Iron is a mineral that serves several important functions in the body. Its main function is carrying oxygen throughout your body and making red blood cells (1).

Iron is an essential nutrient, meaning you must get it from food. The recommended daily intake (RDI) is 18 mg. Interestingly, the amount your body absorbs is partly based on how much you have stored.

A deficiency can occur if your intake is too low to replace the amount you lose every day (2).

Iron deficiency can cause anemia and lead to symptoms like fatigue. Menstruating women who don’t consume iron-rich foods are at particularly high risk of deficiency.

Here are 11 healthy foods that are high in iron.

1. Shellfish

Shellfish is tasty and nutritious. All shellfish is high in iron, but clams, oysters and mussels are particularly good sources.

For instance, a 3.5-ounce (100-gram) serving of clams contains 28 mg of iron, which is 155 percent of the RDI (3).

What’s more, a lot of the iron in shellfish is heme iron, which your body absorbs more easily than the non-heme iron found in plants (4).

A serving of clams also provides 26 grams of protein, 37 percent of the RDI for vitamin C and a whopping 1,648 percent of the RDI for vitamin B12.

In fact, all shellfish is high in nutrients. Shellfish has also been shown to increase the level of heart-healthy HDL cholesterol in your blood (5).

Although there are legitimate concerns about mercury and toxins in certain types of fish and shellfish, the benefits of consuming seafood far outweigh the risks (6).

Bottom Line: A 100-gram serving of clams provides 155 percent of the RDI for iron. Shellfish is also rich many other nutrients.

2. Spinach

Spinach provides many health benefits for very few calories.

3.5 ounces (100 grams) of cooked spinach contain 3.6 mg of iron or 20 percent of the RDI (7).

Although this is non-heme iron, which isn’t absorbed very well, spinach is also rich in vitamin C.

This is important, since vitamin C significantly boosts iron absorption (8).

Spinach is also rich in antioxidants called carotenoids that may reduce the risk of cancer, decrease inflammation and protect your eyes from disease (9, 10, 11, 12).

Consuming spinach and other leafy greens with fat helps your body absorb the carotenoids, so make sure to eat a healthy fat like olive oil with your spinach (13).

Bottom Line: Spinach provides 20 percent of the RDI for iron per serving, along with several vitamins and minerals. It also contains important antioxidants.

3. Liver and Other Organ Meats

Organ meats are extremely nutritious. Popular types include liver, kidneys, brain and heart. All of these are high in iron.

For example, a 3.5-ounce (100-gram) serving of beef liver contains 6.5 mg of iron or 36 percent of the RDI (14).

Organ meats are high in protein and rich in B-vitamins, copper and selenium. Liver is especially high in vitamin A, providing an impressive 634 percent of the RDI per serving.

Organ meats are also among the best sources of choline, an important nutrient for brain and liver health that many people don’t get enough of (15).

Bottom Line: Organ meats are good sources of iron and liver contains 36 percent of the RDI per serving. Organ meats are also rich in many other nutrients.

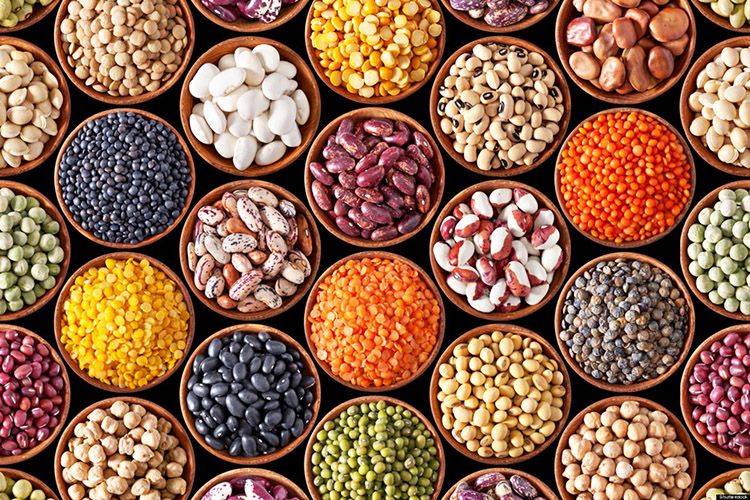

4. Legumes

Legumes are loaded with nutrients.

Some of the most common types of legumes are beans, lentils, chickpeas, peas and soybeans.

They’re a great source of iron, especially for vegetarians. One cup (198 grams) of cooked lentils contains 6.6 mg, which is 37 percent of the RDI (16).

Legumes are also rich in folate, magnesium and potassium.

What’s more, studies have shown that beans and other legumes can reduce inflammation in people with diabetes. Legumes can also decrease heart disease risk for people with metabolic syndrome (17, 18, 19, 20).

Additionally, legumes may help you lose weight. They’re very high in soluble fiber, which can increase feelings of fullness and reduce calorie intake (21).

In one study, a high-fiber diet containing beans was shown to be as effective as a low-carb diet for weight loss (22).

In order to maximize iron absorption, consume legumes with foods high in vitamin C, such as tomatoes, greens or citrus fruits.

Bottom Line: One cup of cooked lentils provides 37 percent of the RDI for iron. Legumes are also high in folate, magnesium, potassium and fiber.

5. Red Meat

Red meat is satisfying and nutritious. A 3.5-ounce (100-gram) serving of ground beef contains 2.7 mg of iron, which is 15 percent of the RDI (23).

Meat is also rich in protein, zinc, selenium and several B-vitamins (24).

Researchers have suggested that iron deficiency may be less likely in people who eat meat, poultry and fish on a regular basis (25).

In fact, red meat is probably the single most easily accessible source of heme iron, potentially making it an important food for people who are prone to anemia.

In one study looking at changes in iron stores after aerobic exercise, women who consumed meat retained iron better than those who took iron supplements (26).

Bottom Line: One serving of ground beef contains 15 percent of the RDI for iron and is one of the most easily accessible sources of heme iron. It’s also rich in B vitamins, zinc, selenium and high-quality protein.

6. Pumpkin Seeds

Pumpkin seeds are a tasty, portable snack.

A 1-ounce (28-gram) serving of pumpkin seeds contains 4.2 mg of iron, which is 23 percent of the RDI (27).

In addition, pumpkin seeds are a good source of vitamin K, zinc and manganese. They’re also among the best sources of magnesium, which many people are deficient in (28).

A 28-gram serving contains 37 percent of the RDI for magnesium, which helps reduce the risk of insulin resistance, diabetes and depression (29, 30, 31).

Bottom Line: Pumpkin seeds provide 26 percent of the RDI for iron per serving. They are also a good source of several other nutrients and an excellent source of magnesium.

7. Quinoa

Quinoa is a popular grain known as a pseudocereal. One cup (185 grams) of cooked quinoa provides 2.8 mg of iron, which is 15 percent of the RDI (32).

Furthermore, quinoa contains no gluten, making it a good choice for people with celiac disease or other forms of gluten intolerance.

Quinoa is also higher in protein than many other grains, as well as rich in folate, magnesium, copper, manganese and many other nutrients.

In addition, quinoa has more antioxidant activity than other grains. Antioxidants help protect your cells from the damage done by free radicals, which are formed during metabolism and in response to stress (33, 34).

Bottom Line: Quinoa provides 15 percent of the RDI for iron per serving. It also contains no gluten and is high in protein, folate, minerals and antioxidants.

8. Turkey

Turkey meat is a healthy and delicious food. It’s also a good source of iron—especially dark turkey meat.

A 3.5-ounce (100-gram) portion of dark turkey meat has 2.3 mg of iron, which is 13 percent of the RDI (35).

In comparison, the same amount of white turkey meat contains only 1.3 mg (36).

Turkey also contains several B-vitamins and minerals, including 30 percent of the RDI for zinc and 58 percent of the RDI for selenium.

In addition, turkey contains an impressive 29 grams of protein per serving.

Consuming high-protein foods like turkey may help with weight loss, because protein makes you feel full and increases your metabolic rate after a meal (37, 38, 39).

High protein intake can also help prevent the muscle loss that occurs during weight loss and as part of the aging process (40, 41).

Bottom Line: Turkey provides 13 percent of the RDI for iron and is a good source of several vitamins and minerals. Its high protein content promotes fullness, increases metabolism and prevents muscle loss.

9. Broccoli

Broccoli is incredibly nutritious. A 1-cup (156-gram) serving of cooked broccoli contains 1 mg of iron, which is 6 percent of the RDI. This makes it a fairly good source (42).

What’s more, a serving of broccoli also contains 168 percent of the RDI for vitamin C, which helps your body absorb the iron better (8, 43).

In addition, this serving of broccoli is high in folate and provides 6 grams of fiber. It also contains vitamin K.

Broccoli is a member of the cruciferous vegetable family, which also includes cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, kale and cabbage.

Cruciferous vegetables contain indole, sulforaphane and glucosinolates, which are plant compounds believed to be protective against cancer (44, 45, 46, 47).

Bottom Line: One serving of broccoli provides 6 percent of the RDI for iron and is very high in vitamins C, K and folate. It may also help reduce cancer risk.

10. Tofu

Tofu is a soy-based food that’s popular among vegetarians and in some Asian countries.

A half-cup (126-gram) serving provides 3.6 mg of iron, which is 19 percent of the RDI (48).

Tofu is also a good source of thiamin and several minerals, including calcium, magnesium and selenium. In addition, it provides 20 grams of protein per serving.

Tofu also contains unique compounds called isoflavones, which have been linked to improved insulin sensitivity, a decreased risk of heart disease and relief from menopausal symptoms (49, 50).

Bottom Line: Tofu provides 19 percent of the RDI for iron per serving and is rich in protein and minerals. The isoflavones in it may improve heart health and relieve menopausal symptoms.

11. Dark Chocolate

Dark chocolate is incredibly delicious and nutritious.

A 1-ounce (28-gram) serving contains 3.3 mg of iron, which is 19 percent of the RDI (51).

This small serving also provides 25 percent of the RDI for copper and 16 percent of the RDI for magnesium.

In addition, it contains prebiotic fiber, which nourishes the friendly bacteria in your gut (52).

A study found that cocoa powder and dark chocolate had more antioxidant activity than powders and juices made from acai berries and blueberries (53).

Studies have also shown that chocolate has beneficial effects on cholesterol and may reduce your risk of heart attacks and strokes (54, 55, 56).

However, not all chocolate is created equal. It’s believed that compounds called flavanols are responsible for chocolate’s benefits and the flavanol content of dark chocolate is much higher than that of milk chocolate (57).

Therefore, it’s best to consume chocolate with a minimum of 70 percent cocoa to get the maximum benefits.

Bottom Line: A small serving of dark chocolate contains 19 percent of the RDI for iron, along with several minerals and prebiotic fiber that promotes gut health.

Iron is Incredibly Important

Iron is an important mineral that must be consumed regularly.

Yet it should be noted that some people need to limit their intake of red meat and other foods high in heme iron.

However, most people are easily able to regulate the amount they absorb from food.

Remember that if you don’t eat meat or fish, you can boost absorption by including a source of vitamin C when eating plant sources of iron.

This article was reposted from our media associate Authority Nutrition.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

These 10 Superfoods Can Help Balance Your Hormones and Reduce Inflammation

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe