by climate change.

The researchers also used the climate models to investigate how future global warming could affect the risk of extreme rainfall events by 2100.

The models show that, if future warming is limited to 2C, extreme rainfall events similar to Harvey could become another three times more likely by the end of the century.

However, if the world fails to cut its rate of greenhouse gas emissions, extreme rainfall events could become another 10 times more likely, and increase in intensity by up to 50 percent.

Global warming could raise the chances of extreme rainfall in a number of ways, including by increasing the maximum moisture content of the air, explained van der Wiel:

There’s many factors that have occurred in the climate system that made this event more likely to occur. So the sea surface temperature in the Gulf was extremely high, that was related to climate change. Atmospheric moisture is higher when it’s warmer, so the atmosphere can hold more water so when it rains, it rains harder.

Planning Ahead

The research explores how climate change is making extreme rainfall events more likely and more intense, but it does not investigate other factors that can impact urban flood risk, van Oldenborgh said.

For example, issues such as urban planning and water management can also play a role in vulnerability to extreme rainfall. Despite this, the findings should prompt policymakers to recommit to curbing climate change, he said:

The flood risks depend also on the other factors that we mention, such as water management and building practices. However, floods also depend on precipitation and we now know that the probability of extreme precipitation will increase as the world warms. By how much indeed strongly depends on how far we allow the earth to warm further.

The findings are “significant” because they offer “a rather detailed analysis” of how climate change could affect rainfall in the Gulf Coast, said Dr. Peter Stott, head of the Climate Monitoring and Attribution team at the Met Office, who was not involved in the study. He told Carbon Brief:

What I think is lacking in this study however is a specific analysis of hurricanes. The study does not examine hurricanes in the climate models, as to whether they have become either more intense or more frequent, and therefore the conclusions of this paper are rather general in scope regarding extreme rainfall, which can be caused by a variety of mechanisms in addition to hurricanes.

Further work is therefore needed to look at hurricanes in more detail in order to determine how the risk of impacts specifically associated with hurricanes has changed.

Reposted with permission from our media associate Carbon Brief.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe