Air Pollution Kills Thousands of Americans Yearly – Here’s a Low-Cost Strategy to Help

A family living next to a Shell petroleum refinery plant pets their dogs on Nov. 9, 2019 in Norco, Louisiana. Andrew Lichtenstein / Corbis via Getty Images

By Jason West and Yang Ou

About one of every 25 deaths in the U.S. occurs prematurely because of exposure to air pollution. Dirty air kills roughly 110,000 Americans yearly, which is more than all transportation accidents and shootings combined.

When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) weighs decisions about air pollution regulations, it typically selects candidate actions from one or more sectors, such as electric power generation and industry. For each strategy considered, the agency carefully estimates the costs and benefits, then decides which actions to pursue.

We study air pollution and options for reducing it. In a newly published study, we flipped the traditional approach around by starting with the goal of finding emission control actions, among all sources, that could save a specified number of lives for the lowest cost. In doing so, we identified a set of low-cost actions to reduce air pollutant emissions from highly polluting industrial and residential sources, such as residential wood-burning furnaces, that can provide highly cost-effective health benefits.

The U.S. has made tremendous progress in reducing air pollution since 1990, and this has produced significant public health improvements. But air pollution still imposes a serious health burden on the U.S. population, and there are signs that past progress in improving air quality may now be leveling off. New ways of analyzing actions to control air pollution and its health impacts can help.

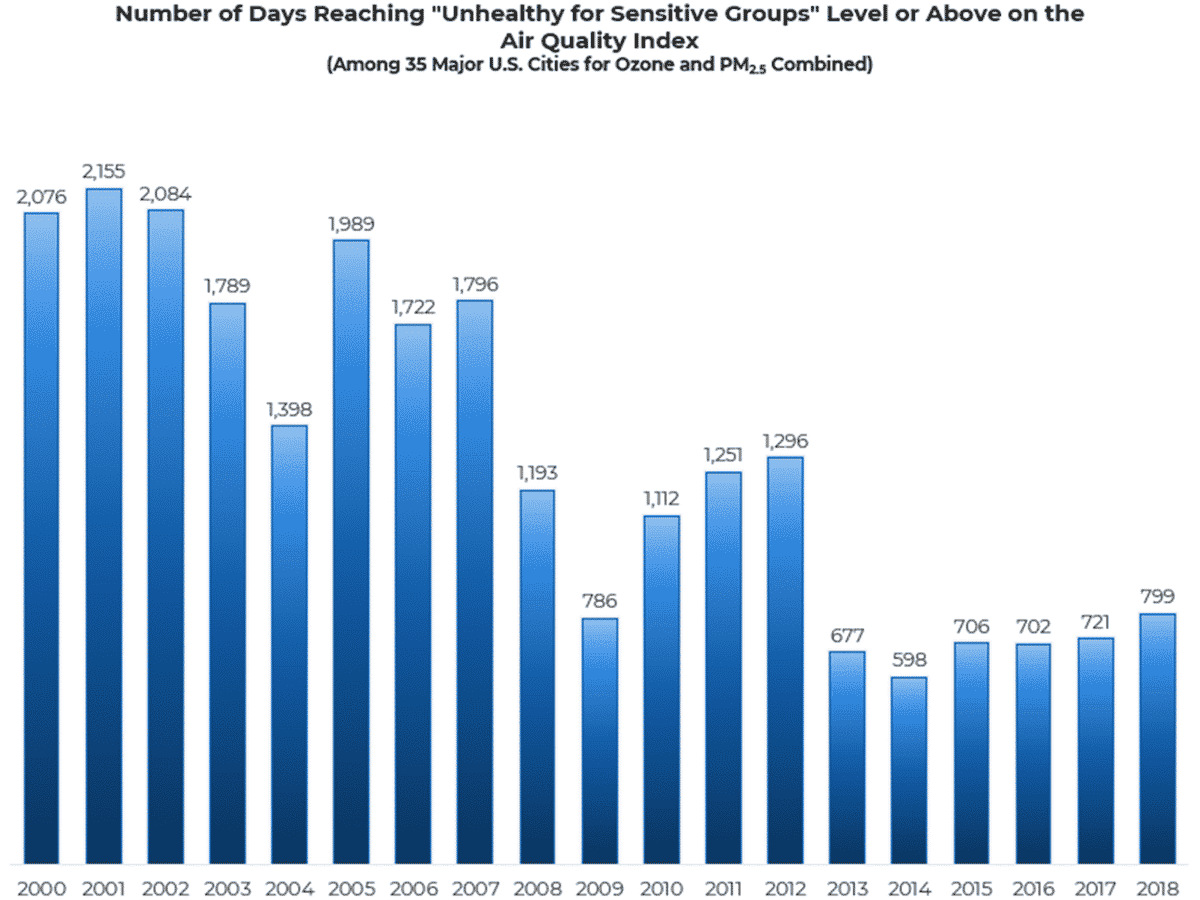

The number of bad air days in 35 major U.S. cities has plateaued since 2013. U.S. EPA

An Alternative Approach

Under the 1970 Clean Air Act, it is the EPA’s job to set National Ambient Air Quality Standards. These regulations limit concentrations of six major air pollutants that harm public health and the environment. Then each state adopts actions that will meet these standards, such as reducing emissions from power plants or large industries.

The EPA also sets limits on emissions from some specific sources over which it has legal authority, including new power plants and motor vehicles. In doing so, the agency aims for air that is considered healthy for all Americans to breathe.

For each strategy considered, the EPA often runs a full cost-benefit analysis. This approach requires a complex atmospheric model to estimate how each proposed action will affect air pollutant concentrations, and the health impacts that will result. This limits the number of options that can be considered.

Our study focused on fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5. We created a framework that simplified the complexity of the atmosphere and air pollution’s health impacts. For each U.S. state we calculated impact factors, which represent deaths related to PM2.5 exposure per ton of emissions of different chemical components from different sources. Then we fed these impact factors into an economic model of the U.S. energy system, allowing the model to calculate deaths for any strategy.

Next we set a limit on total deaths caused by PM2.5, and let the model select the least expensive set of actions that would meet energy needs – an important factor because energy use is a major air pollution source – while keeping PM2.5-related deaths below our ceiling. Our model projected future scenarios to 2050, so we considered different ceilings at various points in time, and observed the actions the model selected.

This alternative approach has the advantage of considering a wide range of possible control strategies that affect many different sources. It prioritizes the actions that most cost-effectively reduce premature deaths. Further, by considering these actions in the context of the broader energy system, we can include actions like fuel switching and energy efficiency as alternatives, and quantify consequences of actions throughout the U.S. energy system.

High Particulate Emitters

Using this approach, we pinpointed a set of sources whose emissions contribute disproportionately to PM2.5 mortality impacts. They include factories and other industrial facilities powered by coal and oil, and wood-fired residential furnaces. Emissions from these sources are rising and may continue to increase in the future without additional controls.

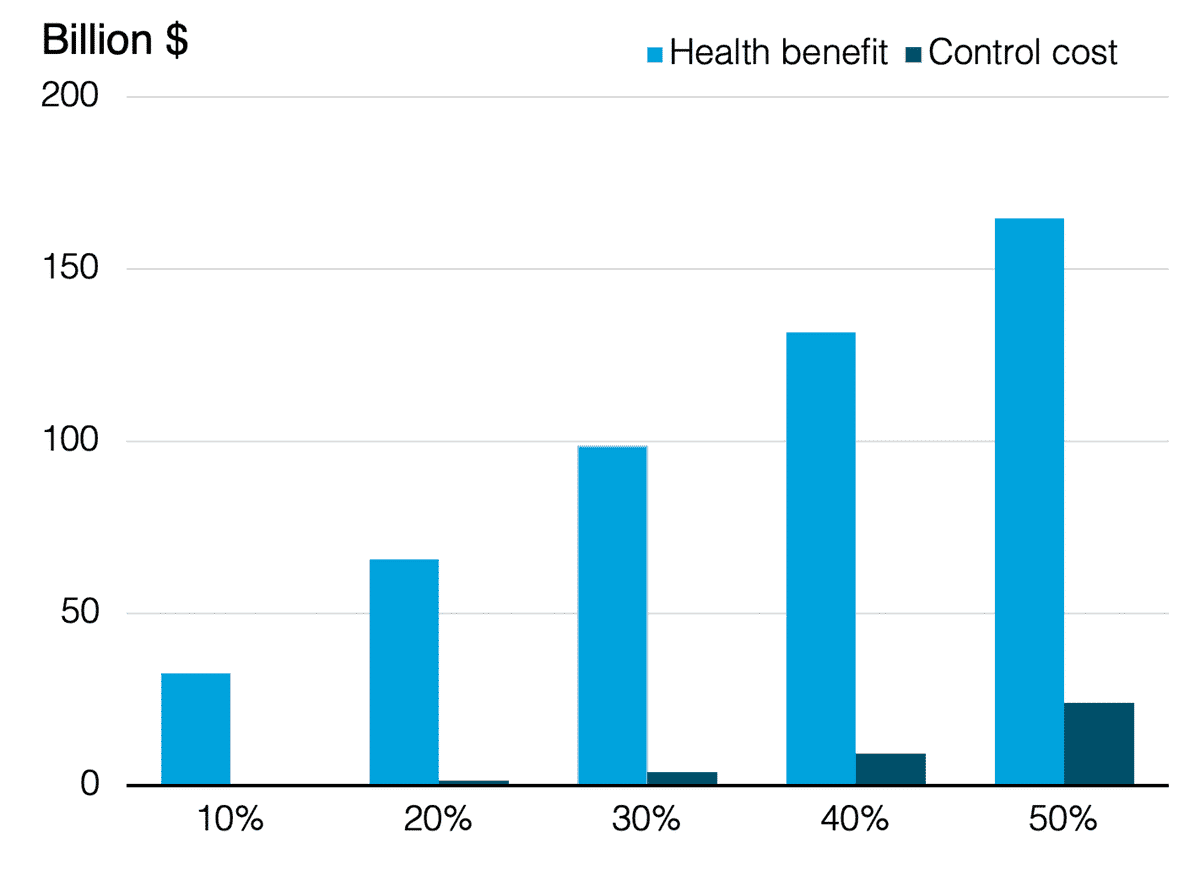

Our model showed that reducing emissions from these sources – mainly by electrifying them – could cut projected national air pollution-related deaths in 2050 in half very cost-effectively. Overall national health benefits from these reductions would be roughly seven times the cost of the pollution controls. As many studies have found, air pollution controls tend to be very cost-effective because these emissions cause people to die prematurely through cardiovascular diseases, stroke, lung cancer and other long-term illnesses.

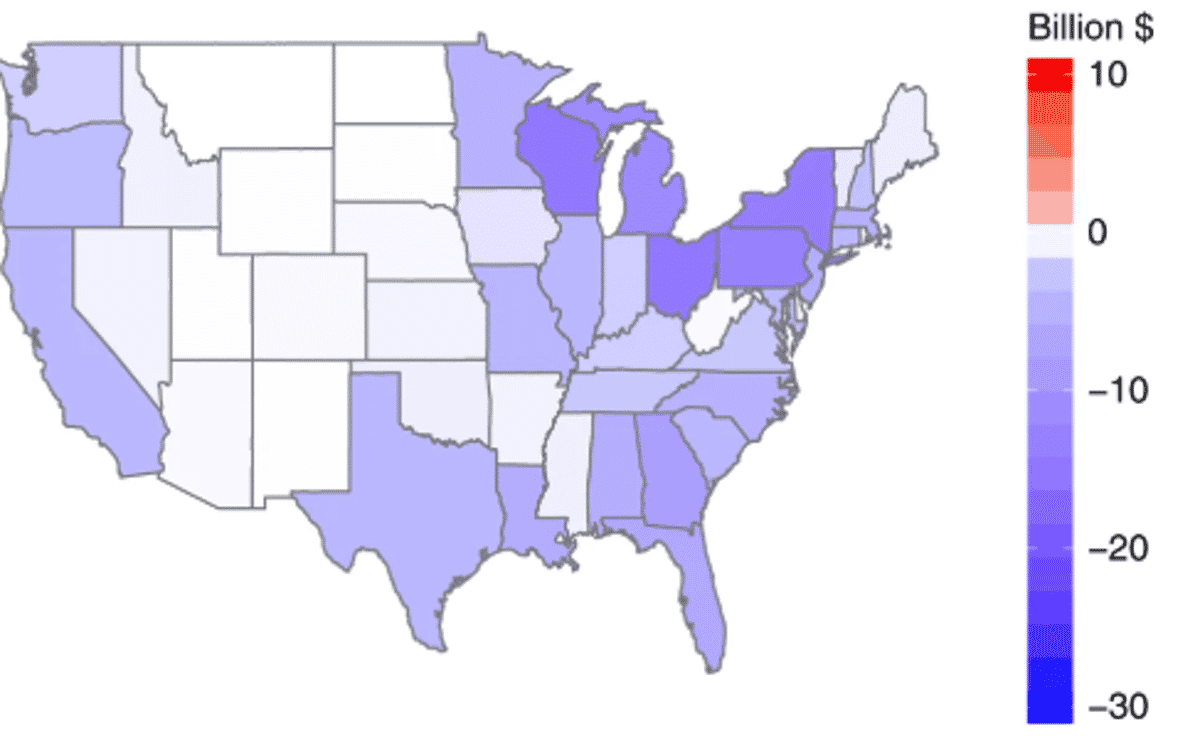

Reductions in the costs of PM2.5-related deaths due to emission reductions from each state, from a scenario that cuts projected national PM2.5-related deaths in 2050 in half. Ou et al., 2020., CC BY

Our study shows that this approach would reduce PM2.5-related emissions in each state. Progress would be greatest in northern and eastern states, including Ohio and Pennsylvania. These regions have many large industrial sources and are densely populated, which means that many people benefit from cleaner air.

Ohio has the largest potential for cost-effectively reducing PM2.5 deaths through cutting industrial coal emissions. California would benefit most from controls on residential wood burning, and Texas would see the greatest reductions in emissions from large petrochemical industries.

We also found that these actions had little influence on overall energy usage in the U.S., and therefore little effect on greenhouse gas emissions. This was interesting because previous research has found that most initiatives to reduce greenhouse gases – which typically involve switching to less-polluting fuels, such as going from coal to natural gas to renewables – also reduce air pollutant emissions, with significant benefits for public health. But the opposite is not true: Low-cost air pollution controls do not appear to have a big influence on U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

The costs and health benefits of identified low-cost actions to reduce projected national 2050 PM2.5-related deaths by 10% to 50%. Yang Ou, CC BY-ND

Looking Forward to Cleaner Air

Our approach finds the least-cost way of reducing the health impacts of fine particle pollution among all Americans. But it does not ensure that current standards will be met everywhere. One limitation of our method is that we analyzed emissions at the state level, but our current model does not permit us to look more closely at air quality and health impacts for individual urban areas within states that exceed fine particle standards.

Still, our methods offer another tool that the EPA and states can use to help in planning air quality improvements, and the actions identified as being cost-effective for improving health can be compared with those currently being pursued. Spotlighting alternative pollution reduction options can help federal and state regulators make decisions about energy resources and their environmental and health impacts for the coming decades.

As natural gas and renewable energy prices fall, energy industries are in the midst of a transition driven by new technologies and changing economics. As this shift takes place, it is important to consider how to meet new energy demands while reducing greenhouse emissions and the health impacts of air pollutants. We hope our methods will be useful in informing these decisions in the U.S. and elsewhere.

Inefficient wood stoves and wood-burning furnaces are major fine particle sources. Madison & Dane County Public Health

Jason West is a professor of environmental sciences and engineering at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Yang Ou is a postdoctoral associate at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Disclosure statements: Jason West receives funding from the EPA, NASA, NSF, the Donald and Jennifer Holzworth Faculty Acceleration Fund in Climate Change, and the State of North Carolina.

Yang Ou was supported by the Research Participation Program at the Center for Environmental Measurement and Modeling, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE).

Reposted with permission from The Conversation.

- Trump Administration Removes Federal Database That Tracked ...

- Half of U.S. Air Pollution Deaths Linked to Out-of-State Emissions ...

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe