By Bob Henson

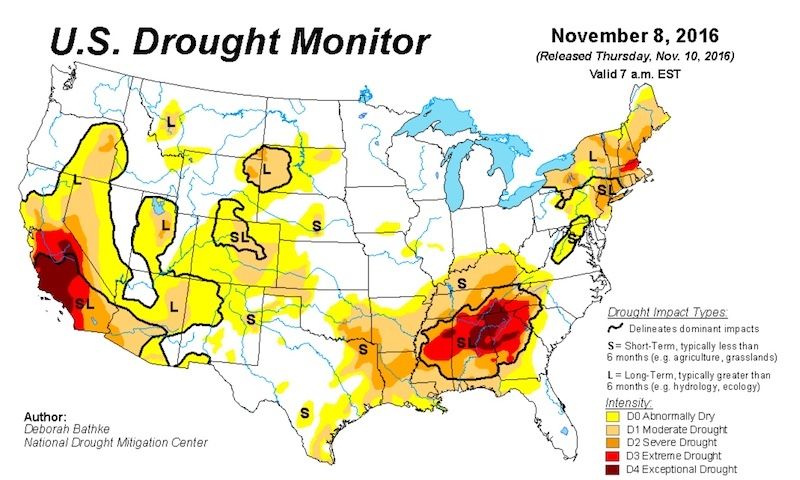

The atmospheric spigots have been turned off across most of the U.S. over the last several weeks. According to the weekly U.S. Drought Monitor report from Nov. 10, more than 27 percent of the contiguous U.S. has been enveloped by at least moderate drought (categories D1 through D4). This is the largest percentage value in more than a year, since late October 2015.

The upward trend of the last month is worrisome given the outlook for the coming winter: Drier-than-average conditions are projected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration across the southern half of the contiguous U.S., a frequent outcome during La Niña winters.

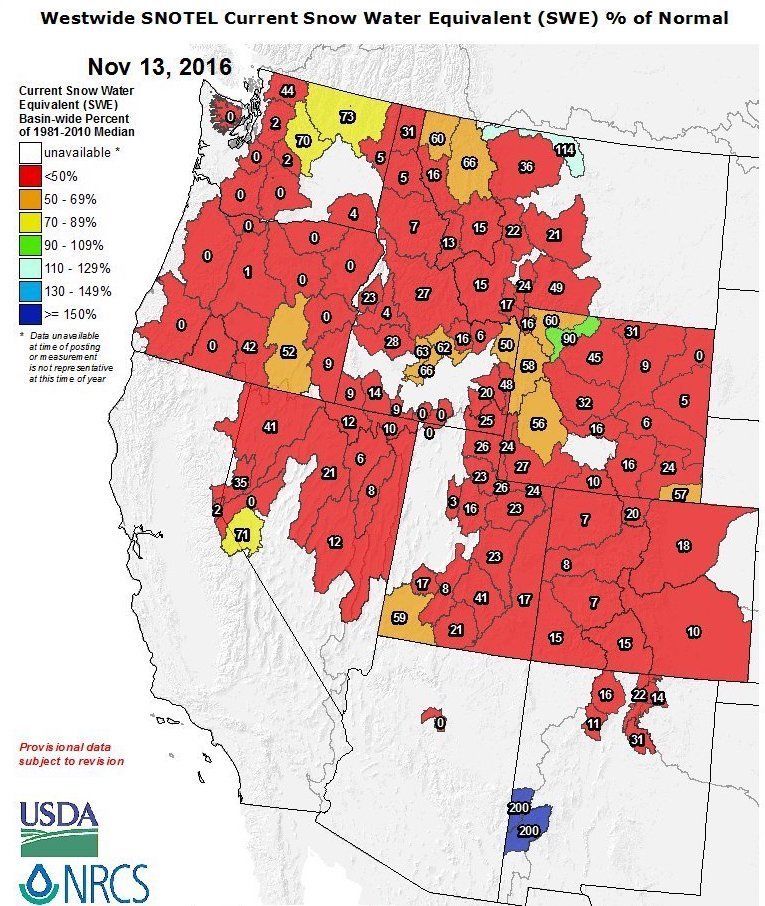

Where’s the Western Snow?

It’s common for parts of the mountainous U.S. West to take until late autumn or early winter to build up a proper snowpack, but such a delay seldom extends to the entire region. This month, nearly all of the high country of the Western U.S. is running far below the seasonal average for the amount of water held in snowpack. Ski areas are feeling the pain, especially since temperatures have rarely been cold enough this autumn for snowmaking to supplement nature. Several of Colorado’s major resorts have already postponed their opening dates, including Keystone, Breckenridge and Copper Mountain.

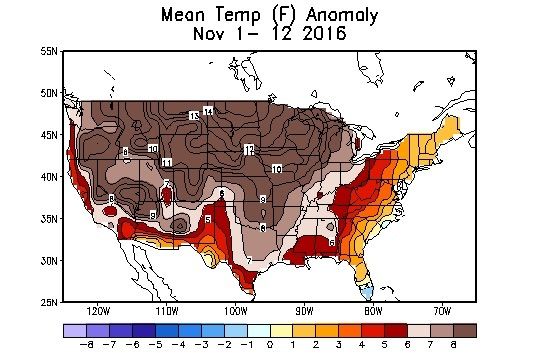

The paltry snowpack is especially striking in the Pacific Northwest, which just experienced its wettest October on record. Most of that precipitation came in the form of rain, leaving all but the highest mountains snow-free. “Still early in winter but snowpack is terrible,” tweeted Brad Udall, senior water and climate scientist at the Colorado Water Institute. Outside the Pacific Northwest, precipitation has been scanty and temperatures have been consistently warmer than average.

East of the mountains, the Plains and Midwest have been especially mild this month (see Figure 3 above). The Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport has yet to see a temperature below freezing, breaking the city’s all-time latest-freeze record of Nov. 7, 1900. La Crosse, Wisconsin and Peoria, Illinois, have also broken their latest-first-freeze records as they wait to dip to 32 F. All three locations should finally get a freeze this weekend in the wake of a potent storm system swinging across the central U.S. The storm will bring high winds and widespread snow to the northern Great Plains and Upper Midwest—perhaps a foot or more in parts of the Dakotas. The Central Plains could see an inch or so of rain, but prospects for rain further to the south and east are looking dim.

Weeks on End Without a Big Southeast Rain

It’s been more than a month since parts of the Southeast have seen a drop of measurable rain. Birmingham, Alabama, is on a record dry streak: 56 consecutive days without measurable rain as of Sunday, beating the previous record of 52 days set in 1924.

“Nine minutes of sprinkles Nov. 4 and another bout of sprinkles on Oct. 16 has been the entirety of Birmingham’s rainfall so far this fall,” observed Jon Erdman in a Weather.com roundup on Sunday. The most widespread rain since Hurricane Matthew in early October fell from eastern Georgia across northern South Carolina and southern North Carolina on Sunday, with widespread 0.5″ – 1.0″ amounts (Wilmington, North Carolina, picked up 1.77″). However, nearly all of the significant rain fell east of the drought-stricken areas. Assuming no major rainmakers arrive over the next couple of weeks—and none are on the horizon right now—large parts of the Southeast have a shot at their driest autumn on record (September-November).

In a region where rain is usually plentiful and frequent, a drought this prolonged has major consequences. In northwest Georgia, “our dirt is like talcum powder,” ranger Denise Croker (Georgia Forestry Commission) told Insurance Journal last week. Smoke from wildfires across the southern and central Appalachians has poured across the Southeast, especially where inversions have kept the smoke confined near the surface, as explained by Marshall Shepherd (University of Georgia) in Forbes.

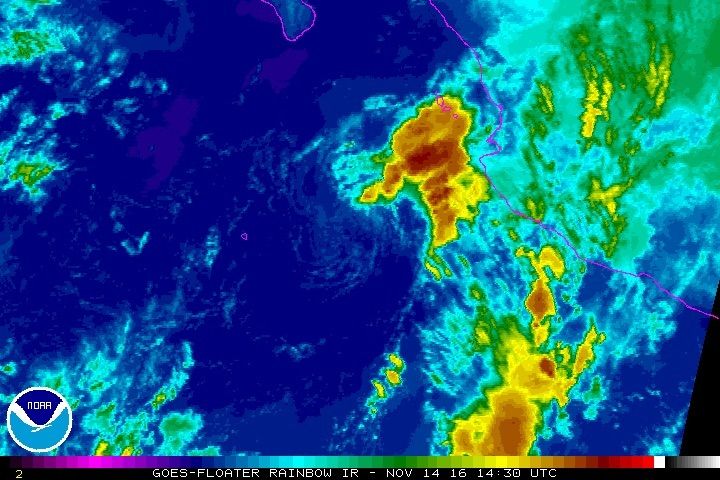

Tropical Storm Tina Pops Up and Fades Out in the East Pacific

A cluster of showers and thunderstorms gained just enough organization over warm waters (above 30 C) off Mexico’s Pacific coast to become Tropical Storm Tina on Sunday night. Tina was the 21st named storm of this year’s busy East Pacific hurricane season. Located about 200 miles west of Manzanillo, Mexico, Tina didn’t last long as a tropical storm. Christened at 11 p.m. EST Sunday with top sustained winds of just 40 mph, Tina was downgraded to a tropical depression at 10 a.m. EST Monday. High wind shear will continue to degrade Tina’s circulation as it decays into a remnant low by Tuesday, remaining well west of the Mexican coast.

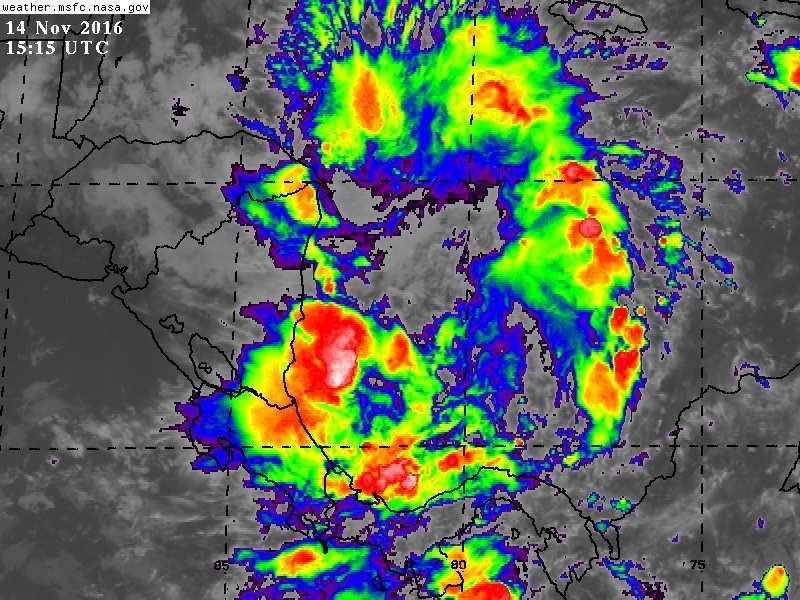

Potential Late-Season Tropical Cyclone in the Caribbean

Long-range computer models have suggested for several days that a broad circulation over the far southwest Caribbean east of Nicaragua might evolve into a tropical cyclone over the next week or two. Sea surface temperature remain very warm in the region: around 29 – 30 C, about 1 C above average for this time of year. In its latest Tropical Weather Outlook, issued at 7:00 a.m. EST Monday, the National Hurricane Center gives a near-zero chance of a tropical depression forming in this area by Wednesday morning, but a 60 percent chance by Saturday. Ensemble model runs from 00Z Monday provide support for the idea of very gradual development, with low odds of formation on any particular day but higher collective odds over a multi-day period. About a third of members of the ECMWF ensemble produce a tropical cyclone in the 3-5 day period (Wednesday to Friday night) and about half do so in the 6-10 day period. The GFS is more bullish, with nearly all of its ensemble members developing at least a tropical depression by the coming weekend. Steering currents will be extremely weak for some time, so any tropical cyclone that does develop could pose a threat for heavy rain if it lingers near the east coast of Central America.

Reposted with permission from our media associate Weather Underground.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe