By Jamie Smith Hopkins

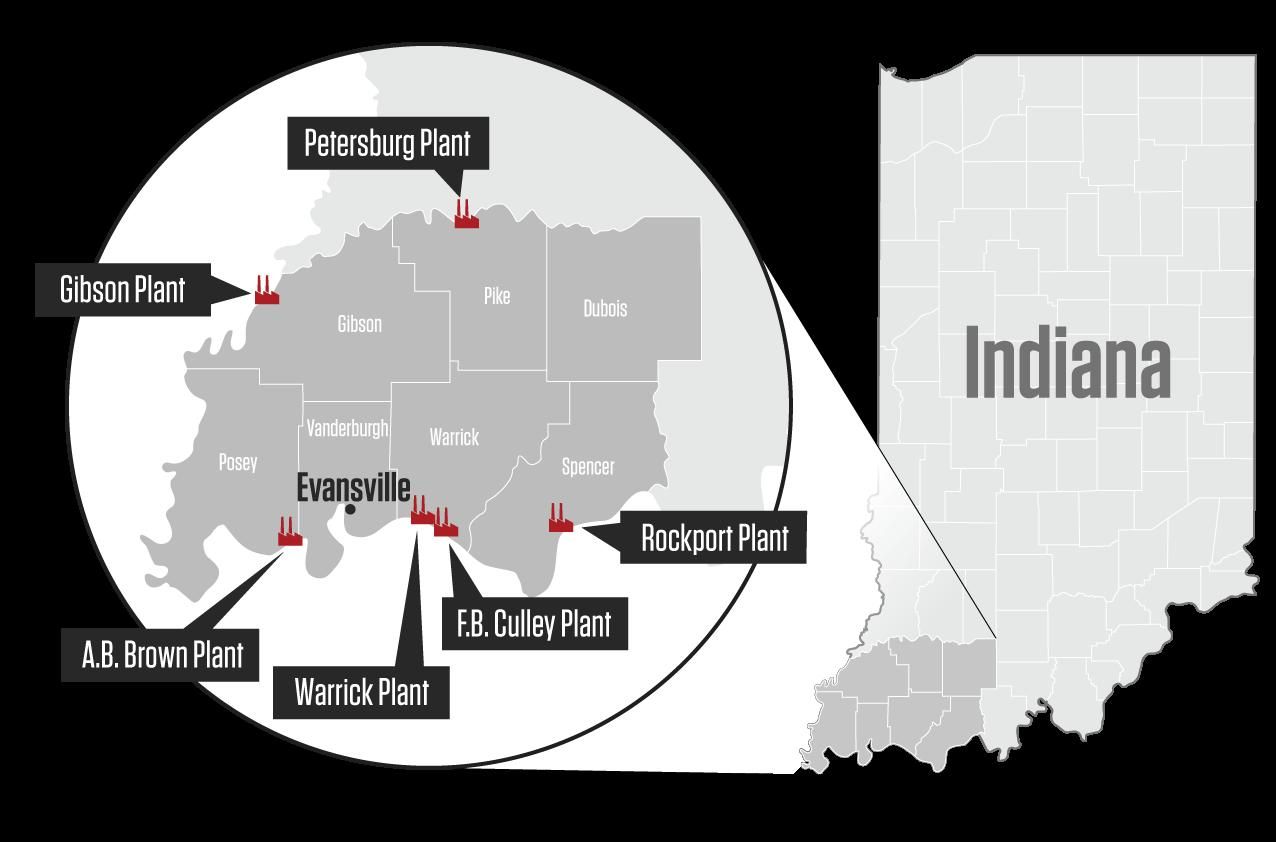

To see one of the country’s largest coal-fired power plants, head northwest from this Ohio River city. Or east, because there’s another in the region. In fact, nearly every direction you go will take you to a coal plant—seven within 30 miles.

Collectively, they pump out millions of pounds of toxic air pollution. They throw off greenhouse gases on par with Hong Kong or Sweden.

Industrial air pollution—bad for people’s health, bad for the planet—is strikingly concentrated in America among a small number of facilities like those in southwest Indiana, according to a 9-month Center for Public Integrity investigation.

The Center for Public Integrity, which merged two federal datasets to create an unprecedented picture of air emissions, found that a third of the toxic air releases in 2014 from power plants, factories and other facilities came from just 100 complexes out of more than 20,000 reporting to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). A third of the greenhouse-gas emissions reported by industrial sites came from just 100, too. Some academics have a name for them: super polluters.

Twenty-two sites appeared on both lists. They include ExxonMobil‘s massive refinery and petrochemical complex in Baytown, Texas, and a slew of coal-fired power plants, from FirstEnergy‘s Harrison in West Virginia to Conemaugh in Pennsylvania, owned by companies including NRG Energy and PSEG. Four are in a single region—southwest Indiana. Together, owners of these 22 sites reported profits in excess of $58 billion in 2014.

WOW: 20 Attorneys General Launch #Climate Fraud Investigation of #Exxon https://t.co/MB0JdliTxT @greenpeaceusa @350 pic.twitter.com/oTgEk9HIV6

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) March 30, 2016

Thomas O. McGarity, a law professor and regulatory scholar at the University of Texas at Austin, said the Center for Public Integrity’s findings show that “a lot of the problem is isolated, and what we need to do is focus in on these plants.”

The EPA says it’s doing that. In a written statement, the agency said its sustained emphasis on the electric power sector has led to “dramatically” lower emissions from power plants since 1990—”while the U.S. economy has continued to grow”—and it is working to get further improvements.

But not all the states are on board. Indiana is one of 27 suing the EPA over its Clean Power Plan, which would require reductions in climate-altering greenhouse-gas pollution from electric utilities. Indiana is also among the states that tried to block a federal rule to reduce emissions of dangerous metals and acid gases from coal- and oil-fired power plants. Its governor, Mike Pence—Donald Trump‘s running mate—is a pro-coal, climate change skeptic who says the costs of shifting to cleaner energy sources are too high.

Maintaining the status quo has costs as well: bad air that threatens health and fuels global warming. More toxic pollution from utility coal plants was sent into the air within 30 miles of Evansville than around any other mid-sized or large American city in 2014, a Center for Public Integrity analysis shows. That same 30-mile radius accounted for the most greenhouse gases released by U.S. coal plants that year around any city.

Across the country, the top 100 facilities releasing greenhouse gases—almost all of them coal plants—collectively added more than a billion metric tons to the atmosphere in 2014. That’s the equivalent of a year’s worth of such emissions from 219 million passenger vehicles—nearly twice as many as the total number registered nationwide.

The top 100 for toxic air emissions vented more than 270 million pounds of chemicals in 2014. The vast majority of these chemicals have known health risks, according to the EPA; they can target the lungs, the brain or other organs, and some can affect the development of children born and unborn.

Eight of the super polluters have closed. The rest, including all four in Indiana, still operate.

Tina Dearing, 48, from Huntingburg, Indiana, was unexpectedly widowed in March when her 57-year-old husband died of a heart attack. Coronary artery disease, the death certificate says. Two months later, researchers published the results of a 10-year study that showed why previous investigations kept finding shorter lifespans in areas with poorer air quality: pollution appears to accelerate harmful deposits in the arteries that cause nearly all heart attacks and most strokes.

Dearing’s family lives northeast of Evansville in a community within 30 miles of two of Indiana’s largest coal plants. She knows a variety of factors can play a role in an early death, but believes dirty air contributed in her husband’s case.

“The air quality stinks,” she said.

The Center for Public Integrity, which relied on the EPA’s most recent final Toxics Release Inventory data to track total chemical releases, found that the people who live within three miles of the top 100 polluters are in some ways a cross-section of America: spread across half the states, all races, young and old, in a wide range of income brackets.

But more of them are poor or African-American than the country as a whole, data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows. For instance, nearly 90 percent of the thousands living within three miles of ExxonMobil’s refinery and chemical plant in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, are black and about a third are below the poverty line. The complex, which ExxonMobil said has reduced total emissions over 40 percent since 1990, released more than 2.6 million pounds of chemicals to the air in 2014, including hydrogen cyanide—which can cause headaches, confusion and nausea—and known carcinogens such as benzene.

Mary B. Collins with the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry and two other researchers found similar disparities in a sophisticated analysis this year, writing that “there exists a class of hyper-polluters—the worst-of-the-worst—that disproportionately expose communities of color and low income populations to chemical releases.”

While people nearby are the most affected, these facilities can degrade air far afield. Almost all the states with top toxic-air emitters send a significant amount of pollution to downwind states, according to EPA analyses—in some cases reaching people hundreds of miles away.

Some of the companies that own the nation’s biggest polluters say their emissions break no rules and are simply a reflection of a facility’s size. Others point out that they’ve ratcheted down releases in recent years, including after 2014. FirstEnergy said it has shuttered coal plants accounting for more than 5,000 megawatts of power generation since 2012.

NRG, which owns or co-owns several coal plants on the top-100 lists, said its toxic air emissions are falling, including a sharp drop in mercury in 2015 to comply with new federal regulations, and it has set aggressive climate goals—a 50-percent cut in greenhouse gases by 2030, 90 percent by 2050—that would mean a major overhaul in the way it makes power.

Whole Foods Teams Up With SolarCity, NRG to Install Solar on 100 Stores https://t.co/fMSS2dQi8G @LatestSolarNews @SolarPowerWorld

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) March 10, 2016

“Things can’t continue on the same path as they have for decades,” Bruno Sarda, NRG’s chief sustainability officer, said of businesses worldwide. “More and more of our new revenue is coming from much lower-carbon sources.”

But coal is far from dead in America. And the tug-of-war over the future of electric power generation will affect everyone, some more than others. The influential utility industry. Blue-collar energy workers, from coal miners to solar panel installers. Neighbors of coal plants. Electricity customers. People suffering from the lengthening pollen season, dangerous heat waves, devastating floods and other effects of global warming.

To watch this unfold, come to one of the biggest coal-burning states, a place with no renewable energy requirements. No mandatory energy efficiency targets to cut back on unnecessary, money-wasting usage. No contingency plan for climate change repercussions, which so worried local university researchers that a group of them sent a letter to the governor last fall pleading with him to call on their expertise—a letter that went unanswered.

Come to Indiana.

Living and Dying in Evansville

Kavon Cooper’s asthma, his mother says, “was a constant battle.” If he spent too much time outside in Evansville, he needed medicine to breathe. If he went to a friend’s house, he never knew if he’d have to go home in a hurry. Sometimes his asthma attacks were so bad that he ended up in the hospital. So he stayed inside as much as possible with the windows closed, playing video games, dreaming of testing them for a living someday.

For all that, the 12-year-old seemed to be getting better. It was a shock when he collapsed and died at home last year, lying in the hallway by the bathroom as his nebulizer ran in his bedroom. The coroner ruled that he’d suffered an acute asthma attack.

His mother, Kris Dasch, 47, couldn’t understand what had happened. The only explanation she got was that pollen had spiked.

So had air pollution. But no one had told her that.

Levels of toxic specks called fine particles—typically formed by emissions from power plants, vehicles and factories—leapt up 20 micrograms per cubic meter the previous day, according to the air monitor less than a half-mile from the family’s home. They began to ease overnight, then jumped another 9 micrograms shortly before his death. Levels of sulfur dioxide, another common power plant pollutant, also rapidly increased at the same time that morning.

These are conditions that research suggests can trigger a severe, even deadly, lung reaction. No one had told Dasch that, either. No doctor had ever discussed air quality with her, other than the effects of pollen.

Dr. Carrie A. Redlich, director of the Yale Occupational and Environmental Medicine Program, suspects that’s almost always the case. Many physicians don’t think about the connection between air pollution and health, Redlich said. They might not know, for example, that research suggests tainted air and allergens such as pollen work like a one-two punch—together, the reaction is worse.

That both spiked in the lead-up to Kavon’s death makes them sound to Redlich like contributing factors. “That is an important interaction,” she said.

Now that air quality is on her mind, Dasch makes connections that didn’t stick out before. How well Kavon did on the rare occasions he took a trip outside the region. How a neighbor mentioned that her son’s asthma didn’t bother him as much when they lived in Arizona. How “there’s a lot of illness, a lot of sickness in this area.”

Vanderburgh County, which includes Evansville, has lower life expectancy compared with peer counties across the country and a higher rate of adults reporting fair-to-poor health, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Community Health Status Indicators. Some key influencers—poverty, unemployment and obesity—are actually better here than in most peer counties. What’s counterbalancing it are higher rates of smoking and air pollution.

Researchers already knew that poor air quality impairs children’s lung development, but studies in the past few years have also suggested multiple in utero complications such as autism spectrum disorder, found a possible connection with childhood psychiatric conditions and linked exposure to damage that can trigger neurological problems in old age. In 2013, the World Health Organization declared that air pollution causes cancer. Inflammation kicked off by the pollutants seems to be the common denominator.

“You add air pollution together with a lot of smokers, you are adding a lot of disease, premature death and costs that the state of Indiana incurs,” said Dr. Stephen Jay, a pulmonologist and emeritus professor of public health at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis who has pressed for a shift to clean energy.

Lori Salma, a preschool teacher from Evansville, says she is struck by the number of young children using lung medication. She and her 14-year-old son both have asthma, and there are days “when I feel winded after being outside for longer than 15 minutes.”

She’s frustrated that for all they’ve done in their house to try to reduce flare-ups—no carpets, no curtains, no pets and, of course, no smoking—”there’s nothing we can do to control the air that we breathe.”

Tina Dearing said her late husband, Vincent, would come home to Huntingburg from business trips and complain that inhaling the local air felt like someone standing on his chest. Her oldest daughter had trouble breathing as an infant. And she wonders whether the air contributed to her daughter’s daughter, now 2, being born so small—not preterm, but just 5 1/2 pounds. (Research suggests that air pollution can decrease birth weight.)

“That’s why we limit our time outside,” Dearing said.

Rose Hoffman and her family lived in a community near Dearing’s for years before moving in 2012 to Champaign, Illinois. Air quality was not the reason—in fact, when she occasionally heard bad news about it, “I didn’t want to believe it because we enjoyed living there so very much.” But what happened after they left, she said, “was stunning.”

Her nighttime wheezing stopped. Her youngest daughter no longer coughs at bedtime. The awful migraines besetting two of her children went away almost entirely and hers eased. Her husband, a doctor, saw his asthma symptoms improve.

Hoffman, 45, had assumed genetics, or being the child of smokers, explained her severe lung damage following a bout with pneumonia in Indiana — her doctors had no idea why it happened. Now, she can’t help but think that air could have played a role in that, too.

The State of the Air

Southwest Indiana doesn’t look like an industry stronghold. Evansville, population 120,000, is the biggest city by far amid the rippling farmland. Rural Kentucky is just across the Ohio River, while the state capital of Indianapolis—and the massive steelmaking complexes in northern Indiana—are hours and a world away.

But this is coal country, where the state’s 6,500 mining jobs are concentrated. Six coal plants operate here: Gibson, Rockport, Petersburg, Warrick, A.B. Brown and F.B. Culley, all but one within 30 miles of Evansville, which is also near two coal plants in Kentucky. A large piece of southwest Indiana power travels on transmission lines to be used elsewhere because the plants make more than 40 percent of the state’s electricity in an area with just 6 percent of its people.

They also make a disproportionate share of the pollution. The plants accounted for a quarter of Indiana air emissions reported to the EPA’s toxics inventory in 2014, a remarkable concentration in the most manufacturing-intensive state in the nation. Within the seven most southwestern counties here, three-quarters of the air pollution recorded in the inventory came from the six coal plants. And that doesn’t count the effects of the Kentucky plants.

Ask Mark Maassel about the air and he’ll recount the billions of dollars in environmental controls his members have installed over the last decade, some required by federal rules, some by EPA enforcement actions. He’s president of the Indiana Energy Association, a trade group for investor-owned utilities, and he sees “very significant changes and improvements in the environment of the state.”

Power plants’ sulfur dioxide emissions dropped 64 percent statewide between 2000 and 2014, he said. Nitrogen dioxide, which harms the lungs and contributes to ozone, often called smog, fell 69 percent, he said. As some coal plants shut down, carbon dioxide—which warms the atmosphere—also declined.

That’s meant cleaner air. Evansville-area concentrations of fine particles dropped nearly 30 percent over the past decade, EPA monitoring figures show.

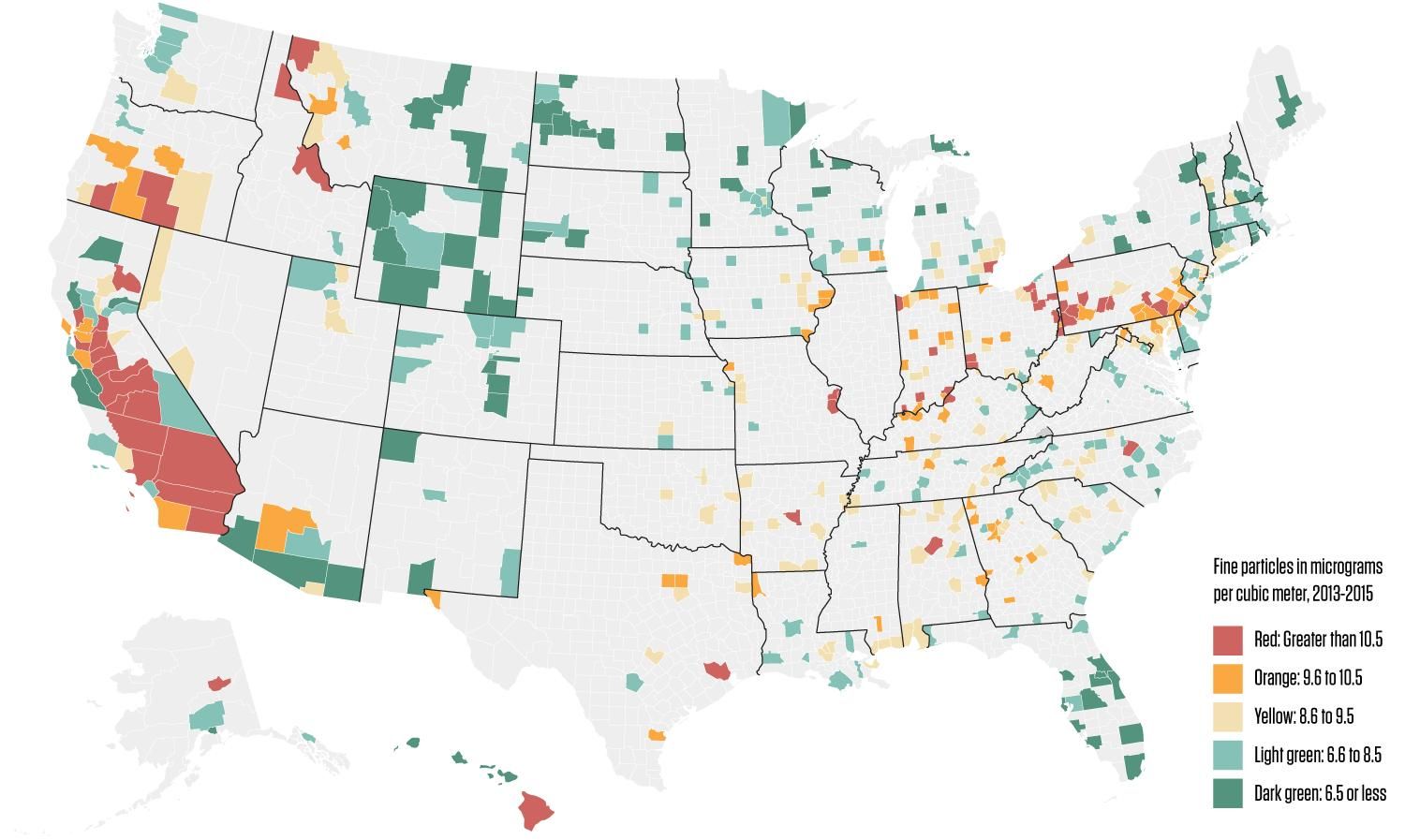

But the air here is still worse than in most of the country.

Vanderburgh County had higher levels of fine particles than nearly 90 percent of the U.S. counties with air monitors from 2013 to 2015, EPA records of average annual concentrations show. Vanderburgh was nearly on par with Manhattan, even though that New York City borough has nine times as many people and a lot more particle-spewing vehicles.

Despite that—and despite some power plants here running afoul of EPA rules in recent years, including for sulfur dioxide—the region isn’t violating federal air-quality standards for fine particles.

“The good news is, as of today, the entire monitoring network within the southwest Indiana area does demonstrate compliance,” said Scott Deloney, air programs branch chief at the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

The bad news: The standard for particles is based on total amount, but research is finding they aren’t equally unhealthy. The most toxic ones, a 2015 study by 11 researchers in the U.S. and Canada suggested, come from burning coal.

What’s more, researchers keep finding harm from fine particles at levels below the standard, which the EPA is reviewing to determine if it’s still appropriate. A new study led by a Johns Hopkins University researcher that focused on Boston—with markedly better particle levels than Evansville—found an association between that air pollutant and intrauterine inflammation, a key risk factor for premature birth.

In March, a New York University study estimated the share of premature births that can be attributed to fine particles. Indiana was second-highest in the country.

Premature birth can have lifelong consequences for children and is the biggest cause of infant mortality—a challenge for Indiana, tied for ninth-worst on infant death among U.S. states. Some studies have specifically linked air pollution to infant death rates.

Dr. Edward McCabe, chief medical officer at the infant-focused March of Dimes, says the evidence of pregnancy harms is now substantial enough that action—not simply further study—is required: “We need to do something about it.”

But Indiana officials, focused on more widely understood risk factors such as smoking, which the state has high rates of, haven’t delved into pollution as a possible contributor. A 2014 state report aimed at improving infant survival rates didn’t mention air quality at all.

Asked about it, Indiana State Department of Health spokeswoman Jennifer O’Malley said by email that “outdoor air quality is beyond the scope of ISDH and was not a consideration” in its infant-mortality work. She referred questions to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, which said it has no public-health specialists on staff.

Dr. Norma Kreilein, a pediatrician in southwest Indiana who has tried to draw attention to environmental-health problems she sees in the region, is fed up with the state.

“They’ve refused to connect pollution to public health,” Kreilein said.

A spokeswoman for Pence did not answer questions about the matter or anything else for this story, except for one asking for his perspective on coal.

“This abundant Hoosier resource supports over 26,000 Hoosier jobs and has historically provided Indiana’s economy with competitive electricity prices,” the spokeswoman, Kara Brooks, said by email. “Unfortunately, President Obama’s Clean Power Plan will drive up electricity prices, threaten electricity reliability, and put coal miners out of work. That is bad for Indiana and bad for America.”

Pro-Coal State

As Pence himself put it last year, Indiana is a “proud pro-coal state,” and its energy use reflects that. It relies on coal for 75 percent of its electricity, at a time when the national average has fallen to 33 percent.

Pence gave up his shot at re-election this fall to run with Trump in the presidential election. The Democrat in the governor’s race? A former coal lobbyist.

Pence’s popular Republican predecessor also was pro-coal, and supported a coal-gasification power plant project that went way over budget. But former Gov. Mitch Daniels’ administration also started a mandatory energy efficiency program to cut back on waste and crafted rules to allow more people to go solar.

The efficiency program is gone now, replaced with a law that sets no reduction targets for utilities and has saved less energy, according to the Midwest Energy Efficiency Alliance. State lawmakers tried last year to allow utilities to raise costs for customers with solar panels, stepping back only after they were flooded with complaints—solar advocates fear another attempt will come. And then there’s Indiana’s challenge with other states to the Clean Power Plan, now under a U.S. Supreme Court stay as a lower court considers the arguments.

This One Chart Says It All for the Future of Solar Energy https://t.co/jdNaJOaRc0 via @ecowatch #YEARSsolutions pic.twitter.com/MiNztFSJr8

— The YEARS Project (@YEARSofLIVING) June 5, 2016

That hasn’t kept change from happening, because national forces pressuring coal—cheap natural gas, falling costs for renewables, federal pollution rules—are here, too. As recently as 2009, more than 90 percent of Indiana’s electricity was coal-fired.

But if a complete energy transformation is inevitable, as some in Indiana assume, getting there quickly is not. There’s so much farther to go here than in most places.

Just a handful of states get a larger share of their electricity from coal, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration figures, and none is as populous as Indiana. The only place that burns more tons of coal for power is Texas, which makes four times the electricity and gets a lot of it from natural gas.

Indiana made 16 percent of its electricity from natural gas last year. That fuel’s unhealthy air emissions when burned are sharply lower than coal’s. (Natural-gas power plants aren’t tracked by the Toxics Release Inventory, which exempts certain operations from otherwise fairly broad coverage.) Gas plants also release 40 to 50 percent less greenhouse gases than equally sized coal plants, though that doesn’t include potent methane leaks before the fuel arrives on site.

https://twitter.com/FrackAction/statuses/745275505109139456 controls … makes sense,” Maassel said.

This reasoning galls Kerwin Olson. He’s executive director of the Citizens Action Coalition, an Indianapolis consumer and environmental advocacy organization that often clashes with utilities. Olson contends that the most cost-effective option is to stop using coal sooner, not later.

He’s not talking about health and climate costs, though research suggests they make the true price of coal much higher. He means people’s actual utility bills.

“If you’re a utility company with a guaranteed rate of return and the more you spend, the more you make, you’re going to choose the most expensive option,” he said. “That’s why we continue to rely almost exclusively on coal.”

Olson said that while coal-plant pollution controls were once the cheapest option, that’s no longer the case. Efficiency and wind aren’t only cleaner but are also less expensive than coal, he said, while utility-scale solar is on par.

That’s clearly the case for new construction. Comparing piecemeal coal-plant retrofits to the alternatives is trickier, but David Schlissel with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, which advocates for reduced dependence on fossil fuels, said many coal plants are uneconomic even without additional controls.

Cheaper electricity from gas and renewables prevents them from selling as much to the grid as they once did. In states such as Indiana where utilities own the plants, he said, ratepayers take the hit.

Utility analyst Paul Patterson said power companies aren’t necessarily wedded to coal—some are moving aggressively on renewables. But it’s an industry that craves stability, said Patterson, with New York-based Glenrock Associates.

And in states that have staked out pro-coal positions, he said, “there may be a whole variety of political issues” at play. AEP tells investors in its most recent annual report that it wants to rely more on natural gas, energy efficiency and renewables “where there is regulatory support.”

‘Beyond Coal’ in Coal Country

In southwest Indiana, a future without coal would unpredictably reorder industries and people’s lives. Most of the state’s 6,500 mining jobs are here. They’re a small piece of the region’s employment—about 2 percent—but their reach is widened by the truck drivers, suppliers and others whose jobs depend on coal. Mining—like utilities—also provides some of the best-paying work. Property taxes from the power plant owners boost small-town budgets.

At the United Mine Workers of America’s old union hall in Boonville, 30 minutes from Evansville, a half-dozen retired coal miners gathered in June to talk about their anxieties—in particular their frustration that Congress had yet to vote on health and pension benefits endangered in the wake of coal-company bankruptcies. Some of the politicians loudly proclaiming themselves pro-coal are not beloved here.

All of these men worked at a Boonville surface mine that supplied a local coal plant and shut down in 1998, its closure blamed in part on the Clean Air Act amendments of 1990. Marvin Bruner, who worked there 31 years, had to retire early and accept a smaller pension. Randal Underhill had to travel all over on construction jobs for power plants, living out of motels. David Hadley had to work in Indianapolis during the week and come home to his family on weekends.

But in this group, opinions of air-pollution regulation are nuanced. They’ve seen coal companies open new mines in the area since the Clean Air Act amendments—non-union ones. Bil Musgrave, 60, who contracted a rare bile-duct cancer he links to working amid hazardous waste dumped in the Boonville mine, is a Sierra Club member.

He feels the tension between the benefits and problems coal brings. You can’t be a miner without it, and yet Musgrave knows it’s burned to make far more electricity than his region needs. The Toxics Release Inventory figures for a nearby coal plant, he said, show “an enormous amount of pollution.”

Hadley, co-chair of the United Mine Workers’ Indiana political action committee and a former state utility regulatory commissioner, wishes the industry had pushed full speed ahead on clean-technology innovations 15 years ago. What if carbon capture were economically viable and widely used today? What good does switching to natural gas do, he says, if it doesn’t solve the carbon problem?

Hadley fears coal’s window of opportunity is all but closed. That would leave transition away from it as the only option—”a transition with consequences.”

Wendy Bredhold, a local Sierra Club representative, is a former Evansville city councilwoman who thinks about economic consequences, too. As the nation increasingly turns to renewables and big companies demand them, what will that mean for local growth prospects? Wouldn’t coal workers do better, she says, if state officials helped people with the transition instead of fighting it?

The Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign has notched successes across the country, preventing new plants from opening and convincing regulators that old plants weren’t cost effective and should close. An Indianapolis coal plant it targeted switched to natural gas this year.

Now the group is campaigning in Evansville, trying to do this work in an area where, as Bredhold puts it, “coal runs generations deep.” An Evansville event the Sierra Club organized this month drew 100 people but also attracted angry Facebook comments.

Bredhold sees health problems and the accelerating effects of climate change, and doesn’t think she can afford to fail.

“We can’t wait until these plants just can’t run anymore,” she said. “I want this transition to be as easy as it can be for my community, but it’s one that has to happen.”

Secondhand Pollution

The Cessna four-seater raced down a runway in Fort Meade, Maryland, loaded with equipment to measure ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide and greenhouse gases. For more than two decades, the Maryland Department of the Environment has tracked where pollutants come from. Agency scientists and university researchers have worked together to prove that other states routinely send unwanted contributions their way.

This isn’t academic. Pollution drifting over state lines complicates local efforts to clean the air.

Indiana—280 miles from Maryland at its nearest point—is one of the culprits, according to both Maryland and EPA analyses.

Closer states have a bigger impact on Maryland, but the reach of Indiana’s pollutants is impressive. An EPA analysis for a 2011 rule to reduce power-plant emissions that exacerbate interstate problems with fine particles and ozone showed Indiana significantly contributing to air pollution in 11 states as far northeast as Connecticut. Only Kentucky topped that, at 12.

Traveling pollution is why nine East Coast states petitioned the EPA in 2013 to make nine other states—Indiana among them—do more on ozone. That petition is pending; some officials told the EPA this year that they plan to sue to force a decision.

Indiana and the other targeted states, in a 2014 letter to the EPA, said they’ve made “tremendous progress” on air quality and the petition’s arguments are out of date.

Dave Foerter, executive director of the Ozone Transport Commission, which advises the EPA on interstate smog problems, said meteorological conditions made for better years in 2013 and 2014. But generally, the wind blows Midwestern pollution to the Northeast, and that problem continues, he said.

“Indiana tends to throw emissions a long way,” Foerter said.

That’s less likely to come from its cars than its power plants, because the plants’ smokestacks give pollutants the height they need to travel, according to Maryland regulators. New York, analyzing 2015 power plant releases, discovered that Indiana put out four times as much nitrogen oxides—a key ozone ingredient—for every megawatt-hour of electricity as New York did.

The Maryland Department of the Environment’s Tad Aburn isn’t suggesting car-heavy Maryland doesn’t make its own pollution. It does, affecting three other states, according to the EPA’s analysis. But Maryland’s power-plant rules are stricter than federal ones, and Aburn says the agency’s detective work shows the air improves when states work together.

“We need to do more,” he said.

The Climate In Indiana

Climate change, like air pollution, requires group efforts to combat. But in Indiana—where industrial greenhouse gas emissions are second only to Texas in the U.S. and exceed those from Israel, Greece and 185 other countries—the official position is inertia.

Pence once called climate change a “myth” and now positions himself as a skeptic: “I think the science is very mixed on the subject,” he told MSNBC in 2009, an assertion he repeated until he said on the campaign trail this week that human activities have “some impact” on climate. Not only is his state suing over the Clean Power Plan, but he also vowed that Indiana won’t strategize to reduce greenhouse gases even if the rule does take effect. He’s an enthusiastic supporter of the American Legislative Exchange Council, a group of companies and conservative lawmakers—popular in the Indiana state house—that has encouraged anti-climate initiatives.

Polling shows more than half of Hoosiers say climate change is indeed happening, though, and that includes some local officials. Jim Brainard, a Republican from the Indianapolis suburb of Carmel, is among the Indiana mayors who see economic opportunities in the shifting energy landscape and are taking action in their cities.

But a variety of Indiana residents think statewide efforts are crucial, and they’re pressing officials to do something. What’s driving them is the knowledge that the science isn’t mixed on whether the world is warming, whether humans are largely to blame and whether that’s bad for us. The major point of debate among scientists now is just how bad it will be.

Last fall Gabriel Filippelli coordinated a letter, signed by 23 Indiana academics, that urged Pence to draw on the educators’ in-state expertise on climate and its impacts. It recommended a plan for “mitigation and adaptation strategies … to protect energy and transportation infrastructure, the health of the public and economic development.”

“It actually wasn’t intended to be political, but rather, ‘You have a lot of resources right here in Indiana, in your back yard, people who are expert in this and can give you better advice than maybe you’re receiving,'” said Filippelli, a professor of earth sciences at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

He said he got “zero” response from the Pence administration, which also did not answer the Center for Public Integrity’s questions about the matter.

Anita Wylie is trying a different tack. She’s suing.

Wylie, an attorney who once worked for the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, is asking a trial court in Indianapolis to make the state develop a climate action plan. It’s something two-thirds of states now have, and it’s what the academics’ letter meant by mitigation and adaptation strategies.

A Pence spokeswoman did not respond to a question about the lawsuit, but the state argued in a motion to dismiss the case that it is not required to write a climate plan.

Wylie, now retired, says she is pursuing the lawsuit for her young grandsons and in memory of her father, a meteorologist deeply concerned about climate change.

“Indiana’s my state,” she said. “I’m embarrassstroed by the positions that the government’s taken.”

Hopkins reported this story with the support of the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism and the National Fellowship, programs of the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism.

Center for Public Integrity news developer Chris Zubak-Skees contributed to this story. Reposted with permission from our media associate The Center for Public Integrity.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe