By Diane Shohet

Earlier this month, Indonesian officials sounded the alarm that “haze” from forest fires was making its way towards neighboring Malaysia and Singapore.

Haze is a benign word for the toxic smog that swamps the region every year between August and October when smallholder farmers in Indonesia clear their old oil palm crops using traditional slash and burn methods.

Hearing the news took me back to last year’s fires, which were unlike anything the region had ever seen before and which I experienced first-hand, while living in Malaysia.

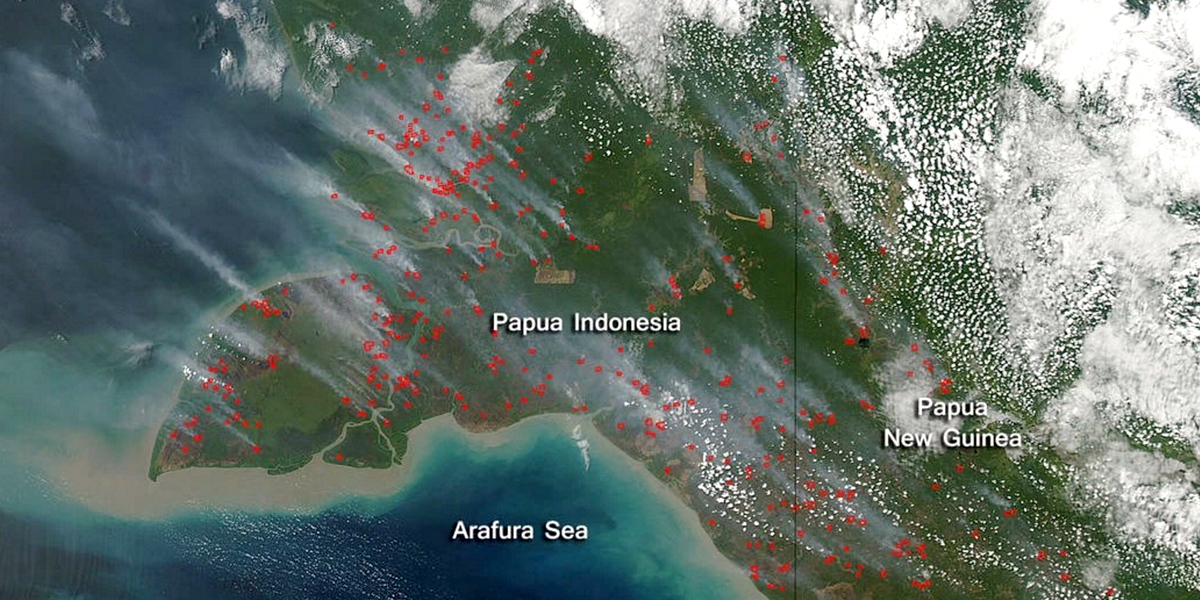

In 2015, dry El Nino conditions and drained peat bogs fueled these crop fires, causing them to quickly spread. From July to November, 2.6 million hectares of forest, peat and other land on the Indonesian islands Kalimantan (Borneo) and western Sumatra burned and a thick, toxic haze engulfed Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia.

By the time the worst of the fires were contained, financial damage to the region’s economy was estimated to be as high as $47bn. The human cost: an estimated 500,000 cases of respiratory tract infections and potentially more than 100,000 premature deaths. The 2015 Indonesian fires quietly became one of the largest ecological disasters in recent times and were labeled a “crime against humanity” by many.

A Personal Story

In 2013, my family moved from Boston, Massachusetts, to Penang, Malaysia. Before living in the area, we had little awareness of palm oil production. Our early drives through Malaysia provided our first glimpse: forests gone, hilltops cleared and dotted with new plantings, and hundreds of miles of palm oil plantations. A family trip to Borneo in search of its dense jungles and orangutans yielded an even more sobering reality: a five-hour drive across the interior of Borneo with only palm oil plantations to view.

In July 2015, we had been in the U.S., but returned to Penang in August. Visibility was low as haze from the fires in Indonesia descended on the city. Many people wore cotton masks that offered little protection from the fine particulate pollution. Our eyes watered and stung. The smell of smoke was everywhere. The Air Quality Index (AQI), a measure of pollution levels, was at an Unhealthy 150.

By mid-October, the AQI was a Very Unhealthy 250. During the previous weeks, millions of school children were unable to go outside. And finally, as AQI readings neared a Hazardous 300, schools throughout Malaysia were cancelled. Many businesses temporarily closed as they are located in open-air structures, the mainstay of tropical climates. Airports shut down or restricted flights.

During the third week of October, I was forced to go to the hospital. Unable to breathe, I was put on a nebulizer, an inhaler and other drugs. A 45-year old doctor who had lived her entire life in Penang and who had been seeing an influx of respitory infections, stated, “I have never seen the haze as bad as it is.”

In Riau, Indonesia, during this same week in October, the AQI in the region rose above 1,000 for over a week while visibility fell below 100 meters. All babies under six months of age were evacuated.

Like millions of other mothers throughout Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia, I now wonder about the health of my child. How will exposure to months of toxic pollution affect him? And, how can we keep this type of environmental disaster from happening again?

First, some background on the drivers of this disaster.

The Palm Oil Story

Globally, we crave palm oil. It is found in 1 in 10 food products and up to 50 percent of household products in countries like the U.S. and Canada. It is used for soaps, cosmetics, plastics, detergents, biofuels and much more. In 2013, 58 million tons of palm oil was produced.

Almost all the world’s palm oil—85 percent—is produced from the fruit of the oil palm in just two countries: Indonesia and Malaysia. Currently, in Indonesia, 10 million hectares of palm are under cultivation and that is projected to grow to 13 million by 2020. Between 2009-2011, 25 percent of all forestland in Indonesia was cleared to plant oil palms. While restrictions on deforestation exist, Indonesia is clearing its forests faster than any other tropical nation.

And it is not just tropical forest being cleared, peat land forest is being cleared and drained. When each hectare of peat land is cleared for oil palm production, 3,750-5,400 tons of carbon dioxide is released over 25 years, making Indonesia the third largest greenhouse gas emitter after China and the U.S., before the 2015 fires.

On many days in September and October 2015, in fact, the CO2 emissions from the fires in Indonesia exceeded the daily average emitted by the U.S. In fact, in those two months alone, the fires released more CO2 than what Germany emits in a year.

The Indonesian government is stepping up efforts to control the spread of the fires this year, but what can we do to get to the root of the problem?

The Future

Efforts to stop the deforestation include the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a multi-stakeholder organization founded in 2004, that provides third-party certification of sustainable palm oil production. Some major brands and investors don’t think it goes far enough, however, and have urged RSPO to adopt stricter guidelines and more robust enforcement protocols. In 2013, in fact, a wave of companies adopted groundbreaking “no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation” commitments to supplement the certification scheme.

Indonesia has also placed a moratorium on issuing new clearing permits until 2017; however, previous moratoriums only slightly slowed deforestation.

There are key barriers to sustainability: Government corruption is rampant in Indonesia and corporate corruption can flourish when there is little regulation or oversight. Add to that a lack of support for smallholder farmers who often continue to rely on slash-and-burn farming techniques.

Many rely on palm oil for their livelihoods in Indonesia where 28.6 million still live below the poverty line and approximately 40 percent of all people live just above the national poverty line. So, this story needs to end with sustainable palm production, and that means supporting livelihoods in Indonesia and protecting the environment in the context of growing international demand for palm oil.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe