Alabama Power's James H. Miller Jr. Electric Generating Plant. Eric Chaney / weather.com

By Elizabeth Hernandez and Eric Chaney

Up close, the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases in the U.S. isn’t as big as you’d expect it to be. From most angles, you can’t even see it until you’re right on top of it.

But hit the right gap in the rolling hills of north-central Alabama, and the James H. Miller Jr. Electric Generating Plant looms large even from miles away. Nestled on about 800 acres on the Locust Fork of the Black Warrior River, the plant is one of Alabama Power’s coal-burning workhorses, putting out enough electricity to power about a million homes. It virtually never stops running—and never stops producing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

As the view shifts, so does public opinion.

From certain angles, the plant is a pollution-belching monster harming both the environment and the health of communities. Change your perspective a bit, and Miller is a source of good-paying jobs, a means to raise a family in an area where economic opportunities are thin.

Paul Dollar, 75, who has lived just a few hundred yards from the plant property for more than 30 years, sees Miller both ways. On one hand, there’s dust and noise: “This thing I believe is getting my health and it’s bothering me.” On the other, Dollar and his daughter Tammy can name a dozen friends, relatives and neighbors who work for the plant, its contractors, or in one of the related service industries.

“To their credit, Alabama Power is a good corporate citizen. They provide good jobs. They do a lot in the community for charity and such,” said Scotty Colson, a lawyer in Birmingham, 16 miles southeast of the plant. But “you don’t get the impression that [pollution] is a high priority. They’re pretty much OK with shifting the cost onto people who have a problem with what their byproduct is.”

Alabama Power is a subsidiary of the Southern Company, which owns 11 utilities in nine states. Southern has spent nearly $12 billion on pollution controls at its plants since 1990 and “is committed to comply with all environmental laws and regulations,” spokesman Terrell McCollum wrote in a statement for this article.

But Colson, a clean-air advocate, said those costs have been passed on to customers—both directly on their utility bills and indirectly through impacts on health and climate.

“They start putting the onus on everybody else,” he said, “when in fact they have spent quite a lot with lobbying to fight regulations and delay regulations.” Southern spent more than all but a dozen other U.S. companies on federal lobbying during the 2016 election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics—nearly $14 million.

Colson has lived in the Birmingham area for all of his 58 years and fought asthma for most of them. Miller’s discharges of greenhouse gases and noxious substances have taken a toll, he said, not only on the environment but also on his lungs.

“You rationalize it by saying, ‘I’m taking care of my family first,'” he said. “You rationalize it by saying, ‘Oh, it really doesn’t do any harm.’ That’s your basic climate denial and science denial, which is epidemic in some areas here.”

But the science doesn’t lie. Researchers around the world have repeatedly offered proof that climate change is happening and that humans are causing it.

Colson, at least, has no doubts.

“You can question the science,” he said, “but you can’t question the reality of my lungs.”

“Old news”

In 2016, average global temperatures hit record highs for the third year in a row, according to NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Most of the warming since the late 19th century has happened since the early 1980s, the agencies said.

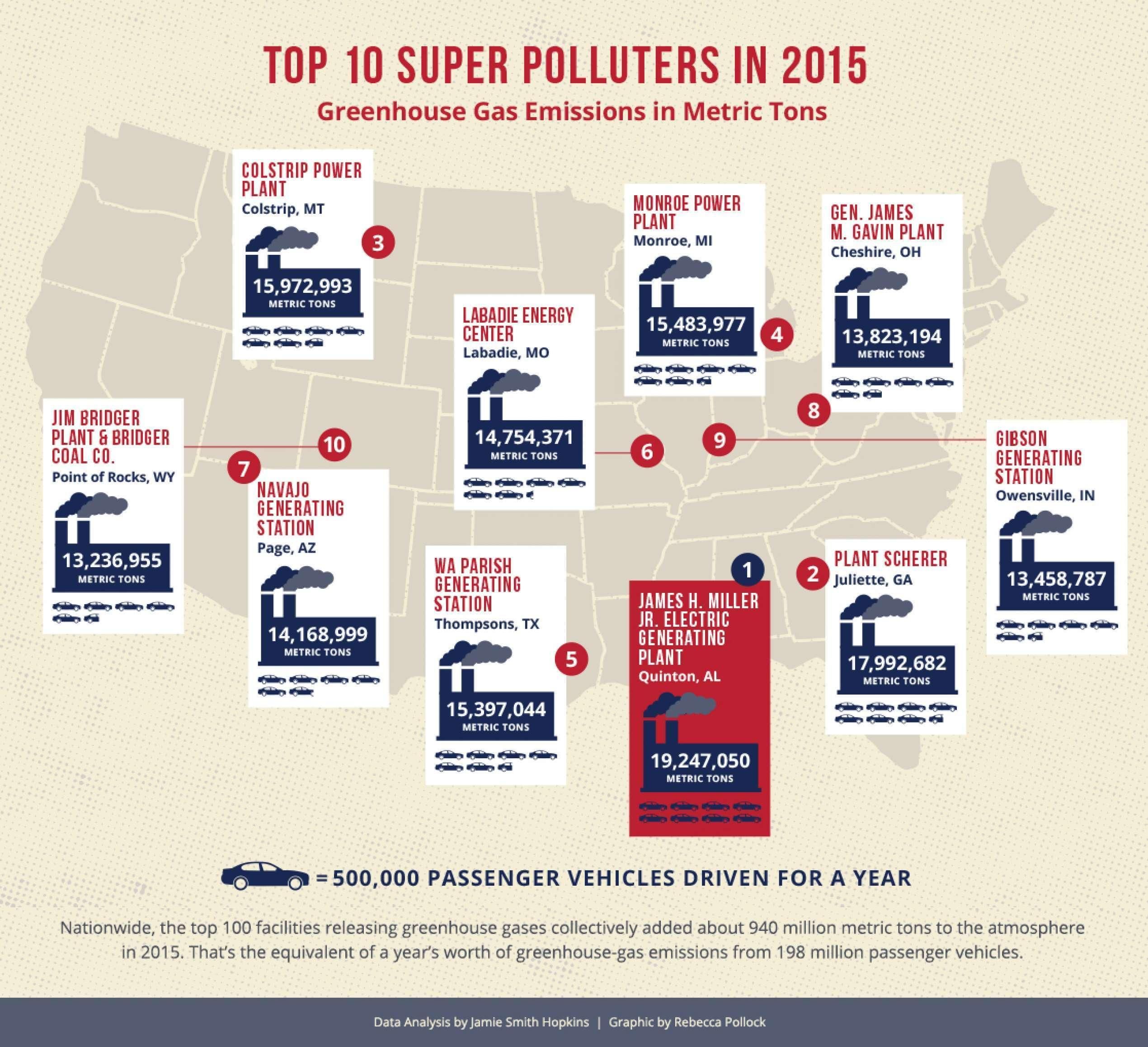

Miller was the nation’s biggest emitter of planet-warming gases in 2015, releasing more than 19 million metric tons—the equivalent of about four million passenger vehicles driven for a year. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data show that Miller has been one of the top three greenhouse gas-producing U.S. facilities—not just power plants—since federal tracking began in 2010.

But that doesn’t seem to bother its owner.

“That’s kind of old news,” Alabama Power spokesman Michael Sznajderman said. “It’s jostled for that No. 1, No. 2, No. 3 spot for years.”

Southern CEO Tom Fanning told CNBC there wasn’t proof that carbon dioxide is the key driver of climate change—contradicting the overwhelming scientific evidence.

Birmingham attorney Scotty Colson, who has asthma, said Alabama Power provides good jobs—but also air pollutants that affect the climate and, he said, his lungs.

“Is climate change happening? Certainly. It’s been happening for millennia. That’s not the issue, OK?” he said.

Though the Miller plant tops the greenhouse-gas list, many large facilities in the U.S.—particularly coal-fired power plants—are also outsize emitters. The 100 industrial sites giving off the most climate-altering gases together make up hardly more than one percent of the facilities reporting to the EPA, but account for nearly a third of those discharges. Toxic air emissions are also heavily concentrated, according to a 2016 Center for Public Integrity investigation in partnership with weather.com.

Miller, for its part, halved toxic releases from its stacks between 2010 and 2015, following many years of far higher levels, EPA data show. The steep plunge came after Alabama Power installed pollution controls to comply with federal regulations. These technologies, like scrubbers and ozone-combating machinery, reduce sulfur dioxide, fine particles and other contaminants associated with coal-burning, Sznajderman said.

Still, some of Miller’s remaining emissions can damage the lungs and, research suggests, increase the risk of heart attack and stroke. The nitrogen oxides coming from Miller, tracked separately by the EPA, are a key ingredient in ground-level ozone, or smog, that’s particularly hard on some people. This county, Jefferson, received an “F” grade from the American Lung Association for its ozone levels.

“That is probably my main trigger for asthma issues,” Colson said. “I kind of connected the dots … Days when the ozone is high are the days that I feel really bad.”

It used to be the steel mills, pumping out brownish “air you could chew,” that cost him days at school and basketball games with his friends. As the mills cleaned up or closed and the sky turned blue again, Colson still noticed a burning sensation when he would breathe.

Miller, he believes, is the primary culprit. The plant was fouling the air all those years, he said, “but you basically didn’t notice that because it was part of an even worse pollution problem.

Staggering costs

Southern is one of the biggest greenhouse-gas emitters in the country—its plants collectively pumped out more than 100 million metric tons in 2015, EPA data show.

Companywide, greenhouse-gas emissions in 2015 were about 25 percent lower than they were a decade earlier, according to Southern spokesman McCollum. “This reduction was achieved without federal mandates, while delivering to customers the benefits of a more diverse generating fleet,” he wrote.

The problem with climate change is that greenhouse gases sent into the atmosphere today lock in big costs later. A report from online real estate site Zillow said almost 1.9 million homes worth $882 billion combined “are at risk of being underwater by 2100.”

Add relocation costs for those affected and the loss of tourism dollars in coastal communities, and numbers soar into the trillions—for just a fraction of the damage that experts fear global warming will cause.

Alabama Power’s Sznajderman said Southern is “certainly cognizant of climate change and those carbon issues, and we’re doing some of the leading research in that area.” Indeed, it operates the National Carbon Capture Center—a complex near Wilsonville, Alabama, aimed at finding ways to sequester carbon dioxide from coal-fired power plants—for the U.S. Department of Energy.

But none of the technologies is ready for deployment at Miller, Sznajderman said. Southern’s Kemper plant in Mississippi, an effort to gasify coal and capture about two-thirds of the carbon, is more than $4 billion over budget.

Southern also is over budget on a project in Georgia, an expansion of the Alvin W. Vogtle nuclear plant that the company is promoting as a solution for moving away from carbon-based “dirty” energy sources like coal.

Two new power generating units were originally scheduled to be completed by 2016 and 2017, at a cost of $14 billion, but more recent estimates put the project about three years behind with a final price tag of $21 billion.

Construction is only about 43 percent complete, and David McKinney, Georgia Power’s vice president of nuclear development, has said the company is assessing the costs of abandoning the project altogether. Georgians are angry about having to foot the bill.

Fighting the Clean Power Plan

For now, the federal government doesn’t pose a threat to Miller’s place atop the greenhouse-gas list. In March, President Donald Trump ordered the EPA to scrap its Clean Power Plan, an Obama administration carbon-cutting initiative. On June 1, Trump announced America’s withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement.

Trump’s promises to decrease regulations and support the coal industry play well here. He didn’t win Jefferson County, home of Birmingham, but in three of the counties near the plant, more than 80 percent of voters chose him.

In February 2016, while Barack Obama was president, representatives of Southern decried the Clean Power Plan as an example of the “EPA’s overreaching mandates.” The U.S. Supreme Court’s stay on the rule that month was “the right decision for customers” and went a long way toward “preserving states’ authority,” Southern said. Alabama Power took an active role in the fight, joining those suing to stop the plan.

Alabama’s then-attorney general, Luther Strange, called the stay a tremendous victory over “an unprecedented and illegal EPA rule. … The Obama administration’s EPA rule would shutter coal-fired power plants around the country, including in Alabama, while killing jobs and raising power bills for hard-working families.”

The state did not join the EPA in its years-long legal battle, largely during the George W. Bush administration, to get Alabama Power to add environmental controls to power plants. The federal agency and the company settled claims related to the Miller plant in 2006.”

‘Biggest employer around’

Miller represents a steady source of jobs in the rural swath of northwestern Jefferson County.

“Alabama Power is the biggest employer around,” Tammy Dollar said. “Everybody needs a job, and there’s so many down there.”

Day in and day out, the parking lot is packed with cars, and the Dollars can rattle off a host of relatives who earn a living there: an in-law who drove a coal train, a distant cousin who works as a security guard, a first cousin who’s “way up there now.”

According to Alabama Power, salaries at the plant range from around $36,000 to about $120,000 a year, or about $74,000 on average. The company’s Sznajderman said Miller employs around 365 people but can have as many as 1,500 contractors on site during planned maintenance outages. The plant pays about $12 million a year in property taxes.

It’s not an easy place to live beside—Paul Dollar isn’t the only neighbor to say that. “I’ve called them. I’ve tried to ask them to buy me out,” he said. “They say, ‘Oh, we’ll let you know. We’re gonna let you know.’ And I said, ‘Are you waiting on me to die?'”

Sznajderman said Alabama Power has no record of an inquiry from Dollar but “we plan to follow up with him.”

His complaints aside, Dollar said the plant’s benefits are important—worth the coal dust on his car and racket that sometimes makes it impossible to sleep.

“Even if I could, I wouldn’t shut it down because that’s jobs for people,” he said. “I’m not trying to put people out of business. I don’t want to stop progress or people living, you know. If I had anything to do with that, if I had the power to shut it down: No, huh uh, I’d build more. I would let the plant go on giving people jobs and let it keep moving.”

Nationally, however, the outlook isn’t good. Pressured by low natural gas prices, coal lost its spot as the top fuel for electricity generation in 2016, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Coal’s share fell from about 42 percent in 2011 to 30 percent last year, the EIA reported.

Virtue and vice

There’s a stubbornness ingrained in the Scots-Irish ancestry of many of the people in this area, Colson said. This translates into fierce loyalty to the community and the Miller plant.

“That loyalty is a virtue,” Colson said, “but that loyalty, in the face of reality, becomes a vice.”

The plant is a mainstay, its benefits obvious. Climate change can seem nebulous and far off, even though some of its effects are already manifesting.

Nearly 70 percent of the people in Jefferson County believe in climate change, a 2016 Yale University study found, but only half believe it’s caused mostly by human activities.

Around 65 percent think global warming will “harm future generations” at least a moderate amount, but only 39 percent believe it will “harm me personally” to that extent.

There are many barriers to overcome. People here first must believe that climate change is real. Then they must believe that it’s harmful, that Miller is contributing to it and that they can do something about it.

That is, as Colson put it, one “tough row to hoe.”

In the case of Paul and Tammy Dollar, it’s not that they’re unconcerned about the plant’s contribution to climate change—it’s that the consequences seem too far down the road.

Ask them about global warming and they’ll launch into a story about coal dust on their cars or a neighbor who’s ill. That’s real. It’s there, to be touched and smelled and inhaled.

Denying science

The unhealthy gases, chemicals and metals Miller pumps into the air are on the decline. But its greenhouse-gas emissions haven’t fallen nearly as much. It puts out about one million more metric tons of greenhouse gases than the No. 2 facility in the nation, the Scherer power plant in Georgia, owned partly by Southern.

What lies ahead for power production in the South remains a question, particularly in Miller’s corner of Alabama. Michael Hansen, executive director of Gasp, a Birmingham-based environmental group, fears his state isn’t poised to move in a climate-friendly direction.

“It’s a struggle to figure out how to talk about these issues when so many—not just voters but also politicians and leaders—deny science,” he said. “People don’t even realize the force of greenhouse gases around them. We’re going to need all the help we can get here.”

But Colson has hope.

“There has been change—it does get better,” he said. “So when people say, ‘Oh, you’re just stubborn,’ or ‘You’re crazy to keep trying to see positive change in Alabama,’ I say, ‘Well, I might be crazy, but I’ve seen it.’ It does not come at a precipitous speed, but it does come with due diligence.”

Eric Chaney is a reporter with weather.com. Jamie Smith Hopkins of the Center for Public Integrity contributed to this story.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe