Ocean plastic pollution is an increasingly devastating crisis, and this new infographic shows exactly where the plastic trash is coming from, where it ends up and why it’s important to start our fight against this environmental scourge at the beach.

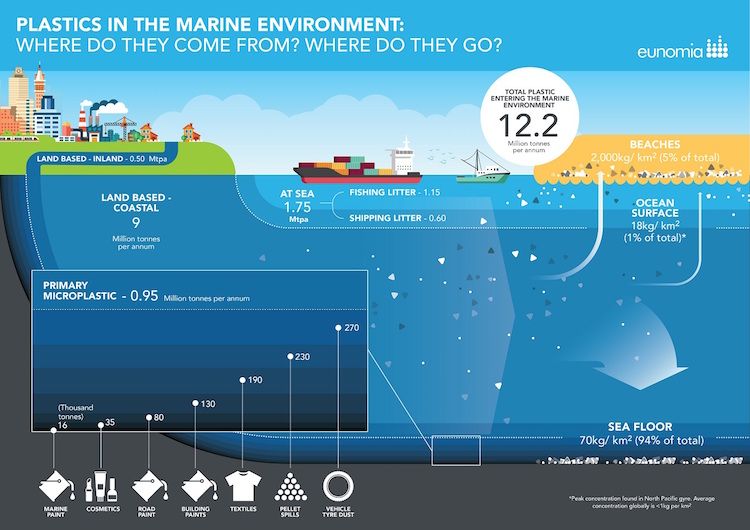

The graph, provided by UK-based Eunomia Research & Consulting, shows that more than 80 percent of the annual input of plastic litter, such as drink bottles and plastic packaging, comes from land-based sources. The remainder comes from plastics released at sea, such as lost and discarded fishing gear.

Significantly, Eunomia was able to come up with a new estimate of annual global emissions of “primary” microplastics, such as microbeads, fibers or pellets. (“Secondary” microplastics are the result of larger pieces of plastic breaking down into smaller pieces.)

The firm calculated that emissions of microplastics range from 0.5 to 1.4 million tonnes per year, with a mid-point estimate of 0.95 million tonnes. Vehicle tires are the biggest culprits, releasing 270 thousand tonnes of debris into our waterways annually.

These tiny non-biodegradable pieces of plastic are a cause for worry, as they are being gobbled up by plankton and baby fish like junk food, and works its way up the food chain. Microplastics have been found in in ice cores, across the seafloor, vertically throughout the ocean and on every beach worldwide. As EcoWatch mentioned previously, microplastics are also very absorbent, meaning they pick up the chemicals it floats in.

The firm compiled a report of their research that was released earlier this month. The report shows an astounding 94 percent of the plastic that enters the ocean ends up on the ocean floor, with an estimated 70 kilograms of plastic per square kilometer of sea bed on average.

The report thus highlights a common misunderstanding in which ocean plastic is often portrayed as a Texas-sized garbage patch floating in the middle of the ocean. According to a press release of the study:

Despite the high profile of projects intended to clean up plastics floating in mid-ocean, relatively little actually ends up there. Barely 1% of marine plastics are found floating at or near the ocean surface, with an average global concentration of less than 1kg/km2. This concentration increases at certain mid-ocean locations, with the highest concentration recorded in the North Pacific Gyre at 18kg/km2.

By contrast, the amount estimated to be on beaches globally is five times greater, and importantly, the concentration is much higher, at 2,000kg/km2. While some may have been dropped directly, and other plastics may have been washed up, what is clear is that there is a “flux” of litter between beaches and the sea. By removing beach litter, we are therefore cleaning the oceans.

Although it wasn’t explicitly stated, the highly publicized “Ocean Cleanup Project” (OCP) comes to mind. The scheme, which is being brought to life by its young Dutch inventor Boyan Slat, aims to clean half the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in a decade via a static platform that passively corrals ocean plastics with a V-shaped boom.

While Slat and 70 other scientists and engineers have composed a 530-page feasibility report on the project, critics have written off the idea. As Dr. Marcus Eriksen, 5 Gyres co-founder and an ocean scientist whose research was cited in the Eunomia study wrote, “There are no islands of plastic, rather a smog of plastic that pervades the oceans.”

Eriksen suggested that Slat move the array upstream to capture trash before it fragments.

“Many countries around the world are deploying structures of all kinds to catch trash downstream, from nets to waterwheels, with the last stop at river mouths,” Eriksen wrote. “OCP could contribute their engineering expertise to the growing industry designing systems to tackle waste upstream.”

As for how you can help, Dr. Chris Sherrington, principal consultant at Eunomia, explained why beach cleanups are one of the best ways to fight ocean plastic.

Chris Sherrington explains that beach clean ups are an effective & valuable way to stop plastics entering the sea pic.twitter.com/mOAZiOZICc

— Eunomia Research & Consulting (@Eunomia_RandC) May 24, 2016

“When plastic does get into the sea, it’s clear that efforts to remove it from the beaches are extremely valuable,” he said. “They’re generally more accessible than the mid-ocean, there’s more material there overall than there is floating, and it is much more concentrated on beaches.”

Sherrington added that policies on cutting plastic use, such as taxes on everyday plastic items and recycling incentives, could stop the waste at the source.

“Prevention is usually better than cure, and there’s a lot more we could do to stop plastic from entering the marine environment in the first place,” he said. “Preventing waste and preventing litter can go hand in hand. The charge on single-use carrier bags is a cost-effective step in the right direction, but we should be considering the same approach for other commonly littered plastic items, like take-away cups and disposable cutlery. Deposit refunds on beverage containers would help incentivize people to return them for recycling, and reduce the amount littered.”

Here are some other key points from the Eunomia report:

- Barely 1 percent of marine plastics are found floating at or near the ocean surface, with an average global concentration of less than 1kg/km2.

- This concentration increases at certain mid-ocean locations, with the highest concentration recorded in the North Pacific Gyre at 18kg/km2. By contrast, the amount estimated to be on beaches globally is five times greater, and importantly, the concentration is much higher, at 2,000kg/km2.

- While some may have been dropped directly, and other plastics may have been washed up, there is a “flux” of litter between beaches and the sea. By removing beach litter, we are therefore cleaning the oceans.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Found in Rio de Janeiro Waterways Ahead of Olympics

Chile’s Salmon Industry Using Record Levels of Antibiotics to Combat Bacterial Outbreak

There’s Nothing Average About This Year’s Gulf of Mexico ‘Dead Zone’

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe