Every year, we hear about the latest oil spills, pipeline explosions and pollution…but we rarely see how people and environment are impacted over time. Public Herald is embarking on a new series “American Albatross” to investigate the environmental legacy of fossil fuel in America and solutions for cleaning it up. We begin in Aliceville, Alabama.

Efforts to clean up an Alabama oil spill are under scrutiny after a train carrying 2.7 million gallons of North Dakota Bakken crude oil exploded last month, spilling into wetlands just outside the town of Aliceville. Photojournalist John Wathen captured video of cleanup efforts one week after the Nov. 7 derailment, and the footage prompts questions about the efficacy of methods being used.

[vimeo_embed //player.vimeo.com/video/80790113?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0 expand=1]

Wathen wasn’t the only citizen responder in Aliceville, AL. He was joined by Scott Smith, who’s visited major oil spills across the globe to deploy his biodegradable technology, OPFLEX, that can absorb oil and other toxins from polluted water. Wathen and Smith tried to reach the wetland to assess the damage and help stop the oil from moving downstream. But they were turned away by railroad personnel and threatened with the FBI. Genesee & Wyoming railroad spokesperson Michael Williams wouldn’t confirm or deny the FBI’s involvement and redirected Public Herald to the Bureau.

The footage captured by Wathen shows clean up workers spraying what appears to be water into the oil spill.

After seeing Wathen’s footage, Smith wrote to the railroad company, Genesee & Wyoming, to express his concerns about the methods being used to clean up the spill:

It appears from the photos sent to me that water is being used to spray down the oil in the wetlands surrounding Aliceville, AL. There are much better options to remove the oil and help prevent further damage to the wetlands. If it rains anytime soon, there is little doubt that the oil in the water will spread downstream and things can be done now to prevent this.

Smith believes his own technology may be a better way. After the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, Smith sold BP more than 2 million square feet of OPFLEX for cleanup. OPFLEX is an open-celled, sponge-like material modeled after the human lung and sometimes takes the shape of eelgrass to absorb oil and other toxins from polluted water, both on and below the surface.

According to Williams, the spray method revealed in Wathen’s footage is “a process used to corral the oil within the containment booms prior to skimming.” However, workers appear to be spraying away from booms in some instances and towards unprotected shorelines. Smith believes the workers are actually using an outdated, defunct “dilution is the solution to pollution” method.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Region IV, who responded to the spill, was not available for initial comment about the spraying.

According to Smith, when water is sprayed onto a shale oil spill, some toxins mixed with the oil dissolve below the surface of the water. Some of these toxins are naturally-occurring and some are byproducts of the drilling process used to extract Bakken crude, called fracking, which involves hundreds of chemicals that return to the surface with recovered oil.

How Are Oil Spills Cleaned Up?

In nearly all oil spills, containment booms are used as floating buffers to try and corral oil resting on the surface of water for skimming. Preventing oil from reaching shore is a major concern, given that oil is virtually impossible to remove from soil. The EPA and industry alike also use absorbent padding at waters edge in order to try and keep the oil off the shore.

When asked about the railroad’s cleanup efforts, Williams wrote to Public Herald that “air and water monitoring began on the morning of the derailment, and the site will be remediated.”

The railroad has a top oil-cleanup contractor on site who is experienced with crude oil responses for pipelines, exploration companies, railroads and shipping companies and has an established working relationship with EPA Region IV and the State of Alabama. The railroad is working closely with the EPA who are on site daily.

Williams later added their “top oil-cleanup contractor” is U.S. Environmental Services (USES), the same company involved in cleanup efforts of the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico and others.

Of course, part of remediation involves knowing precisely how and what’s been spilled. Though the cleanup and investigation of how the train derailed and exploded in Alabama is ongoing, Williams informed Public Herald that the railway was up and running ten days after the incident and trains carrying Bakken crude are being diverted around Aliceville.

Series of Spills Reveals Crude Trend

Four months before the Alabama spill, Smith visited another oil train disaster in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, where railcars—also carrying Bakken crude oil—derailed and exploded killing more than 40 people and decimating half the town.

CBC News Montreal reported in August that the “U.S. Department of Transportation…authorities were worried prior to the Lac-Mégantic disaster about the transport of oil from North Dakota on trains.” Another CBC News report states that Lac-Megantic investigators found it “unusual for crude oil to burn so fiercely.”

Smith has sampled and tested Bakken crude. According to him, not only is Bakken crude lighter and more volatile than other oils, but no one is testing or “fingerprinting” each shipment before placing it in railcars or pipelines for transport. “The objective is to pump it and load it,” Smith told CBC News Montreal.

Smith offered his test results to help with Genesee & Wyoming’s ongoing investigation. “I have done baseline fingerprinting of Bakken crude oil in its ‘pure form’…This data might help Genesee & Wyoming assess exactly what was in the tankers that exploded.”

CBC News also reported tests of Bakken crude by one oil company which showed ten times the amount of benzene in Bakken oil as compared with others, as well as hydrogen sulfide, leading some experts to wonder about the crude’s propensity to easily ignite.

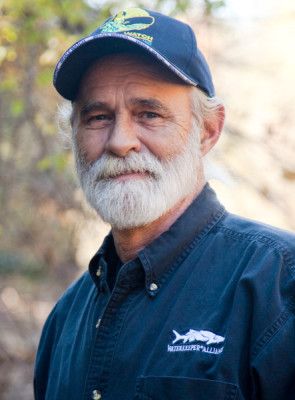

Like Smith, John Wathen has responded to many environmental disasters. As Hurricane Creekkeeper of the international Waterkeeper Alliance, Wathen responded to the 2008 Kingston coal ash disaster in Tennessee and the BP Gulf of Mexico spill in 2010, which won him the honor of being named 2012 River Hero. His documentation of these incidents gives a close-up look at how spills are handled.

Aliceville is just the latest in a series of spill disasters in North America, topping a growing list of incidents related to fossil fuel’s production, transport, distribution, and waste disposal. Setting aside natural gas facility explosions and coal ash spills, here’s a list of some of the oil spill disasters in the U.S., or involving U.S. companies, in just the last three years:

Jan. 11, 2010 – Aleutian Islands, AK – Adak Petroleum tank spill

Jan. 23, 2010 – Port Arthur, TX – ExxonMobil tanker ship hit by barge, spill

April 7, 2010 – Delta National Wildlife Refuge, LA – ExxonMobil pipeline contractor spill

April 20, 2010 – Gulf of Mexico, U.S. – BP Deepwater Horizon explosion, spill

May 1, 2010 – Niger Delta, Nigeria – ExxonMobil spill

May 25, 2010 – Anchorage, AK – BP Trans-Alaska pipeline spill

June 11, 2010 – Salt Lake City, UT – Chevron Red Butte Creek oil spill

July 26, 2010 – Kalamazoo, MI – Enbridge pipeline rupture into Kalamazoo River

July 27, 2010 – Barataria Bay, LA –Boat struck a Cedyco Corp. abandoned wellhead, five day spill

Dec. 1, 2010 – Salt Lake City, UT – Chevron Red Butte Creek oil spill, part II

March 18, 2011 – Gulf coast, LA – Oil spill, unknown origin

July 1, 2011 – Billings, MT – ExxonMobil Yellowstone River oil spill

July 13, 2011 – Prudhoe Bay, AK – BP pipeline leak, spill

Nov. 8, 2011 – Campos Basin, Brazil – Chevron offshore rig oil spill

Dec. 21, 2011 – Niger Delta, Nigeria – Shell offshore oil spill

April 28, 2012 – Torbert, LA – Exxon Mobile pipeline spill

Oct. 29, 2012 – Sewaren, NJ – Arthur Kill oil spill after Hurricane Sandy

Dec. 21, 2012 – McKenzie County, ND – Newfield well blowout, spill

March 9, 2013 – Magnolia, AR – Lion Oil refinery leak

March 26, 2013 – Willard Bay, UT – Chevron pipeline rupture, spill, groundwater contamination

March 30, 2013 – Mayflower, AR – ExxonMobil Pegasus pipeline rupture, spill

May 7, 2013 – Milner, ND – TransCanada pipeline leak, spill

May 9, 2013 – Indianapolis, IN – Marathon Oil pipeline leak, spill

May 18, 2013 – Cushing, OK – Enbridge storage terminal leak, spill

Sept. 25, 2013 – Tioga, ND – Tesaro Logistics pipeline rupture, spill

Nov. 7, 2013 – Aliceville, AL – Genesee & Wyoming crude train explosion, spill

This is not a comprehensive list. According to an analysis by EnergyWire, more than 17,000 spills were reported between 2010-2012 in the U.S.

“Best” Method of Transporting Oil

Due to a surge in American fossil fuel production in recent years, oil-by-rail has become an alternative for many companies at a time when pipelines are taboo, crowned in controversy by the Keystone XL. The L.A. Times reported in September that railroads are carrying 25 times more crude oil than they were five years ago.

Genesee & Wyoming’s Michael Williams wrote to Public Herald, “Rail is the safest means of ground-freight transportation…As a common carrier, the railroad has a legal obligation to transport these materials.”

Both railways and pipelines can be “common carriers” which are legally required to carry all freight, if space allows and fees are paid, and may not refuse unless reasonable grounds exist. Under international law, a common carrier is liable for damage to freight as well, with four exceptions: “An act of nature, an act of the public enemies, fault or fraud by the shipper, [or] an inherent defect in the goods.”

Whether pipelines or railways are “safer” for transport of hazardous materials like crude oil is debatable, but writer Russ Blinch gives an interesting analogy:

Looking at pipelines versus rail tankers is really like asking, “Should I drive the car with bad brakes or the one with bad tires?

For those living along routes for transporting hazardous materials, whether by pipe or by rail, it’s unlikely anyone’s taken time to ask which methods or cleanup technology communities prefer industry use.

Visit EcoWatch’s FRACKING page for more related news on this topic.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe