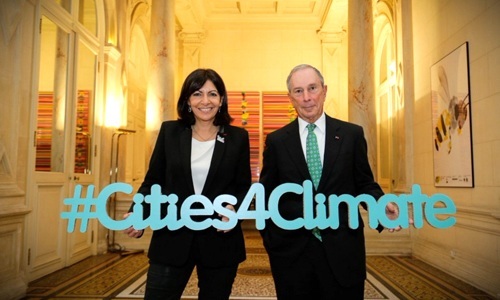

Welcome to #Cities4Climate – a historic event recognizing local climate action during #COP21 https://t.co/SQcYBll6JI pic.twitter.com/r8u5TDKVa0

— Mike Bloomberg (@MikeBloomberg) December 4, 2015

Cities, after all, already contain half the world’s population and are the source of 70 percent of its emissions. By 2040 their population share will be more than 70 percent and they will emit about 90 percent of all climate pollutants. So they clearly have to drive the solution. And because they are also the focus of the worst heat waves, the most damaging sea level rise and the biggest natural disaster burdens, they are powerfully motivated to curb climate disruption.

Finally, in a world where clean energy is suddenly cheap, the real conflict of interest is between fossil fuel producers (who want high prices for coal and oil as long as possible) and energy consumers, who want cheap, clean energy today if possible. And with few cities, the economies of the world’s big cities are tied to energy consumption, not fossil fuel production. So while oil and coal interests can tie down national governments and prevent them from decarbonizing quickly, cities want to get on with the job—and they are.

City governments don’t yet control all of their own emissions. But they do generally manage three sectors—buildings, transportation and waste—which are responsible for about 1/3 of urban climate pollution. A study by the Stockholm Institute found that by 2050 cities adopting economically profitable, emission reducing solutions in these three sectors could cut global emissions by 8 GT of CO2 a year—for comparison , the 2030 climate pledges currently on the table from all the world’s sovereign nations add up to Y GT. So the city capacity is very consequential. A study by the New Climate Economy also found that cities could save $17 trillion with these measures. Cities are also poised to save 1GT even before 2020—and early progress is the most valuable climate progress.

Overheard at the Climate Summit for Local Leaders earlier today #Cities4Climate #Quote pic.twitter.com/TFy6nef55E

— Cities4Climate (@Cities4Climate) December 4, 2015

Cities are already leading the day. The White House celebrated the collective work of more than 100 U.S. cities in their commitments to the Compact of Mayors, a coalition of cities pledging to undertake transparent, data-driven approaches to reduce city-level emissions, lower climate change risk and work to complement national and international efforts to protect our climate.

But cities can do far more if properly empowered. In the U.S., for example, some cities control the source of their electricity and where they do, they are moving rapidly to lower carbon sources. Omaha, Nebraska, owns its own power and has committed to cut its carbon emissions by 50 percent by 2030, far more than the 30 percent Obama Clean Power Plan target. In six U.S. states, including California, Illinois and Ohio, cities can choose their own electricity providers. So far 1,300 cities, with 5 percent of the U.S. population, have taken advantage of this, including such behemoths as Chicago and Cincinnati. And in every case the city gets cheaper power and cleaner, lower carbon electrons. U.S. cities are leading the way.

Electricity is not the only climate pollution source that cities need to be empowered to tackle. In many countries, cities are hampered by the lack of authority to issue bonds to pay for low carbon infrastructure like mass transit to building retrofits, even when such infrastructure is wildly profitable and would enable cities to cut taxes. Other cities in the emerging world have permission to borrow, but haven’t been given the necessary financial tools to qualify for a credit rating—so they can’t borrow affordably. Once Lima Peru got a credit rating, it built a rapid transit system that is transforming the face of the city.

Many cities lack the authority to insist that cars and trucks coming in burn clean fuels in clean engines—the resulting pollution problems not only disrupt the climate but also impose enormous health burdens on urban residents. Paris has been forced to consider banning diesel cars from the city, but has no influence over the lax, shoddy regulations that the member states in the European Union have established over vehicle emissions, as revealed in the last Volkswagen scandal. When Mike Bloomberg was Mayor of New York and tried to reduce traffic congestion and pollution in Manhattan with congestion pricing, the state legislature blocked him. And his efforts to encourage hybrid taxes in NYC’s yellow cab fleet were hampered by federal rules and regulations.

So the key to unlocking the full potential of city climate leadership is to empower cities with the policy levers to clean up not only buildings and transit, but electricity, fuels and vehicles—if every city had the strongest tools that are currently available only to a few, the world’s climate prospects would glow far more brightly.

Cities can lead. Cities want to lead. Let them!

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

What You Need to Know About Day 4 at COP21

Pledge Signed to Make All New Passenger Vehicles Zero Emissions by 2050

10 Cities Win C40 Award for Leading the Fight Against Climate Change

Least to Blame, Hardest Hit: Vulnerable Nations Show Leadership at COP21

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe