Why Pruitt’s ‘Cooperative Federalism’ Spells Trouble for Clean Water Protection

By Brooke Barton

A majority of Americans value strong federal protections for clean air and water, which provide both environmental and economic benefits.

But they should be very worried that the basic human expectations of healthy air and safe water will quickly turn cloudy if the new U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator’s pledge to regulate through “cooperative federalism” becomes a reality.

https://www.facebook.com/EcoWatch/videos/1460041177342148/

Cooperative federalism, at its most benign, is about allowing each state to tailor its own approach to enforcing environmental rules. At its worst, it’s about the federal government turning a blind eye to states that shirk the nation’s environmental laws or that simply don’t have the coffers to pay for monitoring and enforcement.

“Process, rule of law and cooperative federalism, that is going to be the heart of how we do business at the EPA,” said EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, who has promised to follow the Trump administration’s will to slash EPA’s budget and soften its rules.

To see how cooperative federalism erodes environmental protection, look no further than the 2015 Waters of the United States rule. President Trump issued an executive order last week announcing plans to undo the rule, which clarifies the federal government’s authority to limit pollution in bodies of water not explicitly covered by the Clean Water Act.

Interactive Map Shows if Your Drinking Water Is at Risk From Trump's Executive Order https://t.co/tnV4CwKmaq (via @EcoWatch @ewg)

— Sierra Club (@SierraClub) March 5, 2017

Those smaller bodies of water—typically streams, wetlands and rivers, which account for more than half of the nation’s freshwater resources—feed into larger water bodies that provide key drinking water and recreational opportunities for the public, as well as water supplies for business. Keeping them clean is vital for the nation’s health and economic prosperity.

The executive order, coupled with the administration’s penchant for cooperative federalism, send a strong message that if states choose not to protect smaller streams and wetlands, they won’t get pushback from the federal government.

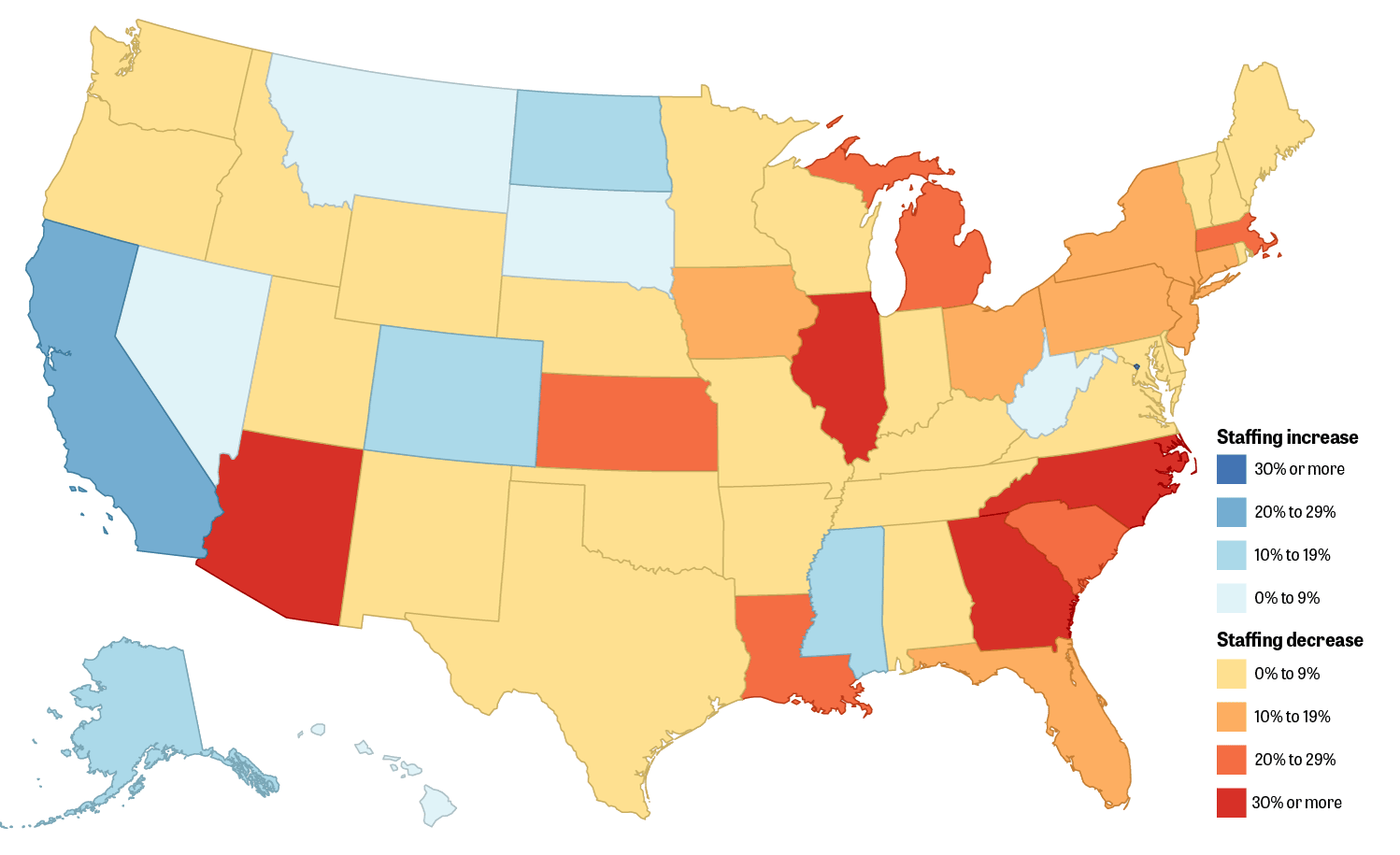

And as state environmental budgets shrink, many simply don’t have the resources to ensure healthy streams and clean drinking water on their own, even if they wanted to. Forty state environmental agencies have reduced staff in recent years, with the biggest cuts being in North Carolina, Florida, Michigan, New York, Illinois and Arizona, according to a fall 2016 report by the Center for Public Integrity.

Pruitt’s home state, Oklahoma, for example, spends a paltry $13 million on environmental protection. Compare that to Connecticut, which has an environmental budget twice the size of Oklahoma’s but less than one-tenth the land mass or with neighboring Arkansas, with a budget nearly triple the size of Oklahoma’s.

Water pollution from industrial-sized poultry farms operating in the northeast corner of Oklahoma and in neighboring Arkansas, has been a source of huge controversy, health concerns and lawsuits for more than 25 years. Phosphorus, the primary pollutant in poultry manure, can trigger toxic algae blooms, threatening rivers, lakes and other waterways that feed into the Illinois River.

Cooperative federalism gives Oklahoma and Arkansas more opportunity to turn a blind eye to manure runoff and other untreated pollution in waterways covered by the Waters of the United States rule.

Similarly, though the U.S. Geological Survey has linked oil and gas hydraulic fracturing drilling to groundwater and surface water pollution, Oklahoma has yet to identify whether its surface waters face pollution threats from fracking activity. J.D. Strong, executive director of the Oklahoma Water Resources Board said that Oklahoma does not have the budget for widespread testing in the state.

These same challenges can be found in states across the country.

North Carolina has a long history of water pollution from coal ash spills and manure lagoons—a legacy that gained national prominence last fall when Hurricane Matthew triggered massive flooding and pollution overflows from thousands of hog farms. At the same time, contentious political battles in that state have contributed to a dramatic decrease in its environmental budget, from $126 million in 2011 to just $81 million in 2015.

Aerial Photos Document Massive Flooding of 36 Factory Farms https://t.co/jL4v1dvixx @TheCCoalition @OccupySandy

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) November 5, 2016

Even states with larger environmental budgets may struggle to protect smaller waterways under cooperative federalism because of political fights that play out at the state level.

In Kentucky, regulators and utilities are pushing to loosen regulations on the state’s coal ash ponds and landfills. Yet over the past six years, arsenic and selenium have been found to be leaching from a coal ash pond at a major power station into groundwater and directly into Herrington Lake. Despite remedial measures taken by Louisville Gas & Electric and Kentucky Utilities, the pollution persists and is poisoning fish in the lake.

In Florida, Gov. Rick Scott has gutted the state environmental agency—earning him a scathing “environmental disaster” editorial in the Tampa Bay Tribune. In addition to cutting support for clean water and conservation programs, state-driven enforcement has disappeared nearly altogether—enforcement cases fell by 81 percent from 2010 to 2015.

Pruitt’s cooperative federalism mantra, where states should see us as “partners, not adversaries,” sends us down a perilous path of continued diminishment of precious natural resources across the country.

Leaving states on their own to protect the nation’s vital water resources, without holding them to minimum standards or supporting them financially, is a slippery slope indeed towards a dirtier America—an America that the vast majority does not want.

Brooke Barton is the senior program director of Ceres’ water and food programs.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe