By Daisy Dunne and Tom Prater

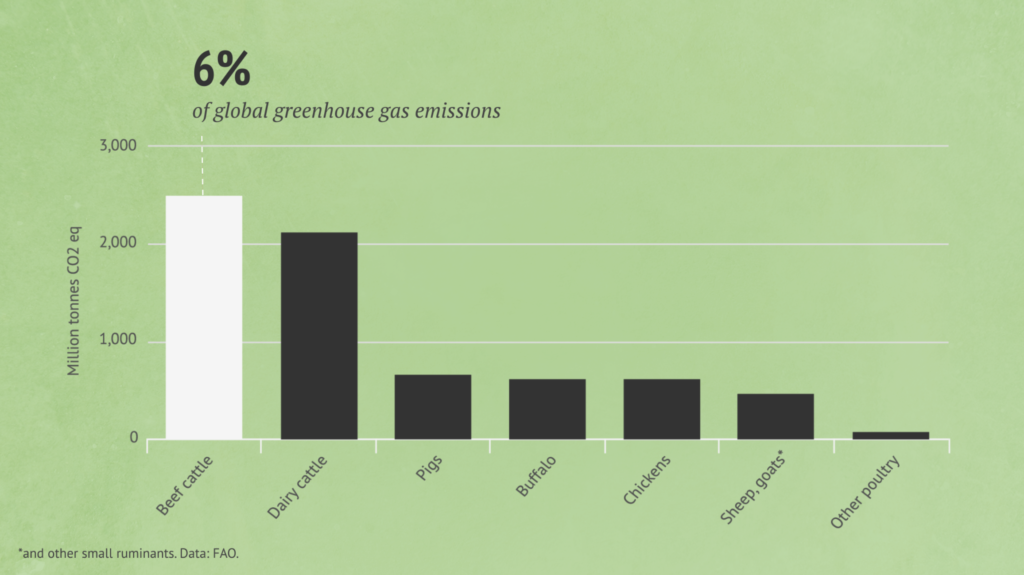

The beef industry is currently responsible for 6 percent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions, making it as large a polluter as the construction sector.

Eating less meat is one way to cut beef emissions. However, scientists have also started to look at ways that farmers can reduce the carbon footprint of beef before it reaches the plate.

Carbon Brief visited Rothamsted Research—a unique experimental farm in Devon—to find out more about how beef farmers could cut their contribution to climate change.

Making a Meal

The beef industry contributes to climate change in several ways.

Cows are ruminants, meaning that their stomachs contain specialized bacteria capable of digesting tough and fibrous material such as grass. The digestive process causes cows to belch out methane—a greenhouse gas that is around 25 times more potent at trapping heat than CO2.

Beef production is the leading cause of deforestation in many regions, accounting for 60 percent of forest loss across Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Indonesia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea in 2011. The removal of trees causes CO2 to be released into the atmosphere.

In addition, grazing cattle need plentiful supplies of grass—meaning farmers often use nitrogen fertilizer on their fields to stimulate plant growth. The production of nitrogen fertilizer causes the release of CO2 and the potent greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N2O).

In total, emissions from livestock account for around 14.5 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, with beef production accounting for just under half of this figure, according to the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO).

Carbon footprints of meat productionChart by Rosamund Pearce. Data source: FAO

Experimental Farm

In Devon, a county in south-west England, agricultural scientists at Rothamsted Research farm are exploring various avenues that could be taken to reduce this figure.

In a recent study, published in Journal of Cleaner Production, the researchers studied whether cow feed can influence the size of the animals’ carbon footprints.

The unique 60-hectare beef farm is akin to a giant scientific experiment, with researchers closely monitoring all of the “inputs” and “outputs” of the farm system.

The inputs include cow feed, while outputs include manure, the amount of weight gained by the animals and the run-off of nutrients, such as nitrogen. The region’s uniquely chalky soils prevent liquid from seeping into the earth—making it possible for the scientists to collect nutrient run-off using a network of pipes.

This close monitoring allows the researchers to keep a record of the carbon footprint of each animal reared on the farm, explained Graham McAuliffe, a Ph.D. student at the farm and the University of Bristol. He told Carbon Brief:

“Usually, when you calculate a carbon footprint, it’s based on an average statistic from either a herd, a regional level or a national level, but what we’re able to do here at the farm platform is to calculate that carbon footprint on a timescale—so, every two weeks—but also on an individual animal basis.”

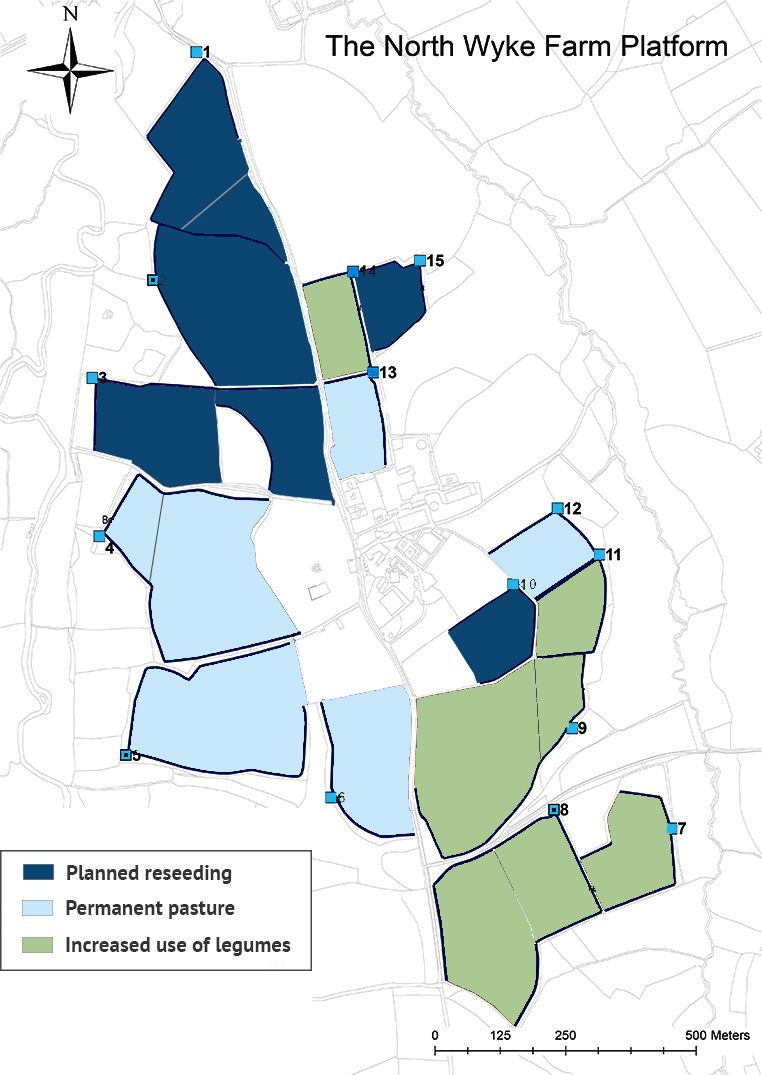

The farm is split into three equally sized plots, known as “farmlets.” The plots represent three typical farming systems used for beef production, McAuliffe said:

“Our first system is ‘permanent pasture’—which is, essentially, ‘business as usual.’ It doesn’t get reseeded, it doesn’t get ploughed and it gets conventional nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium fertilizer applications.

“Our second system is ‘white clover,’ which is a pseudo-organic system. Because clover has nitrogen-fixing nodes in its roots, we’re able to minimize or avoid inorganic nitrogen fertilizer on the soil.”

The third plot used is a pure grass system, which was also treated with nitrogen fertilizer, he added.

Bird’s-eye view of Rothamsted Research farm in Devon, showing three experimental pasture systemsMap by Tom Prater. Data source: McAuliffe et al. (2018)

Cow Countdown

For six years, the researchers collected data from cows grazing on each farmlet. Each autumn, 30 calves (Charolais x Hereford-Friesian breed) entered each farmlet at the point of weaning.

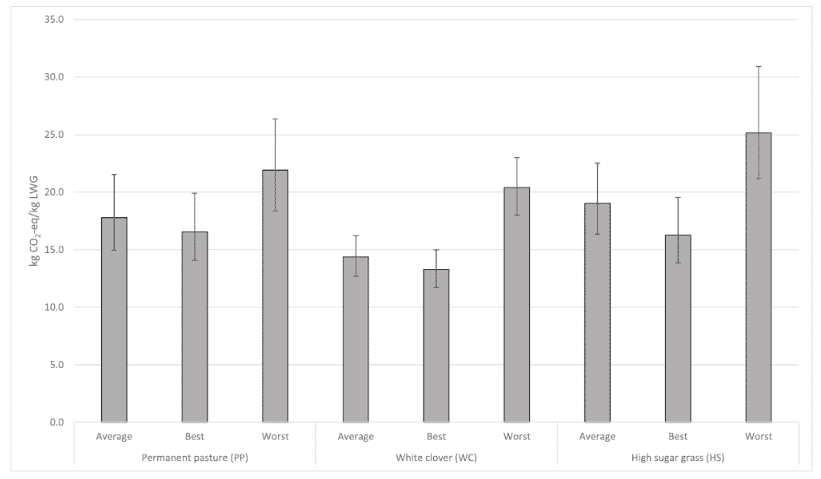

The chart below shows the carbon footprint (in CO2 equivalent) for the average cow grazed on the permanent (left), white clover (middle) and pure grass (right) plots. The chart also shows the carbon footprint of the “best” and “worst” performing animals on each farmlet.

Carbon footprints (CO2e) of the average, “best” and “worst” cows grazing on permanent pasture (left), white clover (middle) and pure grass (right)Source: McAuliffe et al. (2018)

The results show that cows fed on white clover tend to have the smallest carbon footprints, while cows from the permanent pasture and pure grass plots have the largest.

This is because the white clover system did not require the use of nitrogen fertilizer, McAuliffe said:

“The white clover system can have a lower carbon footprint because we don’t put nitrogen on it. That not only avoids the emissions associated with applying nitrogen fertilizer, but it also means that the upstream emissions from the production of nitrogen fertilizer are also avoided.”

However, even within each farmlet, some cows had larger carbon footprints than others, the results show.

The cows with the largest carbon footprints, known as “poor performers,” take longer to gain weight than others, McAuliffe said. Because of this, these cows must spend longer on the farm before they are sent to slaughter—meaning they spend more time emitting methane.

It is still not clear why some cows are lower performers than others, McAuliffe said. However, it is likely that genetics play a role in the differences between animals, he added:

“I would say a lot of it has to do with the environment, it has to do with genetics, it could be animal health—an animal might be poorly so it’s not consuming enough grass.”

Low-Carbon Cows

Following their results, the researchers plan to carry out an experiment to see if genetic selection could be used to produce cows with lower-than-average carbon footprints.

Selective breeding is a common technique in agriculture and involves breeding two animals with desirable characteristics (two cows with high milk yields, for example). If the trait has a genetic basis, there is a higher chance that the offspring will inherit it.

Though more research is needed, it is possible that breeding cows with a lower climate impact could help beef farmers to cut their emissions, McAuliffe said:

“If you’ve got a farm that’s got a lot of animals that are performing really poorly and replace them with animals that don’t require a lot of time on the farm to get to a finishing weight, I think it’s fair to say that the farm would be able to reduce its overall carbon footprint.”

Chewing the Fat

The findings offer promise for cutting emissions from beef production, said Dr. Tara Garnett, a scientist from the University of Oxford’s Food Climate Research Network, who was not involved in the study.

However, cutting emissions from beef production “can only take us so far,” she said. Last year, Garnett published a report finding that cutting down on global meat consumption would be the best way to tackle emissions. She told Carbon Brief:

“There are things to do on the production side to moderate greenhouse gas emissions from the farming sector, but they will only get you so far. High-consuming individuals and countries need to be cutting back on the amount of meat that they consume.”

Reposted with permission from our media associate Carbon Brief.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe