By Meg Wilcox

Just north of Denver lies Colorado’s most productive agricultural region, Weld County. Its rolling hills, grasslands and South Platte River system provide fertile ground for dairy cows, beef cattle, corn, sugar beets and forage crops.

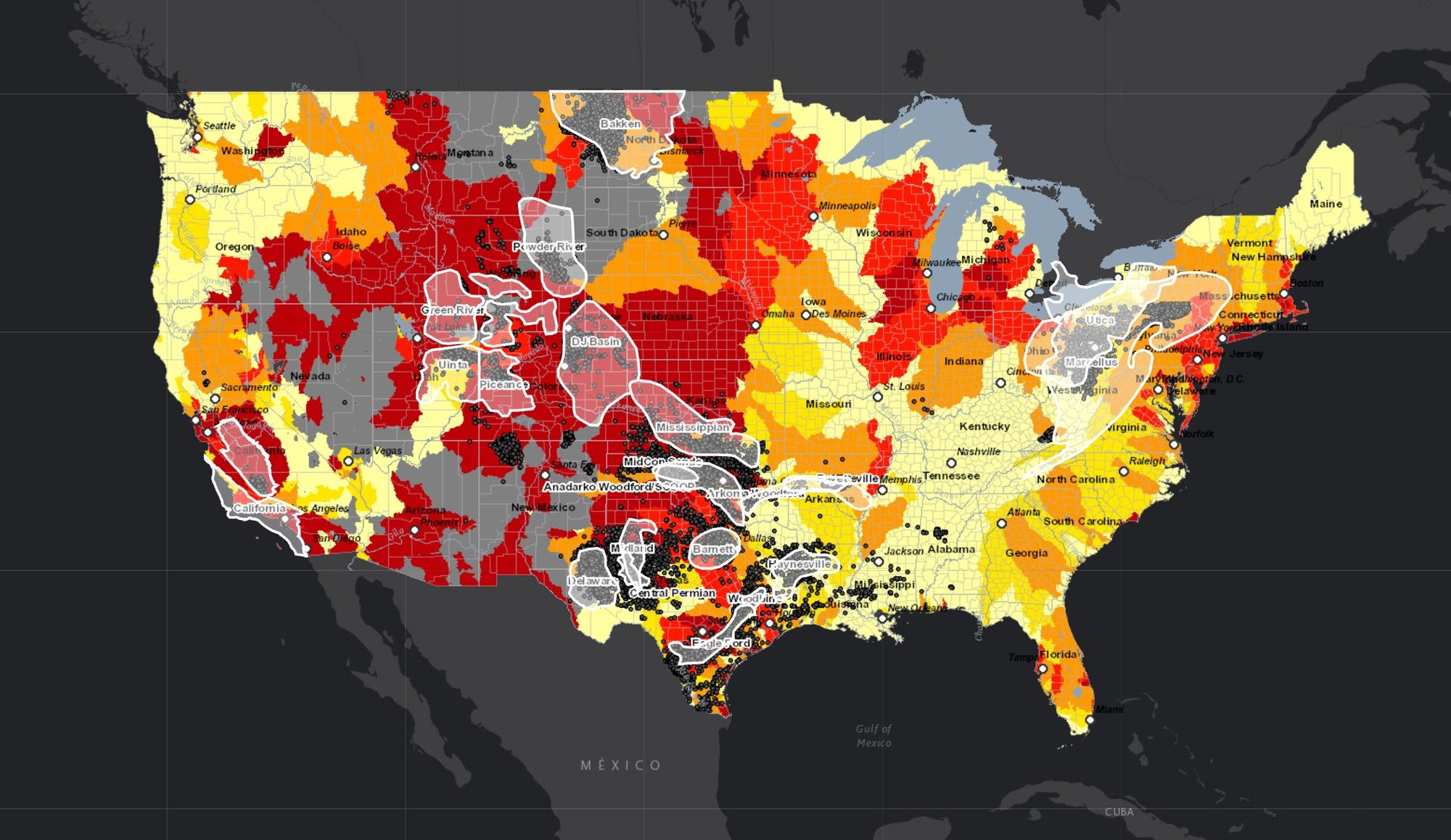

But Weld County also sits on top of the Niobrara (DJ Basin) shale formation and that makes it the number one hotspot in the U.S. for new hydraulic fracturing activity. Over the past five years, close to 7,000 wells were drilled within its 3,996 square-mile area.

Among the myriad impacts of fracking on county residents is stress on their water supply. To recover the natural gas unevenly distributed throughout the shale formation, the hydraulic fracturing process blasts large volumes of water, fine sand and chemicals into the ground to crack open the formations.

Weld County’s nearly 7,000 fracking wells, in fact, used 16 billion gallons of water over the past five years, more than any other county in the U.S., according to new research by Ceres. And that’s a concern because Weld County is a region with extremely high water stress, according to the World Resources Institute Aqueduct Map. Extremely high water stress means that more than 80 percent of the county’s available water resources are already allocated for municipal, industrial and agricultural uses.

Weld County is not alone. Fracking activity throughout the arid south and west is placing increasing pressure on ever-tighter water supplies, with Colorado and Texas being ground zero.

Ceres researchers mapped water use in hydraulic fracturing across the U.S., using data from FracFocus.org and the World Resources Institute, and found that 57 percent of hydraulically fractured oil and gas wells between Jan. 1, 2011 and Jan. 1, 2016 were in regions of high water competition.

Our newly released interactive map shows water use by shale play and operator. Check it out:

Among our key findings:

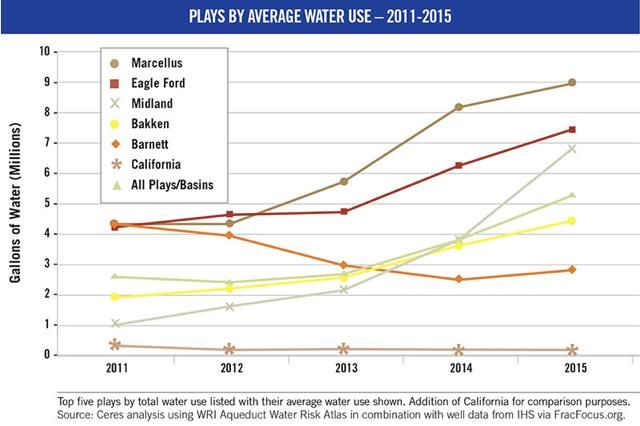

- The top three shale plays by water use were the Eagle Ford in Texas, Marcellus in Pennsylvania and Midland Plays in Texas, with the Eagle Ford and Midland Plays being of particular concern given both their high water use and exposure to high water stress, drought and declining groundwater supplies.

- Chesapeake, EOG Resources and Anadarko Petroleum were the biggest water users overall, while Pioneer Natural Resources and Encana were especially active in regions with extremely high water stress.

- A total of 358 billion gallons of water was used for hydraulic fracturing over the 5-year timeframe, equivalent to the annual water needs of 200 mid-sized cities.

- While overall fracking-related water use peaked in 2014 along with the slowdown in oil and gas production and plummeting prices, average water use per well doubled since 2013, from 2.6 million gallons per well to 5.3 million gallons per well at the end of Jan. 2016. This is likely due to modifications in drill site activity.

Even though oil and gas production have slowed, local communities at the epicenter of fracking—many in the country’s most water-stressed regions—still face significant long-term water sourcing risks.

Our research found that, in seven of the top 10 counties for fracking activity, annual water use for hydraulic fracturing reached more than 100 percent of each county’s domestic water use.

That high level of demand for water from shale production companies can potentially drive up the price of water for everyone else, or make supplies harder to come by.

Several years ago, for example, Kent Peppler, a fourth-generation Weld County farmer, told The Associated Press that he was fallowing some of his corn fields that year because he couldn’t afford to irrigate the land for the full growing season, in part because energy companies were driving up the price of water.

“There is a new player for water, which is oil and gas,” Peppler said. “And certainly they are in a position to pay a whole lot more than we are.”

Local communities also face the issue of wastewater disposal, with its potential impacts on drinking water supplies and earthquake activity. The enormous volumes of wastewater produced by hydraulic fracturing are disposed of in underground deep well injection sites, which has been linked to both surface and groundwater contamination and to earthquakes.

It's Official: Injection of Fracking Wastewater Caused Kansas’ Biggest Earthquake https://t.co/nvk4stRwC0 @Frack_Off @Peter_Seeger

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) October 15, 2016

But the companies themselves face long-term water sourcing risks in these regions with high water stress, as well as an emerging regulatory risk related to wastewater disposal. Oklahoma, for example recently ordered the shut down of 37 wastewater disposal wells after a 5.6-magnitude earthquake struck the state.

Investors with oil and gas companies in their portfolios are taking note. As Steven Heim, managing director for Boston Common Asset Management, recently put it, “Hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas extraction, which used to be ‘unconventional,’ is now a part of most conventional energy company portfolios in the U.S. and Canada. This has made water management a critical liability or competitive advantage for companies and their investors.”

There are certain operational practices and other steps that oil and gas companies can take to lessen their water impacts and lower their risks. For example, shale operators can consult with local communities on water needs and wastewater plans before starting operations, collaborate with industry peers and other industries on local water sourcing challenges and develop local source water protection plans. You can find a full list of our recommendations here.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe