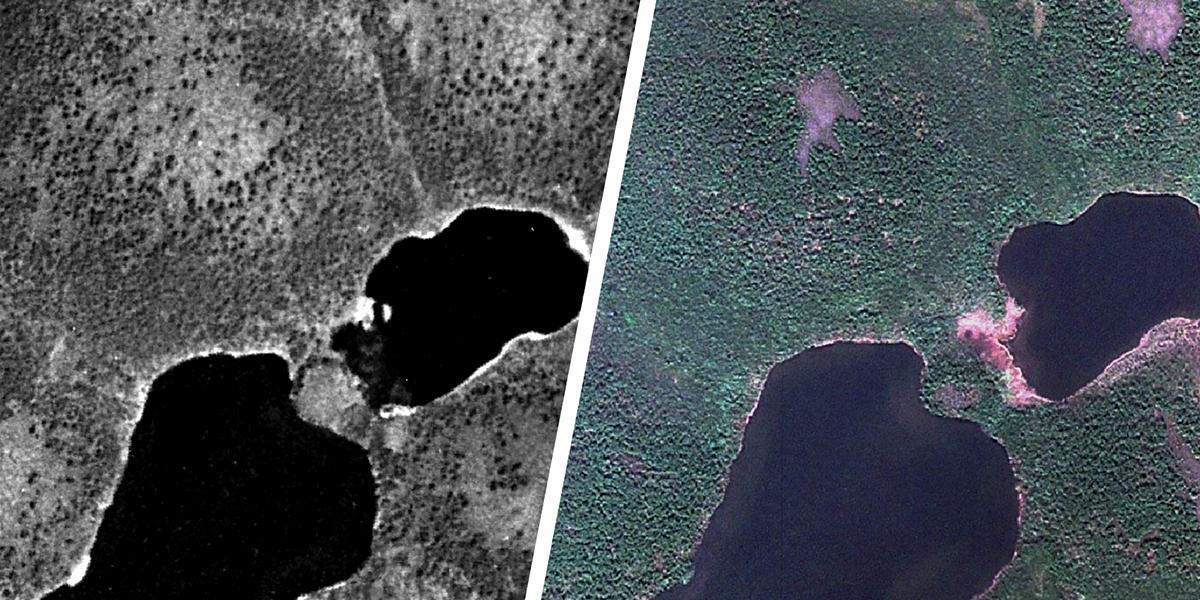

The recent declassification of tens of thousands of images from Cold War spy satellites is helping climate scientists compare Siberian terrain between then and now, and they’re showing some obvious signs of climate change.

It was common practice during the Cold War for the U.S. and Soviet Union to spy on each other using any means necessary, which included satellite and aircraft images from space to find military bases and possible signs of invasion. After the Soviet Union was broken apart, the U.S. released their images from Corona and Gambit, two reconnaissance satellites that were decommissioned in the 1980s.

The University of Virginia is now using those images to study the remote area of the Siberian tundra. By using images from current satellites, they are able to create a time lapse of the terrain. They found that the shrubbery and forested areas expanded by 26 percent since the 1960s images were taken.

“These spy images are a gold mine as a reference point,” said Howie Epstein, coauthor of the research. “We know from Earth-observing satellite data that the Arctic generally has been greening for 35 years or so. But the Siberian tundra had not been as closely observed until relatively recently.

“We now know that a lot of greening has been going on there, too, with tall shrubs and woody vegetation. The vegetation has been getting both taller and expanding in space and range.”

Though this may sound normal or even natural, Siberia has been widely affected by this expansion. Increased vegetation means an increase in carbon dioxide uptake or heat absorption, leading to a warmer regional climate and less snowfall overall. This has altered the ratio of plants to animals and affected the food web in the area.

To confirm their findings, the scientists traveled to the northern region of Russia to take samples. After gaining some insight on how the plants are spreading across the terrain, they were able to verify the dramatic changes. However, they also found that some areas have had a reverse effect and are actually browning. But there is still more research needed to understand this change of events.

“It’s clear that vegetation dynamics are more complex across tundra than previously thought,” said Epstein. “We still have a lot of work to do to understand Arctic changes and how this affects and is affected by changes to the global climate.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe