By Tony Iallonardo, Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families

Take a moment to think about what canned foods you use. True to my Italian-American roots, I consume a lot canned tomatoes, particularly in marinara, but I also like to make soups using canned stock as a base. After working with a coalition of six health non-profits to release a new report, I’m rethinking some of my favorite meals.

Modern canned foods have a chemical-based lining that is effective in reducing canned food being tainted with botulism. That’s good. But what those canned food makers use to make those linings is often not disclosed, and it may be toxic to our health. One chemical has been especially problematic in food products. It’s called Bisphenol A (BPA).

What is BPA?

You may have heard of BPA. Around four or five years ago the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned the chemical from being used in baby bottles and sippy cups. The BPA can migrate from can food linings into the food itself, where people then consume it and get exposed. The FDA cited strong evidence that BPA can effect hormone activity in people, and exposure has been linked to developmental problems in children, diabetes, breast and prostate cancer, erectile dysfunction and much more. As a result, the Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families coalition has put BPA on its list of Hazardous 100+ chemicals. So let’s just say it’s something you should avoid.

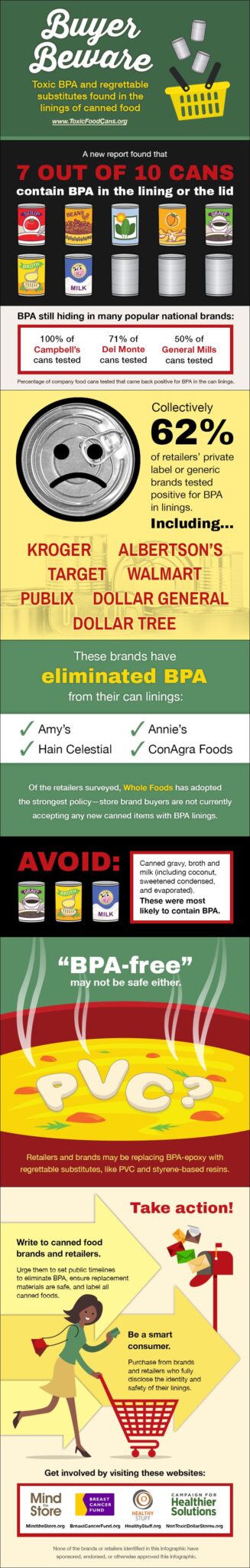

And here’s the rub. The new report tested almost 200 food cans from around the U.S., various types of food, retailers, and manufacturers that are household names like Campbell’s and Del Monte. We found BPA is common. It’s everywhere. Two-thirds of cans we tested had it. And it’s often not disclosed.

A Little More Bad News

Unfortunately, there’s some more troubling findings from the tests. Many of the other cans that didn’t have BPA contained other chemicals that are also problematic. Many of those other cans had acrylic resins that contain styrene, a chemical linked to cancer, or polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a plastic made with hazardous chemicals like the known human carcinogen vinyl chloride. The phrase the health groups use to describe this is “regrettable substitution,” meaning manufacturers swap out a toxic chemical, but then use another problem chemical in its place.

Making Safer Choices

The first thing to do is inform yourself. You can check out the report and results. When in doubt, avoid canned food if you can substitute with fresh food, or food packaged in jars and safer materials. There’s also safer cans! Amy’s Kitchen, Annie’s Homegrown, Hain Celestial Group and ConAgra have fully transitioned away from BPA.

Take Action

You can tell retailers you want safer canned food options. Retailers have significant leverage and pressure their suppliers to clean up their act. So advocates are asking the largest grocery chain in the U.S., Kroger, to phase out BPA in cans they sell under their brand. Click here to tell Kroger to eliminate and safely substitute BPA.

Watch Here

More Details

Still reading? Great, here’s a deeper look at the key findings.

- 100 percent of Campbell’s products sampled (15 of 15) contained BPA-based epoxy, while the company says they are making significant progress in its transition away from BPA.

- 71 percent of sample Del Monte cans (10 of 14) tested positive for BPA-based epoxy resins.

- 42 percent of sampled General Mills cans (six of 12, including Progresso and Green Giant) tested positive for BPA.

- Collectively, 62 percent of retailers’ private label or generic brand food cans analyzed in the study tested positive for BPA-based epoxy resins, including Albertsons (including Randalls and Safeway), Dollar General, Dollar Tree (including Family Dollar), Gordon Food Service, Kroger, Loblaws, Meijer, Publix, Target, Trader Joe’s, and Walmart.

- BPA was found in the majority of private-label canned goods tested at the two biggest dedicated grocery retailers in the United States: Kroger and Albertsons (Safeway). In private-label cans, 62 percent of the Kroger products sampled (13 out of 21), and 50 percent of the Albertsons products sampled (eight out of 16 from Albertsons, Randalls, Safeway) tested positive for BPA-based epoxy resins.

- BPA was found in private-label cans sold at both Target and Walmart, the largest grocery retailer in the United States. In their private label products, 100 percent of Target cans sampled (five out of five) and 88 percent of Walmart cans sampled (seven out of eight) tested positive for BPA-based epoxy resins.

- Discount retailers (commonly known as ‘dollar stores’) were among the laggards in transitioning away from BPA in can linings. Testing revealed that all (100 percent) of bean and tomato products tested from Dollar General, Dollar Tree and Family Dollar were coated with BPA-based epoxy resins, which is especially a problem because discount retailers are often the major retail outlet in low-income communities—which already face high levels of BPA exposure.

- Broth and gravy cans were the most likely (100 percent of those sampled) to contain BPA in the can linings; corn and peas were the least likely category (41 percent of those sampled).

- On the positive side, Amy’s Kitchen, Annie’s Homegrown (recently acquired by General Mills), Hain Celestial Group, and ConAgra have fully transitioned away from BPA and have disclosed the BPA alternatives they’re using. Eden Foods reported eliminating the use of BPA-based epoxy liners in 95 percent of its canned foods and stated that it is actively looking for alternatives. Whole Foods has adopted the strongest policy of the retailers surveyed in the report. Whole Foods reports that store brand buyers are not currently accepting any new canned items with BPA in the lining material.

Tony Iallonardo enjoys making pasta sauce, chili, soups and stews. He’s also communications director for Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families. A coalition of 450 health, labor, environment and business groups working to improve chemicals safety.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

7 Must-See Eco Docs at One of the Best Film Festivals in America

Monsanto’s Glyphosate Found in California Wines, Even Wines Made With Organic Grapes

Car Engine Cover, Fishing Net and Plastic Bucket Found in Stomachs of Dead Sperm Whales

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe