The most remote village on Earth, located on Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic Ocean, is about to get a 21st century upgrade thanks to an international design competition aimed at creating a more sustainable future for the farming and fishing community.

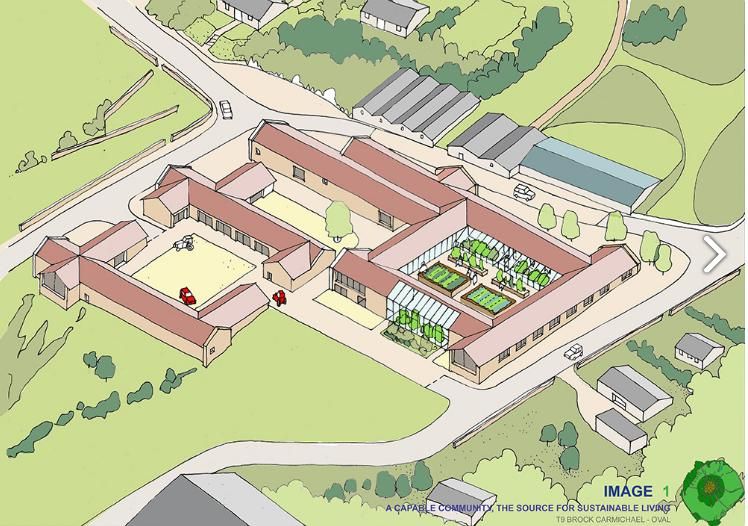

RIBA Competitions launched the competition in March 2015 on behalf of the Tristan da Cunha government and narrowed down the 37 anonymous entries from around the world to five teams. A little over a year later, the team led by Brock Carmichael Architects was identified as the winner of the competition because of its “practical approach and in-depth understanding of the issues.”

A wind farm, modernized buildings with heated floors and insulated roofs, greenhouses in backyards, communal kitchen gardens, community composting and a waste to energy incinerator are some of the improvements in the team’s initial plans for the 265-member community.

However, creating this sustainable community will be a challenge.

The island—located 1,750 miles (7 to 10 sailing days) southwest of Cape Town, South Africa—can only be accessed by sea on a passenger or cargo ship eight times a year due to the severity of the ocean swells and limitations of the harbor facility.

With the village so isolated, the main goal of this project is help create a self-sufficient community that future generations can manage themselves.

“Over a course of time, key people would be trained in any areas of expertise required to deliver these design proposals and acquire the knowledge and skills that can be passed down to generations to come,” Martin Watson, director of operations for Brock Carmichael Architects, said.

The main way Brock Carmichael Architects propose getting this done is to prototype materials and products found on the island—such as sheep wool, basaltic blocks and seaweed—to assess its performance in the exposed marine environment and build-ability using locally-trained labor.

Along the way, the Island Council will have the final say in what will be added to the final plans, and their goals are ambitious, wanting to produce 30 to 40 percent of their own energy within the next five years.

Brock Carmichael architects will head out to the island in summer 2017 to inspect the island before fleshing out more details in their designs.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe