Colorado had quite a year in 2013. Aside from record setting forest fires, warming temperatures and continued pine beetle infestations, Colorado had a storm in September, typically our dryest month of the year, that has been referred to as a 100 year to a 500 year to even a thousand year flood. Whatever the case, it was a big, big flood with lots and lots of rain, around 17 inches of rain equivalent to around 20 feet of snow.

on September 13, 2013. Photo credit: The Denver Channel

Shane Davis, a person who feels strongly about fracking and flooding, took some time out of his busy day to talk with me for this EcoWatch exclusive interview. For all of you who don’t know Shane Davis, let me introduce him to you. He is an interesting guy. For starters, his boyhood found him living on the border of Canada and northern Idaho. This put him into the natural world from the very beginning. He’d say he’s been an activist concerned for the environment since the age of seven or eight when he became fully aware of the environment. He had an innate response to the environment. Davis comes equipped with much experience. He was a park ranger for many years, helping create stewards of the natural world as an “interpreter naturalist.”

He worked for the Colorado State Parks, Department of Natural Resources and in the South Pacific as a marine biologist for NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Davis is a biologist by training. He is a guy with a vast yearning for discovery. He initially focused on biology in college and then switched to molecular genetics, being a National Science Foundation grant recipient in this area. He also received a NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) medal for his work oversees managing an environmental safety and security pilot program.

Davis became interested in fracking more than four years ago while living in Firestone, CO. He helped start the first grassroots organization for anti-fracking in Colorado in mid 2010, and created the website Fractivist.com that

Fracking is a practice that has been used by the oil and gas industry for quite sometime. However its use has been becoming much more sophisticated and escalating at a significant proportion in recent times as oil and gas deposits have been getting scarcer and the exemptions of the 2005 Energy Policy Act kicked in.

Fracking releases oil and gas deposits by drilling down often to depths of two miles or greater and then, in more recent times, horizontally. In Colorado’s Wattenberg oil field in the Denver-Julesburg Basin the current target depths are 7,000 to deeper than 8,000 feet. Injecting water and chemicals at pressure creates a multitude of fractures in the surrounding rock releasing the trapped oil and gas. For a typical well two to four million gallons of water is used. Four to five, or even up to nine, million gallons of water can be used in a horizontal well.

The wastewater mixed with toxic chemicals gets pumped out and often injected into auxiliary holding wells and capped. The oil and gas is released and moves up the well. Many people living near the well sites voice concern and examples of harm to their health, while the general industry stance appears to say that the fracking process is entirely safe and free of harm to people and the environment.

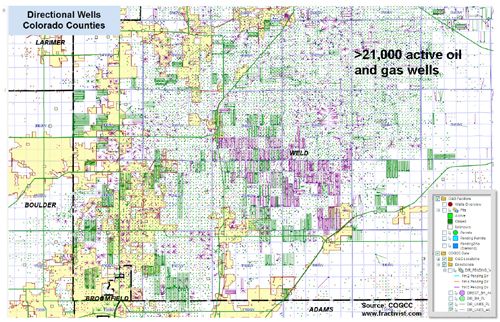

There are about 51,000 active gas wells in Colorado, and 79,000 inactive wells—50-55 percent of these are awaiting the new fracking technology. So approximately 130,000 completed wells exist in Colorado. Weld County amazingly has about 21,000 active wells, more than in any other Colorado county or any other county in the U.S.

MS: Is fracking safe?

SD: Absolutely not. It never will be.

MS: Is using our water worth it for going after oil and gas?

SD: I am absolutely appalled that the oil and gas industry is using our most valuable resource—water—to mine for something far less valuable.

MS: Why are you passionate about preventing fracking?

SD: I think, number one, is to protect the health and safety and welfare of the environment and citizens from the adverse impacts—the very harmful impacts of the fracking process and the drilling … just everything the oil and gas extraction industry encompasses. But I think even more so, we are so much more smarter, yet extracting yet another fossil fuel. I firmly believe we are going down, backwards. We need to go forward, and have research and development that focuses solely on healthy energies that allows the U.S. to have healthy energy democracy not an extractive oligarchic sort of energy island. Seriously, an oil-garchy is what we call it. We are just going in the wrong direction to serious consequences.

MS: Why should we be concerned about fracking?

SD: Well I think in short why the citizens of America or the globe should be concerned about fracking is that it’s a largely unregulated industry that is not for the benefit of energy democracy in America or the health and welfare of the people, and it’s for the less than 1 percent, and it’s extremely damaging, it’s environmental catastrophe waiting to happen decades from now and human health catastrophe.

A tremendous amount of rain fell down upon Colorado the week of Sept. 9. On Sept. 16, Boulder County gauged a record setting 17 inches of rain. The average yearly precipitation for this county is 20.7 inches and for the month of September 1.7 inches. It is the heaviest recorded rainfall Colorado has seen. If snow fell instead of rain, the Front Range would have been buried by some 20 feet of snow.

While the rain that is responsible for the Big Thompson Canyon flood of 1976 was extremely localized and a rapid downpour, where eight inches fell in the first hour and 12 inches total in the first three hours, Colorado’s September flood waters spread over a vast 2,000 square mile area affecting 17 counties from north to south along the Front Range.

At Governor Hickenlooper’s request, President Obama, on Sept. 12, declared a state of emergency in Boulder, El Paso and Larimer counties, and 12 more counties were added Sept. 16 (Adams, Arapahoe, Broomfield, Clear Creek, Denver, Fremont, Jefferson, Morgan, Logan, Pueblo, Washington and Weld). According to COGCC (Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission), 1,970 active wells were affected by the flood waters with drums tipped over, failure of oil lines and containment facilities, and other equipment damaged. As of the latest Nov. 26 report, 14 confirmed spills occurred spilling 48,250 gallons of oil and indicating the release of 43,479 gallons of produced water (basically toxic liquid industrial waste).

COGCC has admitted that historically 43 percent of oil and gas well spills prior to the flood, in Weld County, resulted in groundwater contamination. Produced water is exposed in open pits and mix readily with the flood waters. Much concern has been raised over the safety of such drilling operations in flood situations.

“Fracking and operating oil and gas facilities in flood plains is extremely risky,” said Clean Water Action’s Gary Wockner. “Flood waters can topple facilities and spread oil, gas and cancer-causing fracking chemicals across vast landscapes making contamination and clean-up efforts exponentially worse and more complicated.”

As reported by the Daily Camera, “Lafayette-based anti-fracking activist Clif Willmeng said he spent two days ‘zig-zagging’ across Weld and Boulder counties documenting flooded drilling sites, mostly along the drainage-way of the St. Vrain River. He observed “hundreds” of wells that were inundated. He also saw many condensate tanks that hold waste materials from fracking at odd angles or even over turned.”

MS: What happened during the flood?

SD: The flood in September was a shocker, not just to Colorado, but the United States and the world that Colorado had its first tropical rainstorm. About 1,970, according to the state, active oil and gas well pads were negatively impacted by the flood as well. The amount of rain that fell was unprecedented. It was an epic flood of epic proportions. And it paved its way through the highest density of active producing well pads in Colorado and the United States. So, it was a shock to the industry and to the people. There were so many people that lost their homes, which is the saddest part of all. So, what we saw here were worst case scenarios, which the state and industry were not prepared for.

MS: Could you tell me what you did during/shortly after the flooding?

SD: I went up into the air five times. I flew over the flood plain from Boulder to nearly the Nebraska border five separate times. I took up CNN, NBC, NPR, New York Times, all kinds of people out into the field, on the ground and in the air. Took several thousand photographs of the well pads that were impacted negatively where you could see the condensate or crude oil tanks or produced water tanks flipped over, pipes broken. So basically what I did was taking maybe three or four dozen people out on the ground and up in the air to show the leading media across the nation what really happened.

MS: What would you say was the most common damage?

SD: I think the most common damage people saw on the surface, was the tanks listing or flipped over on their sides or floating down this new epic river. But one thing I tried to show case was the subsurface infrastructure. The industry and the state were only talking about the equipment that was on top of the ground. And I know being on the ground the floods were so strong they washed away three and four and five feet of top soil in many areas along the river—the South Platte and St. Vrain River. And so what I looked at was these subsurface infrastructure to include flow lines, gathering lines, all the plastic pipelines that carry the petrochemicals to and from the production sites to the gathering stations to the refineries. Just like the Titanic, the Titanic was not sunk from the tip on the iceberg. It was the subsurface infrastructure that caused the most amount of damage. So that was my talking point because the industry can say we sucked up this amount of crude oil, this amount of produced water on the surface that spilled but what they are not telling us is what they don’t know which lies beneath the surface. They don’t know how much of those chemicals are still leaking because they’ll have to inspect every inch of those flow lines and those gathering lines all across the flood plain.

MS: And what would you say are the main types of contamination that especially you’re most concerned about that was released?

SD: Well all of it. Obviously crude oil which is also considered condensate. It’s crude oil but it has a number of other fluids, toxic or endocrine disrupting chemicals that would be mixed in with it until it would be refined or before it was refined. Also, any of the fracking fluid constituents to include naturally occurring radioactive materials that come up from the well bore that are stored in the produced water vaults. So I think it’s everything. I don’t have one in particular. Anything that is not naturally on the surface that is a product of oil and gas that spills on the surface that contaminates the surface is a problem.

A lot of these chemicals people need to know are endocrine disrupting chemicals that are so damaging to our reproductive systems, short term, long term and forever. Any and all of these chemicals that were released is a problem. The oil and gas industry is saying, well there is only a small amount of these chemicals released. That is the problem. And again the industry is saying, “dilution is the solution to pollution.” Well they can’t have that as a best management practice. And that’s what they are relying on all the time … when you say, “dilution is the solution to pollution.” For example, basically these open evaporation pits on western slope like in Garfield County where hundreds of millions of gallons of toxic industrial liquid waste are being evaporated into the air from the industry’s backyard to your backyard. And the same thing applies when you have huge spills like this, well it spilled into the water so it was diluted. This is our water. These waters of the state. The people’s water. This should never happen. The industry should be held extremely accountable for their actions.

Davis clarified at another point in this interview that the main contaminants to be especially concerned about are Benzene, Ethylbenzene, Toluene and Zylene, which are called BTEX chemicals. There is also Methyl Chloride (extremely dangerous), Cyclopentane and dozens of other chemicals released. A common batch of fracking fluid could hold 500 or more different ingredients that is currently not required to be disclosed to the general public or the government.

MS: What should we do in the future with fracking?

SD: Well outside of banning it completely, I think that in the interim while we can figure how to ban it there should be an enormous severance tax to research and development for the state in which it’s conducted. I also believe money should be set aside, millions and millions of dollars for environmental remediation and any associated health impacts.

They have a bond. Every operator has a surface bond and a surface agreement, a land use agreement, with the private land owner or state or federal mineral holder rights. But their bond is anywhere from two to 25 thousand dollars. And just simple remediation of a well pad—let’s say there was a thousand barrels of oil that spilled on the surface, just the remediation if that was in an agricultural area which 90 percent of all oil and gas wells are in Weld County, they are right in the center of an Agriculture area—the bond they put up, the two to 25 thousand dollars, doesn’t even begin to start the remediation. So, the fines and the bonds are so outdated that they don’t cover actual/factual costs. We need to envision something that is going to remediate the damage that the oil and gas industry imposes on our ways of life. And let us not forget that the federal exemptions, that the oil and gas industry currently lavishes in, strips our civil rights and protections. Now the citizens, free citizens of America cannot protect themselves from the adverse impacts of the fracking processes—to include the development, the drilling, the fracking, the production, the transportation.

Active wells are supposed to get inspected every year, and inactive every five years. That’s the rules and regulations right now. But the inactive are as problematic as the active … if not more so. I absolutely believe the abandoned wells should be inspected (if they are not) twice per year especially in the winter [they experience a lot of contraction and expansion].” Colorado has 13 field inspectors and about four that sit at a desk directing the field inspectors. These people are staffed through COGCC, which is state funded.

There has been a lot of activity, especially in local Colorado communities, fighting for a ban on fracking. Longmont voted for a ban in 2012 that was challenged by the oil and gas industry organization (COGA) and the state (COGCC). In the Nov. 5 election, Fort Collins, Boulder, Lafayette and Broomfield had moratorium/banning initiatives on their ballots.

“It’s amazing, every time there is a public meeting, more people show up than the last time,” said Russell Mendell, state organizer for Frack Free Colorado in The Daily Camera. “And it just seems like people are starting to be educated on the issue, and more and more people are showing they are passionate about protecting the community from the impacts of fracking. It represents the citizen movement that has been really sort of spreading across Colorado and across the country as well, as people learn about the health impacts of fracking, the impacts on home values, the impacts to so many different elements of people’s lives including the economy, and the tourism economy and to local business.”

MS: Could you give me an update on the local initiatives of the last election and the US House legislation vote?

SD: Fort Collins has a five year moratorium [passed with 55 percent]. Longmont we know they are obviously being sued. They had a 60 to 40 [passed] initiative which is a ban on fracking. Boulder has a five year moratorium in which more than 70 percent voted in favor of it. Lafayette has [by 58 percent] a Community Bill of Rights ban which is extremely unique in that the Community Bill of Rights ban is just not for fracking but trumps corporate rights. It says, “Community rights now preempt corporate rights.” That one is extremely symbolic for Colorado. And Broomfield just recently passed their moratorium with [17] votes … Loveland was going to be number five that took a really weird turn. Loveland was set to have a two year moratorium put on the ballot and this city council found a loophole in their local policy that stripped the voters’ rights to be able to put the two year moratorium on the ballot.

MS: How would you interpret the results in what happened with Boulder, Broomfield, Fort Collins, Lafayette, Longmont and regards to the U.S. House/FRAC Act related voting?

SD: I interpret the results as the voice or courts of public opinion. Colorado people have spoken. They’re concerned citizens for the health and welfare of their families and the environment. What you’re seeing is this is a civil rights movement right now. It’s no longer truly just about hydraulic fracturing. It’s taking on this new life of civil rights movement because right now Colorado Oil and Gas Association (COGA), is now suing Longmont, they’re suing Fort Collins and they’re suing Lafayette, and they’ll probably sue Broomfield as well. But suing because we enacted and demonstrated our democratic vote tells me that there is something substantially wrong with our political environment today. If COGA, the oil and gas industry’s mouthpiece, is suing to take away our democracy and our votes, that’s absolutely unconstitutional and a violation of our civil rights. So, I think what you’re seeing is the general public becoming more aware not just of the hazards of hydraulic fracturing but how the industry, the oil and gas industry, is marginalizing and suing to take away our rights.

MS: Still on the horizon is the FRAC Act (Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act), which has been reintroduced each Congress since 2008 by Diana DeGette (D-CO). Maurice Hinchey (D-NY) has co-sponsored with DeGette and more recently Congressman Jared Polis (D-CO). In 2013, for the first time, the bill was introduced as a bipartisan measure with Chris Gibson (R-NY). Nevertheless, the U.S. House knocked out the FRAC Act once again during this Congressional session.

The FRAC Act establishes common sense safeguards to protect groundwater, requires disclosure of the chemicals used in fracking fluids and removes the oil and gas industry’s exemption from the Safe Drinking Water Act, the provision added to the Energy Policy Act of 2005. The lobbying group Energy in Depth said the FRAC Act is an “unnecessary financial burden on a single small-business industry, American oil and natural gas producers,” and claims enacting new regulation could result in half of the U.S. oil wells and one third of the gas wells being closed. Congressman Hinchey said, “We need to know exactly what chemicals are being injected into the ground and we must ensure that the industry is not exempt from basic environmental safeguards like the Safe Drinking Water Act.”

Can you share your thoughts on the FRAC Act?

SD: It’s gaining a lot more nationwide illumination. And the activists around the nation are trying to rally around the FRAC Act, the Breather Act. Those are to essentially overturn the federal exemptions in the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Water Act. The industry is exempt as you know from key provisions in those federal laws. And so Jared and Diana DeGette’s FRAC Act would actually overturn those exemptions for water. Right now the water and chemicals the industry are putting down the bore hole are not considered hazardous materials—that’s their exemption. I don’t know where it stands now but I know they are fighting tooth and nail. Diane DeGette is a champion for us. But she really has to continue through. I know it’s a good act, that needs to happen. Like all the 2005 Energy Policy Act exemptions for the industry, all of them need to be overturned. And so the FRAC Act and Breather Act are parts and pieces of the whole that we need to pursue.

The anti-fracking successes in the last local election in Colorado and the continued, now bipartisan, efforts to pass the FRAC Act are signs of how the fight against fracking is trending in Colorado and elsewhere. However, former Republican Colorado State House Rep. B.J. Nikkel is quoted as saying about the Colorado election results: “This is round one of a much longer match.”

The oil and gas industry is likely to do similar things as they did in Longmont. This stems from interpreting the current rules overseeing fracking as placing the authority at the state level. The argument can be had that local municipalities do not have the right to govern the banning of fracking.

Pro-fracking advocate Tisha Schuller, president of the COGA, argues that the Boulder and Lafayette bans are merely symbolic because “Lafayette’s last new well permit was in the early 1990s and Boulder’s last oil and gas well was plugged in 1999.” It appears likely that COGA will go after the Fort Collins and Broomfield with their more heavily producing areas in similar fashion (and perhaps Lafayette) as how they’re suing to stop the Longmont ban.

Overall Davis thinks the recent election shows a hopeful sign that the escalating use of fracking will slow and be subjected to more thoughtful watchful scrutiny and regulation. Nikkel sees things differently, saying “As the debate moves from places like Boulder and Lafayette—which come with highly Democratic constituencies—to purple Colorado, you’re going to see a different outcome.”

Davis is hopeful that the state of Colorado will be able to generate a fund (perhaps in the likes of a Superfund that handles hazardous waste sites) to help inspect, monitor and remediate active and closed oil and gas wells. He is hopeful that the State will get more than the 13 field and four office inspectors that they currently have to inspect the some 51,000 active wells in Colorado and nearly 79,000 abandoned/inactive wells.

Michael Sobczak is a writer living in Boulder, CO at the base of the Rocky Mountains with a strong interest in environmental issues both locally and those surrounding us.

Visit EcoWatch’s FRACKING page for more related news on this topic.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe