Scientists warn that a warm layer of salty

ocean water accumulating 50 meters beneath the Arctic‘s Canadian Basin could potentially melt the region’s sea-ice pack for much of the year if it reaches the surface.

The

findings were published Thursday in the journal Science Advances by researchers from Yale University and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

This “archived” heat is currently trapped under a surface layer of colder freshwater, but if the two layers mix, “there is enough heat to entirely melt the sea-ice pack that covers this region for most of the year,” lead author

Mary-Louise Timmermans, a professor of geology and geophysics at Yale University, told YaleNews.

The researchers discovered that the heat content of the warm, salty layer doubled from 200 to 400 million joules per square meter in the past 30 years.

The warming layer is “a ticking time bomb,” the study’s co-author John Toole of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution told

CBC.

“That heat isn’t going to go away,” he added. “Eventually … it’s going have to come up to the surface and it’s going to impact the ice.”

Scientists believe the warm water is coming from the Chukchi Sea in the south, where ice cover has been

rapidly melting and being exposed to the summer sun. Strong northerly winds are driving these warm waters north and flowing beneath the Canadian Basin.

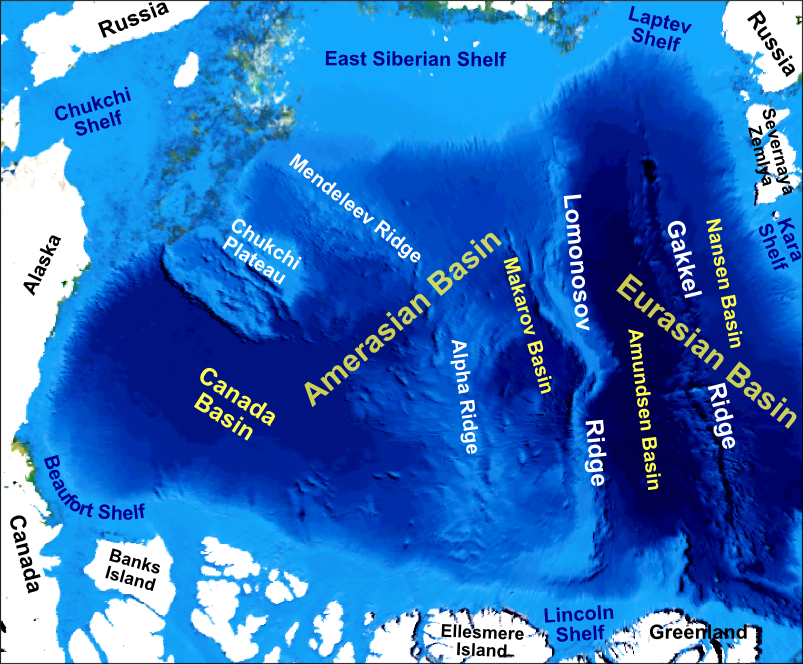

The Canadian Basin is a major basin of the Arctic Ocean that’s fed by waters from the North Chukchi Sea, just north of the Bering Strait between Alaska and Siberia.Mikenorton / Wikimedia Commons

“This means the effects of sea-ice loss are not limited to the ice-free regions themselves, but also lead to increased heat accumulation in the interior of the Arctic Ocean that can have climate effects well beyond the summer season,” Timmermans explained.

The Arctic is warming at a rate twice as fast as the rest of the globe due to climate change. Earlier this month, The Guardian reported that the Arctic’s thickest and oldest sea ice—also known as “the last ice area”—is breaking up for the first time on record. The breakage has opened up waters north of Greenland that are normally frozen-solid even in the peak of summer, a phenomenon that has been described as “scary.”

Ships have even begun to traverse across the melting Arctic. Such routes have been historically impossible or prohibitively expensive to cross.

“The last ice area" is breaking up for the first time on record. #climatechange https://t.co/sjvm72YaHG

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) August 21, 2018

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe